- 466 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Introducing the fundamentals of ethical theory, Ethics in Criminal Justice: In Search of the Truth, Seventh Edition, exposes the reader to the ways and means of making moral judgments by exploring the teachings of the great philosophers, sources of criminal justice ethics, and ethical issues in the criminal justice system.

It is presented from two perspectives: a thematic perspective that addresses ethical principles common to all components of the discipline, and an area-specific perspective that addresses the state of ethics in criminal justice in the fields of policing, corrections, and probation and parole. The seventh edition features discussion of current critical issues in criminal justice: accusations of racism, police shootings, stop and frisk policy, marijuana laws, mass incarceration, life sentences, prison privatization, the swift and certain deterrence model of probation, excessive probation fees, and the Good Lives Model in corrections. The seventh edition also offers completely revised coverage of capital punishment and the rehabilitation debate, and a discussion of how juvenile justice often fails to live up to its ideals. Finally, the book features new case studies of recent ethical dilemmas in criminal justice to enhance students' understanding of real-life ethics decision-making.

Suitable for advanced undergraduates or graduate students in criminal justice programs in the US and globally, this text offers a classical view of ethical decision-making and is well-grounded in specific case examples.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

Acquainting Yourself With Ethics

Key Terms and Definitions

- Reasoning is a pure method of thinking by which proper conclusions are reached through abstract thought processes.

- The Divided Line is Plato’s theory of knowledge. It characterizes four levels of knowledge. The lowest of these are conjecture and imagination because they are based on impressions or suppositions; the next is belief because it is constructed on the basis of faith, images, or superstition; the third is scientific knowledge because it is supported by empirical evidence, experimentation, or mathematical equations; and the highest level is reasoning.

- Theory of Realism is Aristotle’s explanation of reality. It includes three concepts: rationality, the ability to use abstract reasoning; potentiality and actuality, the “capacity to become” and the “state of being”; and the golden mean, the middle point between two extreme qualities.

- Ethics is a philosophy that examines the principles of right and wrong, good and bad.

- Morality is the practice of applying ethical principles on a regular basis.

- Intrinsic Goods are objects, actions, or qualities that are valuable in themselves.

- Nonintrinsic Goods are objects, actions, or qualities that are good only for developing or serving an intrinsic good.

- Summum Bonum is the principle of the highest good that cannot be subordinated to any other.

- E = PJ2 is the guiding formula for making moral judgment. E (the ethical decision) equals P (the principle) times J (the justification of the situation).

- Utilitarianism is the theory that identifies ethical actions as those that maximize happiness and minimize pain.

- Determinism is the theory that all thoughts, attitudes, and actions result from external forces that are beyond human control. They are fixed causal laws that control all events as well as the consequences that follow.

- Intentionalism is the theory that all rational beings possess an innate freedom of will and must be held responsible for their actions. It is the opposite of determinism.

Overview

Exhibit 1—Knowledge and Reasoning

A Life Unexamined Is Not Worth Living

Exploring Virtue

Knowledge and Virtue

The Reasoning Process

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface to the Seventh Edition

- Preface to the Sixth Edition

- Acknowledgments

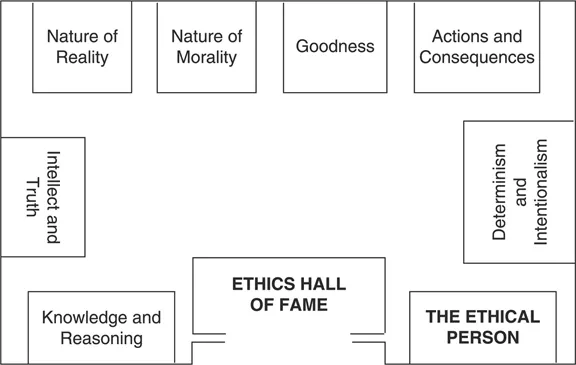

- 1. Acquainting Yourself With Ethics: A Tour of the Ethics Hall of Fame

- 2. Familiarizing Yourself With Ethics: Nature, Definitions, and Categories

- 3. Understanding Criminal Justice Ethics: Sources and Sanctions

- 4. Meeting the Masters: Ethical Theories, Concepts, and Issues

- 5. The Ambivalent Reality: Major Unethical hemes in Criminal Justice Management

- 6. Lying and Deception in Criminal Justice

- 7. Racial Prejudice and Racial Discrimination

- 8. Egoism and the Abuse of Authority

- 9. Misguided Loyalties: To Whom, to What, at What Price?

- 10. Ethics of Criminal Justice Today: What Is Being Done and What Can Be Done?

- 11. Ethics and Police

- 12. Ethics and Corrections (Prisons)

- 13. Ethics of Probation and Parole

- 14. The Truth Revealed: Enlightenment and Practical Civility Minimize Criminality

- Name Index

- Subject Index