Project Management for Engineering, Business and Technology

- 732 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Project Management for Engineering, Business and Technology

About this book

Project Management for Engineering, Business and Technology is a highly regarded textbook that addresses project management across all industries. First covering the essential background, from origins and philosophy to methodology, the bulk of the book is dedicated to concepts and techniques for practical application. Coverage includes project initiation and proposals, scope and task definition, scheduling, budgeting, risk analysis, control, project selection and portfolio management, program management, project organization, and all-important "people" aspects—project leadership, team building, conflict resolution, and stress management.

The systems development cycle is used as a framework to discuss project management in a variety of situations, making this the go-to book for managing virtually any kind of project, program, or task force. The authors focus on the ultimate purpose of project management—to unify and integrate the interests, resources and work efforts of many stakeholders, as well as the planning, scheduling, and budgeting needed to accomplish overall project goals.

This sixth edition features:

-

- updates throughout to cover the latest developments in project management methodologies;

-

- a new chapter on project procurement management and contracts;

-

- an expansion of case study coverage throughout, including those on the topic of sustainability and climate change, as well as cases and examples from across the globe, including India, Africa, Asia, and Australia; and

-

- extensive instructor support materials, including an instructor's manual, PowerPoint slides, answers to chapter review questions and a test bank of questions.

Taking a technical yet accessible approach, this book is an ideal resource and reference for all advanced undergraduate and graduate students in project management courses, as well as for practicing project managers across all industry sectors.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part I

Philosophy and concepts

Chapter 1

What is project management?

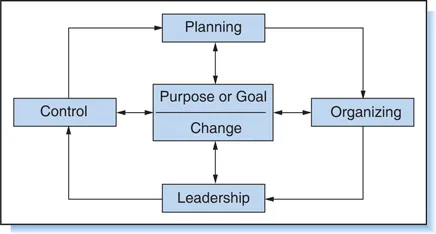

1.1 Functions of management1

The functions of management.

1.2 Features of project management

1.3 Evolution of project management

Chapters 6 and 7 No single individual or industry can be credited with the idea of project management. It is often associated with the early US missile and space programs of the 1960s, but clearly its origins go back much earlier. Techniques of project management probably were first used in the major construction works of antiquity, such as the Pyramids and the Roman aqueducts, and were later modified for use on other projects such as shipbuilding. Starting in the early twentieth century, managers developed techniques for use in other kinds of projects, such as for designing and testing new products and building and installing specialized machinery. During World War I, a new tool called the Gantt chart for scheduling and tracking project-type work was developed (examples in Chapter 6), followed about 40 years later by the project network diagram (discussed in Chapter 7).

Chapters 7 and 8By the 1950s, the size and complexity of many projects had increased so much that existing management techniques proved inadequate. Repeatedly, large-scale projects for developing aircraft, missiles, communication systems, and naval vessels suffered enormous cost and schedule overruns. To grapple with the problem, two new methods for planning and control were developed, one called PERT, the other called CPM (described in Chapters 7 and 8). A decade later, network-based methods were refined to integrate project cost accounting with project scheduling. These methods came into widespread usage in the 1960s when the US government mandated their usage in projects for the Department of Defense, NASA, and large-scale efforts such as nuclear power plants. In the 1970s, the earned value method of project tracking was developed (see Chapter 13); this led to performance measurement systems that simultaneously track work expenditures and work progress.

Chapter 13 The last 50 years have witnessed the increased computerization of project management. Early project planning and tracking systems cost $10,000 to $100,000, but today relatively low-cost software and freeware make possible the use of a variety of planning, scheduling, costing, and controlling tools for virtually any size project.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Brief Contents

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About the authors

- Introduction

- PART I: PHILOSOPHY AND CONCEPTS

- PART II: SYSTEMS DEVELOPMENT AND PROJECT LIFE CYCLE

- PART III: SYSTEMS AND PROCEDURES FOR PLANNING AND CONTROL

- PART IV: ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR

- PART V: PROJECT MANAGEMENT IN THE CORPORATE CONTEXT

- Appendix A: Request for proposal for Midwest Parcel Distribution Company

- Appendix B: Proposal for Logistical Online System Project

- Appendix C: Project execution plan for logistical online system

- Index