eBook - ePub

Slapper and Kelly's The English Legal System

David Kelly

This is a test

Share book

- 732 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Slapper and Kelly's The English Legal System

David Kelly

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Slapper and Kelly's The English Legal System explains and critically assesses how our law is made and applied. Trusted by generations of academics and students, this authoritative textbook clearly describes the legal rules of England and Wales and their collective influence as a sociocultural institution.

This latest edition has been extensively restructured and updated, providing up-to-date and reliable analysis of recent developments that have an impact on the legal system in England and Wales.

Key learning features include:

-

- useful chapter summaries which act as a good check point for students;

-

- 'food for thought' questions at the end of each chapter to prompt critical thinking and reflection;

-

- sources for further reading and suggested websites at the end of each chapter to point students towards further learning pathways; and

-

- an online skills network including how tos, practical examples, tips, advice and interactive examples of English law in action.

Relied upon by generations of students, this book is a permanent fixture in this ever - evolving subject.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Slapper and Kelly's The English Legal System an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Slapper and Kelly's The English Legal System by David Kelly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & International Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

LAW AND LEGAL STUDY

1.1 INTRODUCTION

There are a number of possible approaches to the study of law. One such is the traditional or formalistic approach. This approach to law is posited on the existence of a discrete legal universe as the object of study. It is concerned with establishing a knowledge of the specific rules, both substantive and procedural, which derive from statute and common law and which regulate social activity. The essential point in relation to this approach is that study is restricted to the sphere of the legal without reference to the social activity to which the legal rules are applied. In the past, most traditional law courses and the majority of law textbooks adopted this ‘black letter’ approach. Their object was the provision of information on what the current rules and principles of law were, and how to use those rules and principles to solve what were, by definition, legal problems. Traditionally, English legal system courses have focused attention on the institutions of the law, predominantly the courts, in which legal rules and principles are put into operation, and here too the underlying assumption has been as to the closed nature of the legal world – its distinctiveness and separateness from normal everyday activity. This book continues that tradition to a degree, but also recognises, and has tried to accommodate, the dissatisfaction with such an approach that has been increasingly evident among law teachers and examiners in this area. To that end, the authors have not simply tried to produce a purely expository text but have attempted to introduce an element of critical awareness and assessment into the areas considered. Potential examination candidates should appreciate that it is just such critical, analytical thought that distinguishes the good student from the mundane one.

Additionally, however, this book goes further than traditional texts on the English legal system by directly questioning the claims to distinctiveness made by, and on behalf of, the legal system and considering law as a socio-political institution. It is the view of the authors that the legal system cannot be studied without a consideration of the values that law reflects and supports, and again, students should be aware that it is in such areas that the truly first-class students demonstrate their awareness and ability.

1.2 THE NATURE OF LAW

One of the most obvious and most central characteristics of all societies is that they must possess some degree of order to permit the members to interact over a sustained period of time. Different societies, however, have different forms of order. Some societies are highly regimented with strictly enforced social rules, whereas others continue to function in what outsiders might consider a very unstructured manner with apparently few strict rules being enforced (see Roberts 1979).

Order is therefore necessary, but the form through which order is maintained is certainly not universal, as many anthropological studies have shown (see Mansell 2015).

In our society, law plays an important part in the creation and maintenance of social order. We must be aware, however, that law as we know it is not the only means of creating order. Even in our society, order is not solely dependent on law, but also involves questions of a more general moral and political character. This book is not concerned with providing a general explanation of the form of order. It is concerned more particularly with describing and explaining the key institutional aspects of that particular form of order that is legal order.

The most obvious way in which law contributes to the maintenance of social order is the way in which it deals with disorder or conflict. This book, therefore, is particularly concerned with the institutions and procedures, both civil and criminal, through which law operates to ensure a particular form of social order by dealing with various conflicts when they arise.

Law is a formal mechanism of social control and, as such, it is essential that the student of law be fully aware of the nature of that formal structure. There are, however, other aspects to law that are less immediately apparent, but of no less importance, such as the inescapable political nature of law. Some textbooks focus more on this particular aspect of law than others, and these differences become evident in the particular approach adopted by the authors. The approach favoured by this book is to recognise that studying the English legal system is not just about learning legal rules, but is also about considering a social institution of fundamental importance.

1.2.1 LAW AND MORALITY

There is an ongoing debate about the relationship between law and morality and as to what exactly that relationship is or should be. Should all laws accord with a moral code, and, if so, which one? Can laws be detached from moral arguments? Many of the issues in this debate are implicit in much of what follows in the text, but the authors believe that, in spite of claims to the contrary, there is no simple causal relationship of dependency or determination, either way, between morality and law. We would rather approach both morality and law as ideological, in that they are manifestations of, and seek to explain and justify, particular social and economic relationships. This essentially materialist approach, to a degree, explains the tensions between the competing ideologies of law and morality and explains why they sometimes conflict and why they change, albeit asynchronously, as underlying social relations change.

At first sight it might appear that law and morality are inextricably linked. There at least appears to be a similarity of vocabulary in that both law and morality tend to see relationships in terms of rights and duties, and much of law’s ideological justification comes from the claim that it is essentially moral. However, that is not necessarily the case and much modern law is of a highly technical nature (such as rules of evidence or procedure), dealing with issues that have very little, if any, impact on issues of morality as such. Opinions about the relationship between law and morality diverge between two schools of thought:

- one side adopts a ‘natural law’ approach, which claims that law must be moral in order to be law, and that ‘immoral law’ is a contradiction in terms. Natural lawyers usually base their ideas of law on underlying religious beliefs and texts which are in the very literal sense sacrosanct, but this is not a necessity and opposition to specific law may be based on pure reason or political ideas.

- The other side can be characterised as ‘legal positivists’. They argue that law has no necessary basis in morality and that it is simply impossible to assess law in terms of morality.

These issues feed into debates as to what is connoted by the rule of law, which will be considered in some detail in Chapter 2 of this text.

The legal enforcement of morality: the Hart v Devlin debate

This aspect of the law and morality debate may be reduced to the question: does the law have a responsibility to enforce a moral code, even where the alleged immorality takes place in private between consenting adults? Consider this example: in Britain there are over two million cohabiting gay couples. Homosexual sex was legalised in 1967 (for 21-year-olds, lowered to 18-year-olds in 1994), and consensual heterosexual anal intercourse was decriminalised by s 143 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994. In British legal debate the moral issue was fought out in the 1960s by Lord Devlin and Professor HLA Hart. Devlin argued that ‘the suppression of vice is as much the law’s business as the suppression of subversive activities’. A shared morality, he argued, is the cement of society, without which there would be aggregates of individuals but no society. Hart argued that people should not be forced to adopt one morality for its own sake. He repudiated the claim that the loosening of moral bonds is the first stage of social disintegration, saying that there was no more evidence for that proposition than there was for Emperor Justinian’s statement that homosexuality was the cause of earthquakes.

In any event it might be said that Hart ‘won’ the debate in the sense that it was his influence that led to the passing of the 1960s legislation liberalising the law on abortion, prostitution and homosexuality, and abolishing capital punishment. However, such issues can still arise – as was seen in the Brown case, considered later, and the ongoing issue of the ‘rights’ relating to assisted suicide as considered in R (on the application of Purdy) v Director of Public Prosecutions (2009).

The morality of the lawmaker

One particular aspect of the debate that will be repeatedly highlighted in what follows is the way in which certain individuals, particularly judges, have the power not just to make and mould law, but to make and mould law in line with their own ideologies, i.e. their individual values, attitudes and prejudices – in other words, their moralities.

Morality vis à vis the law constitutes an external environment which interacts with the lawmaking process, not because law makers are blessed with divine insight into the ‘general will’, but rather because laws tend to be based on value – loaded information which percolates to the law-makers (whose own individual values have a disproportionate influence upon the process) (L Blom-Cooper and G Drewry, Law and Morality (1976), p xiv).

This issue is central to the Royal College of Nursing case considered in Chapter 3 and on the Companion Website at: www.routledge.com/cw/slapper.

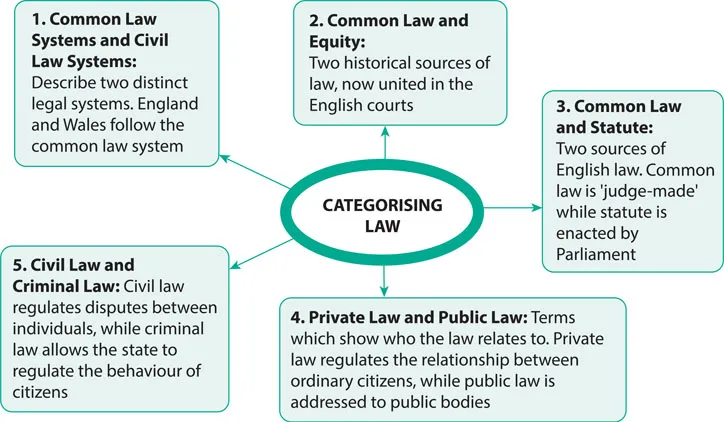

1.3 CATEGORIES OF LAW

There are various ways of categorising law, which initially tend to confuse the non-lawyer and the new student of law. What follows will set out these categorisations in their usual dual form, while at the same time trying to overcome the confusion inherent in such duality. It is impossible to avoid the confusing repetition of the same terms to mean different things and, indeed, the purpose of this section is to make sure that students are aware of the fact that the same words can have different meanings, depending upon the context in which they are used.

1.3.1 COMMON LAW AND CIVIL LAW

In this particular juxtaposition, these terms are used to distinguish two distinct legal systems and approaches to law. The use of the term ‘common law’ in this context refers to all those legal systems that have adopted the historic English legal system. Foremost among these is, of course, the United States, but many other Commonwealth and former Commonwealth countries retain a common law system. The term ‘civil law’ refers to those other jurisdictions that have adopted the European continental system of law derived essentially from ancient Roman law, but owing much to the Germanic tradition.

The usual distinction to be made between the two systems is that the common law system tends to be case-centred and hence judge-centred, allowing scope for a discretionary, ad hoc, pragmatic approach to the particular problems that appear before the courts, whereas the civil law system tends to be a codified body of general abstract principles which control the exercise of judicial discretion. In reality, both of these views are extremes, with the former overemphasising the extent to which the common law judge can impose their discretion and the latter underestimating the extent to which continental judges have the power to exercise judicial discretion. It is perhaps worth mentioning at this point that the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), established, in theory, on civil law principles, is in practice increasingly recognising the benefits of establishing a body of case law.

FIGURE 1.1 Categorising law

It has to be recognised, and indeed the English courts do so, that, although the CJEU is not bound by the operation of the doctrine of stare decisis (see 4.2), it still does not decide individual cases on an ad hoc basis and, therefore, in the light of a perfectly clear decision of the CJEU, national courts will be reluctant to refer similar cases to its jurisdiction. Thus, after the ECJ, as it was then referred to, decided in Grant v South West Trains Ltd (1998) that Community law, now referred to as Union law, did not cover discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation, the High Court withdrew a similar reference in R v Secretary of State for Defence ex p Perkins (No 2) (1998) (see 5.3 for a detailed consideration of the CJEU).

1.3.2 COMMON LAW AND EQUITY

In this particular juxtaposition, the terms refer to a particular division within the English legal system.

The common law has been romantically and inaccurately described as the law of the common people of England. In fact, the common law emerged as the product of a particular struggle for political power. Prior to the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, there was no unitary, national legal system. The emergence of the common law represents the imposition of such a unitary system under the auspices and control of a centralised power in the form of a sovereign king; in that respect, it represented the assertion and affirmation of that central sovereign power.

Traditionally, much play is made about the circuit of judges travelling round the country establishing the...