Essentials of Economics in Context

Neva Goodwin, Jonathan M. Harris, Pratistha Joshi Rajkarnikar, Brian Roach, Tim B. Thornton

- 600 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Essentials of Economics in Context

Neva Goodwin, Jonathan M. Harris, Pratistha Joshi Rajkarnikar, Brian Roach, Tim B. Thornton

About This Book

Essentials of Economics in Context is specifically designed to meet the requirements of a one-semester introductory economics course that provides coverage of both microeconomic and macroeconomic foundations. It addresses current economic challenges, paying specific attention to issues of inequality, globalization, unpaid work, technology, financialization, and the environment, making the text a genuinely twenty-first century introduction to economics.

Aspects of history, institutions, gender, ethics, and ecology are integrated throughout the text, and economic analysis is presented within broader themes of human well-being, and social and environmental sustainability. Theoretical expositions in the text are kept close to reality by integrating numerous real-world examples and by presenting the material in the recognized accessible and engaging style of this experienced author team.

Key features of Essentials of Economics in Context include:

• an inclusive approach to economics, where the economy is analyzed within its social and environmental context

• an innovative chapter examining data on various economic indicators

• focus on goals of human well-being, stability, and sustainability, and inclusion of core and public

purpose spheres, instead of solely focusing on market activities

- a wealth of online materials such as slides, test banks, and answers to exercises in the book

This text is the ideal resource for one-semester introductory economics courses globally.

The book's companion website is available at: http://www.bu.edu/eci/education-materials/textbooks/essentials-of-economics-in-context/

Frequently asked questions

Information

Part I

The Context for Economic Analysis

Chapter 0

Economics and Well-Being

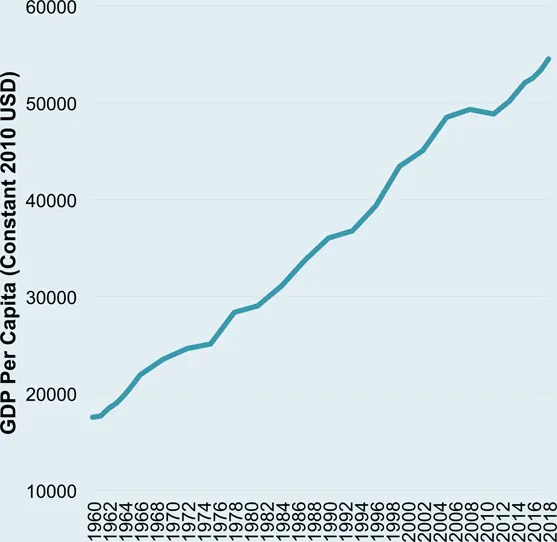

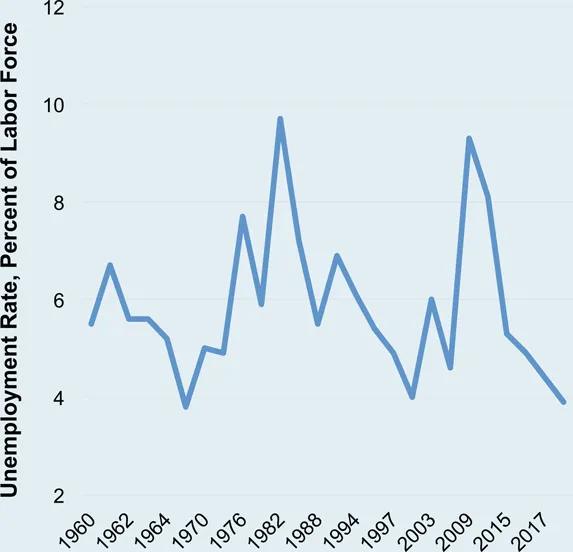

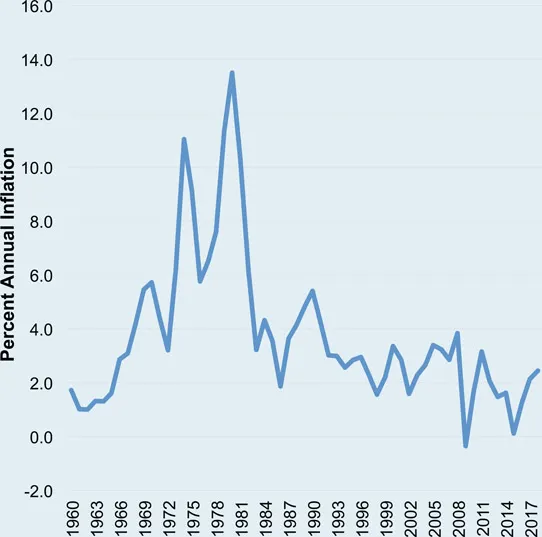

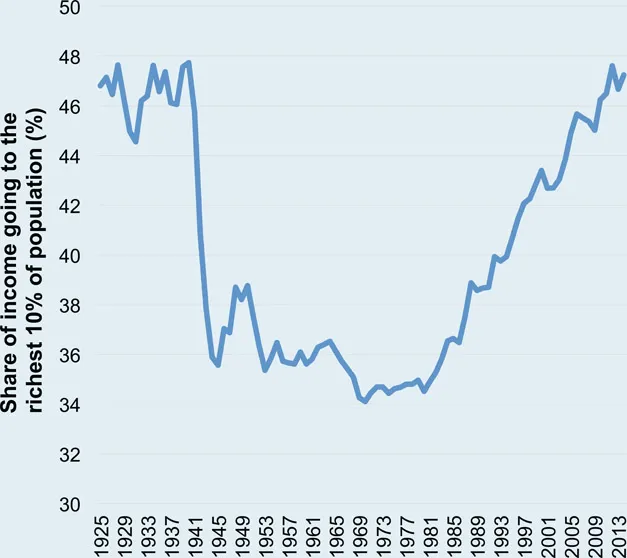

- Time trends graphs presenting time-series data that show how a particular variable changes over time; and

- Bar graphs presenting cross-sectional data that show observations on a particular variable for many subjects (such as individuals, firms, countries, or regions) at one point in time. In this chapter, we look at cross-sectional data for different countries to make international comparisons on specific economic variables, but you will see similar graphs comparing individuals or firms at several points in the book. While we mainly focus on the United States here, and in much of the rest of the book, it is important to see individual country data within the global context. If you are interested in the performance of specific countries we have not included here, detailed tables are available on the book’s companion website: www.bu.edu/eci.

Time Trend Graphs

- U.S. GDP per Capita

- U.S. Unemployment Rate

- U.S. Inflation Rate

- U.S. Income Inequality

- Gender-Based Earnings Inequality

- Global International Trade

- Global Carbon Dioxide Emissions

Bar Graphs: International Comparisons

- GDP per Capita

- Unemployment Rate

- Inflation Rate

- Trade Balance

- Income Inequality

- Absolute Poverty

- Educational Performance

- Life Expectancy

- Carbon Dioxide Emissions per Capita