- 572 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Focusing on sites of key significance and the world's first civilizations, Ancient Lives is an accessible and engaging textbook which introduces complete beginners to the fascinating worlds of archaeology and prehistory.

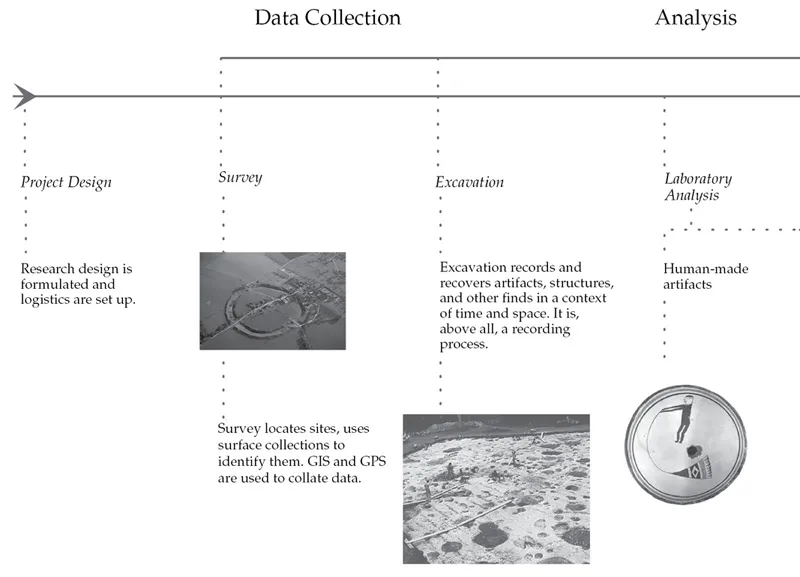

Drawing on their impressive combined experience of the field and the classroom, the authors use a jargon-free narrative style to enliven the major developments of more than 3 million years of human culture. First introducing the basic principles, methods, and theoretical approaches of archaeology, the book then provides a summary of world prehistory from a global perspective. This latest edition provides an up-to-date account of human evolution and the origins of modern humans. It explores the reality of life in the prehistoric world. Later chapters describe the development of agriculture and animal domestication, and the emergence of cities, states, and preindustrial civilizations in widely separated parts of the world. Our knowledge of these is changing thanks to revolutionary developments in LIDAR (light detection and ranging) technology and other remote-sensing devices.

With this new edition updated to reflect the latest discoveries and research in the discipline, Ancient Lives continues to be a comprehensive and essential introduction to archaeology. It will be ideal for students looking for an accessible guide to the subject.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1Introducing Archaeology and Prehistory

Chapter Outline

How Archaeology Began

Lost Civilizations

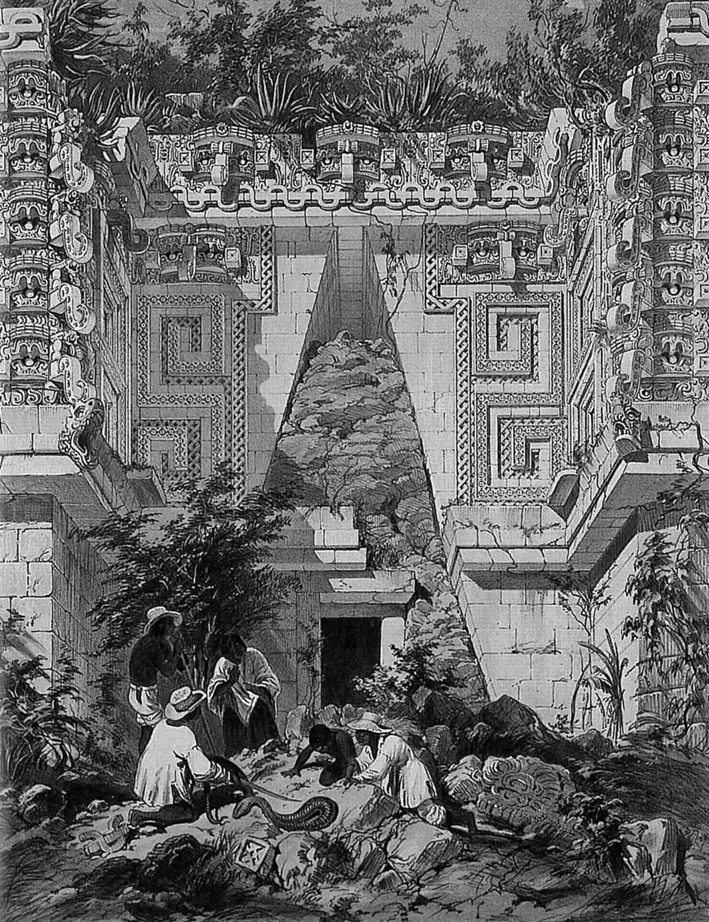

Stephens, Catherwood, and Maya Copán

But How Old Was Humanity?

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Brief Contents

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Author Notes

- Part I Archaeology: Studying Ancient Times

- Part II Ancient Interactions

- Part III The World of the First Humans

- Part IV Modern Humans Settle the World

- Part V The First Farmers and Civilizations

- Part VI The Ancient Americas

- Part VII Finale

- Glossary

- References

- Index