- 362 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Environmental Economics and Policy

About this book

Environmental Economics and Policy is a best-selling text for environmental economics courses. Offering a policy-oriented approach, it introduces economic theory, empirical fieldwork, and case studies that show how underlying economic principles provided the foundation for environmental policies.

Key features include:

- Introductions to the theory and method of environmental economics, including externalities, benefit-cost analysis, valuation methods, and ecosystem goods and services.

- Extensive coverage of the major issues including climate change mitigation and adaptation, air and water pollution, and environmental justice.

- Boxed "Examples" and "Debates" throughout the text, which highlight global examples and major talking points.

This text will be of use to undergraduate students of economics. Students will leave the course with a global perspective of how environmental economics has played and can continue to play a role in promoting fair and efficient environmental management.

The text is fully supported with end-of-chapter summaries, discussion questions, and self-test exercises in the book. Additional online resources include references, as well as PowerPoint slides for each chapter.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section II

Chapter 6

Ecosystem goods and services

Introduction

The state of ecosystem services

- Provisioning services provide direct benefits such as water, timber, food, and fiber.

- Regulating services include flood control, water quality, disease prevention, and climate.

- Supporting services consist of such foundational processes as photosynthesis, nutrient cycling, and soil formation.

- Cultural services provide recreational, aesthetic, and spiritual benefits.

- Ecosystems have changed rapidly in the last 50 years – at a rate higher than any other time period. Due to the growing demands on the earth’s resources and services, some of these high rates of change are irreversible.

- Many of the changes to ecosystems, while improving the well-being of some humans, have been at the expense of ecosystem health. Fifteen of the 24 ecosystems evaluated are in decline.

- If degradation continues, it will be difficult to achieve many of the U.N. Millennium Development Goals since resources that are vital for certain especially vulnerable groups are being affected.1 Further degradation not only intensifies current poverty, but it limits options for future generations, thereby creating intergenerational inequity.

- Finally, the Assessment suggests that reversing the degradation of ecosystems would require signifi-cant changes in institutions and policies and it specifically notes that economic instruments can play an important role in this transformation.

Economic analysis of ecosystem services

Demonstrating the value of ecosystem services

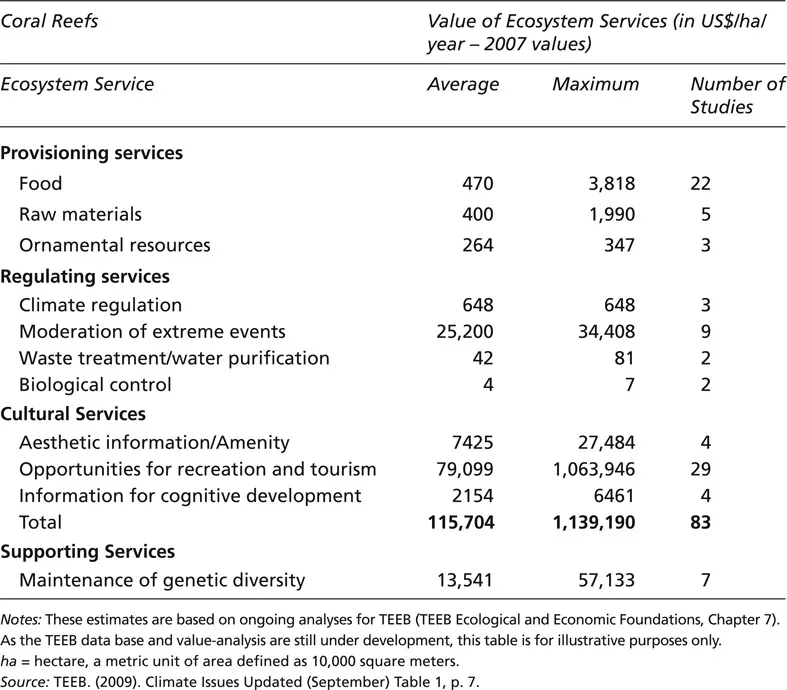

The value of reefs

- Reef related tourism – $96 million

- Recreation – $48 million

- Amenity – $35 million

- Coastal protection – $6 million

- Support to commercial fisheries – $3 million

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Brief Contents

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- An overview of the book

- Acknowledgements

- Section I Economic analysis: options and applications

- Section II Environmental policy

- Answers to self-test exercises

- Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app