A temporary endeavour undertaken to create a unique product or service or result.

The business of bringing together people and resources to achieve a one-off purpose (such as building a pyramid) has been one of the defining features of human society for as long as we can imagine. However, project management tools first emerged in engineering in the early 1900s, with the projects simply being managed by the architects, engineers and builders themselves. From the 1950s, project management tools and techniques were systematically applied to engineering and spread to other fields, such as construction and defence activity (Cleland & Gareis 2006). Since then, the rapid development of modern project management has seen it recognised as a distinct discipline, with two major worldwide professional organisations: the International Project Management Association (IPMA), established in 1967, and the Project Management Institute (PMI), in 1969. The PMI publishes a popular project management guidebook—A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide)—and it specifies projects more formally as:

Projects are undertaken to fulfil objectives by producing deliverables. An objective is defined as an outcome toward which work is to be directed, a strategic position to be attained, a purpose to be achieved, a result to be obtained, a product to be produced, or a service to be performed. A deliverable is defined as any unique and verifiable product, result, or capability to perform a service that is required to be produced to complete a process, phase, or project.

(PMI 2017, p. 4)

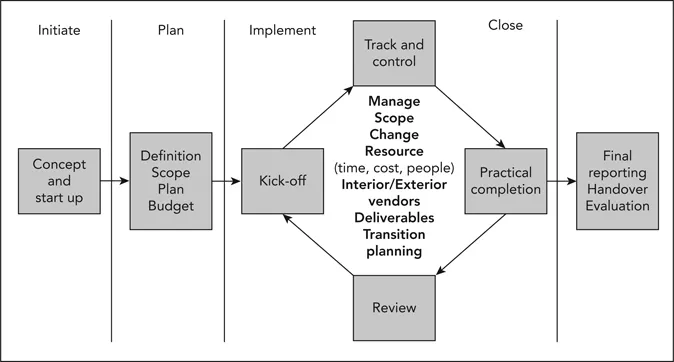

The temporary nature of a project indicates a definite beginning and end. The end is reached when the project’s objectives have been achieved or when the project is terminated because its objectives will not or cannot be met, or because the need for the project no longer exists. However, projects can have social, economic and environmental impacts that far outlast their end dates.

In the past twenty years, we have seen increasing attention given to projects in health and community services, with project management being recognised as one of the required competencies for health care managers (Sie & Liang 2015). As a result, most postgraduate courses in health care management, public health and health promotion incorporate project management competencies into the curriculum.

Although each project is unique, they all have some common characteristics. By definition, they are one-off efforts to achieve a goal, with a beginning and end as well as a budget/resources. They also have a common life cycle; have defined deliverables that are achieved and can be measured during or at the end of the project; and may enable changes that transform processes, performance and culture (Newton 2012; Roberts 2011; Turner 2007). Projects are also opportunities to create new knowledge and techniques to improve practice.

Projects have several characteristics that can make them challenging. First, each project is a unique and novel endeavour (Olsen 1971; Westland 2006), so, by definition, it hasn’t been done before. This is one of the reasons why the original project design is often modified during project implementation, and why monitoring to identify and respond to early warning signs is often critical to project success. Second, depending on its size, the project may also require the involvement of many different occupational groups, different parts of the organisation, and different functions and resources, and these must be brought together to focus on the achievement of the objectives of the project. Team dynamics can also be critical when a wide range of roles, skills and expertise is required by the project.

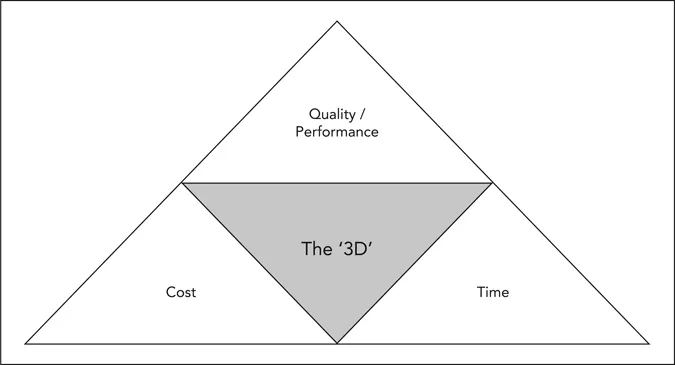

Third, the targets set by a project are often complex and can require levels of technical performance not yet generally achieved in the field (Olsen 1971; Westland 2006). Complexity can arise from the different perspectives of various disciplines involved, the inexperience of the players, the number of interested parties, the geographic spread, the quantum of change, technical/solution complexity and so on. For example, hospital redevelopment projects are typically very complex undertakings involving constructing a new facility (often on an existing site), introducing new technology and procedures, and changing the size and structure of the staff, while also continuing to offer services. In a project such as this, important stakeholders may be opposed to one another, different departments with different agendas will be participating and political involvement will be high. All of these factors can have an impact on decision-making, the project scope, the communication challenge and the chances of success or failure.

Fourth, managing a project also means managing a dynamic situation, as the unexpected is always happening (Cleland & King 2008). When a new problem arises, it must be addressed immediately, because the project is limited by its timelines. Changes and modifications may add significant costs to the project budget. For example, it is expensive to change the spec-ifications of a new Information and Communication Technology system once design work is underway. It can be expensive in a different way to change the goals or scope of an organisational restructuring project. Senior management can dictate a change of direction to respond to changes in the internal or external environments, but doing so is likely to damage commitment and goodwill among those affected, who often value certainty.

Projects can vary in scope from something as simple as implementing the use of a new type of catheter to a complex undertaking such as introducing a new model of care. Projects may impact and be visible to the whole organisation and wider community—glamorous and exciting—or they may be hidden away in a small team or department—committed people doing good work.

Managing projects can be similar to managing high-risk businesses (Chen 2011; Westland 2006). Projects are often used to trial new ideas, so there is a lot of uncertainty and some unknowns. For large projects, estimation of time and cost can be more an art than a science, based more on the experience of the project manager than sophisticated modelling. Projects can also be at risk from external factors such as stakeholder resistance, political intervention, changes of policy direction and funding cuts.