- 350 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 4 Dec |Learn more

Understanding Syntax

About this book

Assuming no prior grammatical knowledge, Understanding Syntax explains and illustrates the major concepts, categories and terminology involved in the study of cross-linguistic syntax. Taking a theory-neutral and descriptive viewpoint throughout, this book:

-

- introduces syntactic typology, syntactic description and the major typological categories found in the languages of the world;

-

- clarifies with examples grammatical constructions and relationships between words in a clause, including word classes and their syntactic properties; grammatical relations such as subject and object; case and agreement processes; passives; questions and relative clauses;

-

- features in-text and chapter-end exercises to extend the reader's knowledge of syntactic concepts and argumentation, drawing on data from over 100 languages;

-

- highlights the principles involved in writing a brief syntactic sketch of language.

This fifth edition has been revised and updated to include extended exercises in all chapters, updated further readings, and more extensive checklists for students. Accompanying e-resources have also been updated to include hints for instructors and additional links to further reading.

Understanding Syntax is an essential textbook for students studying the description of language, cross-linguistic syntax, language typology and linguistic fieldwork.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Understanding Syntax by Maggie Tallerman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

What is syntax?

1.1 SOME CONCEPTS AND MISCONCEPTIONS

1.1.1 What is the study of syntax about?

This book is about the property of human language known as syntax. ‘Syntax’ means ‘sentence construction’: how words group together to make phrases and sentences. Some people also use the term GRAMMAR to mean the same as syntax, although most linguists follow the more recent practice whereby the grammar of a language includes all of its organizing principles: information about the sound system, about the form of words, how we adjust language according to context, and so on; syntax is only one part of this grammar.

The term ‘syntax’ is also used to mean the study of the syntactic properties of languages. In this sense it’s used in the same way as we use ‘stylistics’ to mean the study of literary style. We’re going to be studying how languages organize their syntax, so the scope of our study includes the classification of words, the order of words in phrases and sentences, the structure of phrases and sentences, and the different sentence constructions that languages use. We’ll be looking at examples of sentence structure from many different languages in this book, some related to English and others not. All languages have syntax, though that syntax may look radically different from that of English. My aim is to help you understand the way syntax works in languages, and to introduce the most important syntactic concepts and technical terms which you’ll need in order to see how syntax works in the world’s languages. We’ll encounter many grammatical terms, including ‘noun’, ‘verb’, ‘preposition’, ‘relative clause’, ‘subject’, ‘nominative’, ‘agreement’ and ‘passive’. I don’t expect you to know the meanings of any of these in advance. Oft en, terms are not formally defined when they are used for the first time, but they are illustrated so you can understand the concept, in preparation for a fuller discussion later on.

More complex terms and concepts (such as ‘case’ and ‘agreement’) are discussed more than once, and a picture of their meaning is built up over several chapters. A glossary at the end of the book provides definitions of important grammatical terms.

To help you understand what the study of syntax is about, we first need to discuss some things it isn’t about. When you read that ‘syntax’ is part of ‘grammar’, you may have certain impressions which differ from the aims of this book. So first, although we will be talking about grammar, this is not a DESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR of English or any other language. Such books are certainly available, but they usually aim to catalogue the regularities and peculiarities of one language rather than looking at the organizing principles of language in general. Second, I won’t be trying to improve your ‘grammar’ of English. A PRESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR (one that prescribes how the author thinks you should speak) might aim to teach you where to use who and whom; or when to say me and Ash and when to say Ash and I; it might tell you not to say different than or different to, or tell you to avoid split infinitives such as to boldly go. These things aren’t on our agenda, because they’re essentially a matter of taste – they are social, not linguistic matters.

In fact, as a linguist, my view is that if you’re a native speaker of English, no matter what your dialect, then you already know English grammar perfectly. And if you’re a native speaker of a different language, then you know the grammar of that language perfectly. By this, I don’t mean that you know (consciously) a few prescriptive rules, such as those mentioned in the last paragraph, but that you know (unconsciously) the much more impressive mental grammar of your own language – as do all its native speakers. Although we’ve all learnt this grammar, we can think of it as knowledge that we’ve never been taught, and it’s also knowledge that we can’t take out and examine. By the age of around 7, children have a fairly complete knowledge of the grammar of their native languages, and much of what happens aft er that age is learning more vocabulary. We can think of this as parallel to ‘learning’ how to walk. Children can’t be taught to walk; we all do it naturally when we’re ready, and we can’t say how we do it. Even if we come to understand exactly what muscle movements are required, and what brain circuitry is involved, we still don’t ‘know’ how we walk. Learning our native language is just the same: it happens without outside intervention and the resulting knowledge is inaccessible to us.

Here, you may object that you were taught the grammar of your native language. Perhaps you think that your parents set about teaching you it, or that you learnt it at school. But this is a misconception. All normally developing children in every culture learn their native language or languages to perfection without any formal teaching. Nothing more is required than the simple exposure to ordinary, live, human language within a society. To test whether this is true, we just need to ask if all cultures teach their children ‘grammar’. Since the answer is a resounding ‘no’, we can be sure that all children must be capable of constructing a mental grammar of their native languages without any formal instruction. Most linguists now believe that, in order to do this, human infants are born pre-programmed to learn language, in much the same way as we are pre-programmed to walk upright. All that’s needed for language to emerge is appropriate input data – hearing language (or seeing it; sign languages are full languages too) and taking part in interactions within the home and the wider society.

So if you weren’t taught the grammar of your native language, what was it you were being taught when your parents tried to get you not to say things like I ain’t done nowt wrong, or He’s more happier than what I am, or when your school teachers tried to stop you from using a preposition to end a sentence with? (Like the sentence I just wrote.) Again, consider learning to walk. Although children learn to do this perfectly without any parental instruction, their parents might not like the way the child slouches along, or scuffs the toes of their shoes on the ground. They may tell the child to stand up straight, or to stop wearing out their shoes. It’s not that the child’s way doesn’t function properly, it just doesn’t conform to someone’s idea of what is aesthetic, or classy. In just the same way, some people have the idea that certain forms of language are more beautiful, or classier, or are simply ‘correct’. But the belief that some forms of language are better than others has no linguistic basis. Since we oft en make social judgements about people based on their accent or dialect, we tend to transfer these judgements to their form of language. We may then think that some forms are undesirable, that some are ‘good’ and some ‘bad’. For a linguist, though, dialectal forms of a language don’t equate to ‘bad grammar’.

Again, you may object here that examples of NON-STANDARD English, such as those italicized in the last paragraph, or things like We done it well good, are sloppy speech, or perhaps illogical. This appeal to logic and precision makes prescriptive grammar seem to be on a higher plane than if it’s all down to social prejudice. So let’s examine the logic argument more closely, and see if it bears scrutiny. Many speakers of English are taught that ‘two negatives make a positive’, so that forms like (1) ‘really’ mean I did something wrong:

(1) I didn’t do nothing wrong.

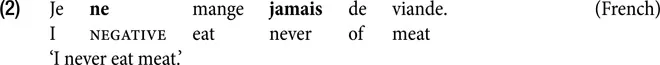

Of course, this isn’t true. First, a speaker who uses a sentence like (1) doesn’t intend it to mean I did something wrong. Neither would any of their addressees, however much they despise the double negative, understand (1) to mean I did something wrong. Second, there are languages such as French and Breton which use a double negative as STANDARD, not a dialectal form, as (2) illustrates:1

Example (2) shows that in Standard French the negative has two parts: in addition to the little negative word ne there’s another negative word jamais, ‘never’. Middle English (the English of roughly 1100 to 1500) also had a double negative. Ironically for the ‘logic’ argument, the variety of French that has the double negative is the most formal and prestigious variety, wherea...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of tables and figures

- Note to the instructor

- Note to the student

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations used in examples

- 1 What is syntax?

- 2 Words belong to different classes

- 3 Looking inside sentences

- 4 Heads and their dependents

- 5 How do we identify constituents?

- 6 Relationships within the clause

- 7 Processes that change grammatical relations

- 8 Wh-constructions: questions and relative clauses

- 9 Asking questions about syntax

- Sources of data used in examples

- Glossary

- References

- Language index

- Subject index