Worldwide Destinations

The Geography of Travel and Tourism

Brian Boniface, Chris Cooper, Robyn Cooper

- 732 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Worldwide Destinations

The Geography of Travel and Tourism

Brian Boniface, Chris Cooper, Robyn Cooper

About This Book

Worldwide Destinations: The Geography of Travel and Tourism is a unique text that explores tourism demand, supply, organisation and resources for every country worldwide. The eighth edition is brought up to date with features such as:

-

- An exploration of current issues such as climate change, overtourism, expedition cruises, film tourism, economic and cultural impacts of tourism.

-

- New and updated case studies throughout.

-

- More emphasis on South-east Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

-

- Online resources for lecturers and students including PPTs, web links, video links and meditations on the evolving implications of COVID-19 for tourism.

The first part of the book comprises thematic chapters which detail the geographic knowledge and principles required to analyse the tourism appeal of destinations. The subsequent division of the book into regional chapters enables the student to carry out a systematic analysis of a particular destination, by providing insights on cultural characteristics as well as information on specific places.

Worldwide Destinations: The Geography of Travel and Tourism is an invaluable resource for studying every destination in the world, by explaining tourism demand, evaluating the many types of tourist attractions and examining the trends that may shape the future geography of tourism. This thorough guide is a must-have for any student undertaking a course in travel and tourism.

Frequently asked questions

Information

PART I The geographical principles of travel and tourism

1 An introduction to the geography of travel and tourism

- Define and use the terms leisure, recreation and tourism and understand their interrelationships

- Distinguish between tourism, migration and other types of mobility

- Distinguish between the different forms of tourism, and the relationship of different types of tourist with the environment

- Appreciate the importance of scale in explaining patterns of tourism

- Identify the three major components of the tourism system

- Explain the push and pull factors that give rise to tourist flows

- Appreciate the methods used to measure tourist flows and be aware of their shortcomings.

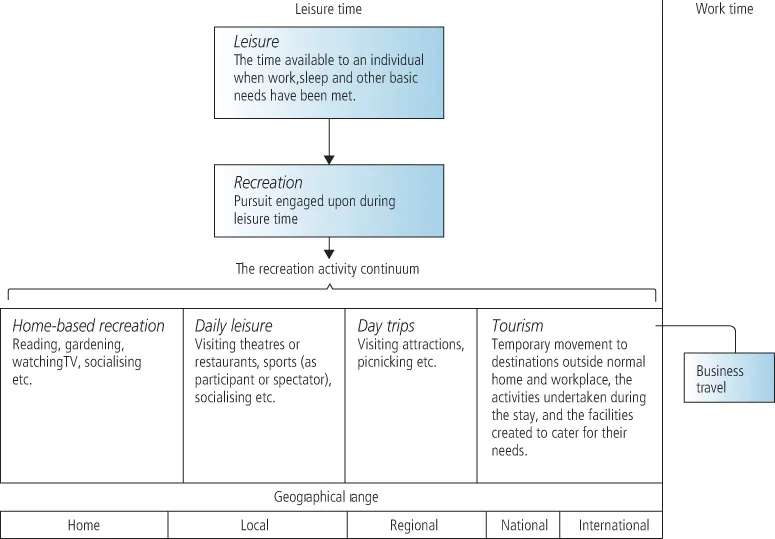

Leisure, recreation and tourism

Leisure, recreation and tourism.

- First, the approach puts movement centre-stage and increases our understanding of the underlying processes driving patterns of tourism movement. The key question is to understand and explain what influences these movements, from personal resources at a micro scale to geo-politics at a macro scale.

- Second, mobilities blur the distinction between home, work and tourist destinations, and between differing types of traveller – whether they are commuters, shoppers or migrants. This makes reconciling the ‘mobilities’ approach with drawing up ‘definitions’ of tourism problematic – particularly when we go back to the definitions of tourism designed by the UNWTO which we deal with below.

- Not everyone can be part of this world of movement. To travel involves mustering the personal resources needed and yet some argue that the mobilities approach ignores these inequalities. Only 2 or 3 per cent of the world’s population engage in international tourism, and some that do are ‘hypermobile’ engaging in many trips in any one year.

- Much of this world of movement is also involuntary. In addition to refugees fleeing political or religious discrimination, there are economic migrants seeking a better life, and a modern form of the slave trade – women and children trafficked to provide unpaid labour or forced into prostitution.

- First we can define tourism from the demand side, i.e. the person who is the tourist. This approach is well developed and the United Nations Statistical Commission now accepts the following definition of tourism: ‘The activities of persons travelling to and staying in places outside their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business and other purposes’. This definition raises a number of issues:

- What is a person’s usual environment?

- The inclusion of ‘business’ and ‘other’ purposes of visit demands that we conceive of tourism more widely than simply as a recreational pursuit.

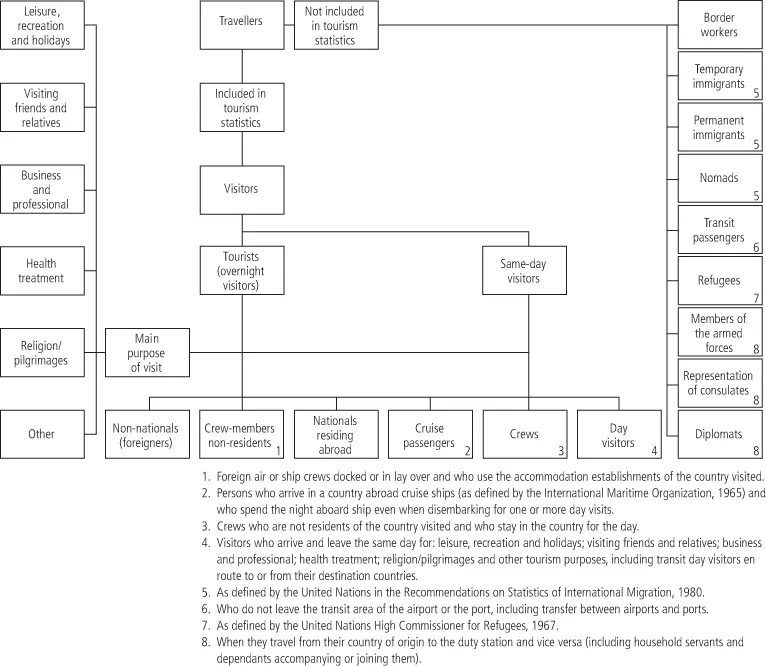

- Certain types of traveller are excluded from the definition. Tourism is only one part of the spectrum of travel, which ranges from the daily journey to work, or for shopping, to migration, where the traveller intends to take up permanent or long-term residence in another area (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2

Classification of travellers.

- We can also define the tourism sector from the supply-side point of view. Here the difficulty lies in disentangling tourism businesses and jobs from the rest of the economy. After years of debate, the accepted approach is the tourism satellite account (TSA), adopted by the United Nations in 2000. The TSA measures the demand for goods and services generated by visitors to a de...