- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

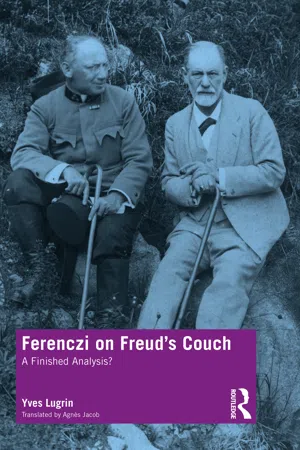

This fascinating book assesses Sándor Ferenczi's role in the history of psychoanalysis, examining his personal analysis with Freud, the father of the discipline.

The book delves into archival material to shed light on issues around transference between Freud and Ferenczi, as well as Ferenczi's own development as "the first analyst." It offers a unique deciphering of the transmission of psychoanalysis, distinguishing between self-analysis, personal analysis and training analysis, including a discussion on the duration and end of treatment, subjects rarely discussed in contemporary circles.

This book is an important read for practising clinicians and scholars alike.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ferenczi on Freud’s Couch by Yves Lugrin, Agnès Jacob in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicologia & Terapia cognitivo-comportamentale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Before the actual request for analysis (1908–1912)

Teaching, love and trembling (1908–1909)

In 1909, at the end of the summer, Freud and Jung sail for New York; they have been invited by James J. Putnam to lecture at Clark University in Worcester. Freud has asked Ferenczi to join them. Each morning, while the two of them stroll in the countryside, Freud prepares the lecture he will give that afternoon. The two men grow closer. Freud’s letter dated October 6, 1909, opens for the first time with “Dear friend,” instead of “Dear Doctor” or “Esteemed colleague.” Freud did not bestow such marks of friendship easily. On October 22, Freud confides to Ferenczi, for whom clinical work is a veritable passion, that he doesn’t feel the same way: “The patients are disgusting and are giving me an opportunity for new studies on technique.” On October 30, in response to Freud’s request that Ferenczi promote the teaching of psychoanalysis, Ferenczi’s letter expresses satisfaction with what has been accomplished over the past 20 months. “Do not be frightened by my talkativeness; I only want to remain true to the tradition of reporting on the progress of my apostolic mission on the basis of fresh impressions.” And he reports on his performance: “So, today was the lecture about ‘Everyday Life.’ I was happy that I could speak before approximately three hundred young and enthusiastic medical students, who listened to my (or, that is to say, your) words with bated breath.” The two men have grown so close that when Ferenczi gives lectures on psychoanalysis, it might as well be Freud speaking. Well-versed in self-analysis, Ferenczi adds a few words in parentheses on a matter that he senses may become problematic between them: “(N.B.: I have already determined that it has to do with the infantile wish to be praised by the father.)”

Ferenczi perfectly understands the effect of the transference which develops in a relation of shared work and a common cause, when there is also friendship involved, and even a father/son relation: Freud often places his colleague (17 years his junior) in the generation of his children. He can envisage Ferenczi marrying his daughter, and invites him to hike in the mountains with his sons. In the correspondence, Ferenczi relies increasingly on their transferential relation to discuss his personal life – that of a 37-year-old bachelor. Freud becomes the one from whom he seeks support for, and to whom he addresses, his self-analysis; this analysis becomes part of the content of the letters, along with the exchange of ideas, and information about the progress of the movement. Moreover, as early as the summer of 1908, Freud points out to the man he now regards as a potential successor that he is at a disadvantage for someone who will soon have to bear responsibility for the emerging psychoanalytic movement, because at 37 he is still unmarried and has no children – nor would he have any later – while at the same age Freud was a married man and the father of five children. This was another considerable difference between the psychic structure of the two men. Shortly after their trip to America, as they grew closer, Ferenczi was very willing to discuss this problem. In fact, at first, it was unclear which of the two men considered it more troublesome. Their relationship would soon become more complicated and take another direction which we see as having led to the request for analysis.

Chercher la femme (winter 1910)

On October 26 and 30, 1909, Ferenczi first mentions the existence of a woman with whom he is not yet living (she would become his wife ten years later). On October 16, he first refers to her in a letter, under an eloquent alias:

My personal well being (psychic) was good right up to the last few day as long as it was possible to keep frequent company with Frau Isolde (I will call her that, which was also her name in one of my dreams).

The drama involved in their love story was, however, more prosaic than the grandiose tragedy of Tristan and Iseult: “The difficult and painful operation of producing complete candor in me and in my relationship with her is proceeding rapidly.” In his own past, Freud had to rely on self-analysis at points of crisis in his troubled relations with Fliess, and in his ambivalent relation to his father, Jakob Freud, an old man who had been married three times and was by then on the threshold of death. But Ferenczi was going to request analysis when the unclear aspects of his relationship with women, his sexual relationship with them, brutally intruded into his analytic practice. Now, in the autumn of 1909, he was not yet ready to take this step. Both Ferenczi and his partner looked to psychoanalysis to provide answers that would resolve the predicament of their relationship. Ferenczi thought that Frau Isolde could find there the strength “to allow the […] resistances to be overcome and the bitterness of the unvarnished truth to be accepted […]” As for familiarity with, and overindulgence in, self-analysis: “The matter, of course, makes much more rapid progress in me; I dream a great deal, analyze my dreams, and find lots of infantilisms.” He tells Freud that after a recent discussion with Frau Isolde, he was able to identify the tormenting difficulty in their relation:

I must say that the confession that I made to her, the superiority with which, after some reluctance, she correctly grasped the situation, and the truth which is possible between us makes it seem perhaps less possible for me to tie myself to another woman in the long run, even though I admitted to her and to myself having sexual desires toward other women and even reproached her for her age.

He loves this married woman, Mrs Palos, but desires her daughter. This woman, the mother of two young girls, is seven years older than Ferenczi, making the prospect of parenthood unlikely. This deeply personal difficulty, which apparently had not troubled Ferenczi until then, takes on a new dimension given his entanglement with psychoanalysis and with Freud: “Evidently I have too much in her: lover, friend, mother, and, in scientific matters, a pupil, i.e., the child – in addition, an extremely intelligent, enthusiastic pupil, who completely grasps the extent of the new knowledge.”

Towards the end of the year, Frau Isolde recovers her own humble identity: her name is Gizella. On December 3, Freud writes that he has sent to Budapest a copy of Everyday Life, “for Frau Gizella,” as promised. In his letter to Freud dated December 7, there is mention of the fact that “Frau G.” sends Freud “the enclosed lines.” Soon Freud and Frau G. were to exchange entire, important letters, and Freud learned to appreciate Gizella’s qualities. In the letter dated December 7, Ferenczi makes reference to his personal feelings: “What has happened in me and with me otherwise you will find in the enclosed ‘diary pages.’ I have made an effort to be completely honest despite the fact that I know that you will read it.” The editor of the Freud/Ferenczi correspondence observes, in a footnote, that this “enclosed” document was never found. Still, we learn that at the end of 1909 Ferenczi was already keeping a diary. Was he looking for another outlet for his feelings, so as not to overburden Freud in his letters? The latter skilfully and cautiously avoids entering into any further discussion of Ferenczi’s complicated love life. Moreover, after the start of 1910 Freud makes no more mention of the confidences Ferenczi made about his tormented personal life, so as to keep him focused on the political circumstances pertaining to psychoanalysis. Ferenczi accepts being the fighting man Freud needs in the social sphere, but does not give up hope for an open and close personal relationship with Freud, in which the most private matters could be discussed.

Trust and combat (1910–1912)

On January 1, 1910, at the end of a letter to Ferenczi, Freud asks for his advice on the institutional processes to be put in place to establish a policy for psychoanalysis: “Incidentally, what do you think of a tighter organization with formal rules and a small fee? Do you consider that advantageous? I also wrote Jung a couple of words about this.” The next day, Ferenczi’s reply is preceded by the expression to his deep gratitude to Freud. He is emphatic: “[…] you [have] enhanced the lives and occupation of a very large number of people who were previously striving in vain for recognition.” Inclined to be very enthusiastic, Ferenczi considers Freud’s followers “the predecessors of all humanity, which, for the time being, is still stuck in infantile resistances,” and he is convinced that Freud’s work “will leave behind strong traces in world history.” He insists on making one more thing clear: “I say all of this after appropriate correction, after removing everything that personal adherence, and especially my own father complex, could dictate to me. Without this correction this letter would have come out much more effusive.” Ferenczi could not have known then that the passionate tone of his remarks bore a strange resemblance to that of Freud’s own letters to his friend Wilhelm Fliess, written 15 years earlier, when he saw Fliess as a genius, “the new Kepler.”

After this declaration of love and respect, Ferenczi goes on to answer Freud, speaking as a fighting man: “I find your suggestion (tighter organization) extremely useful. The acceptance of members, however, would be just as strictly managed as it is in the Vienna Society; that would be a way of keeping out undesirable elements.” In February 1908 there had already been discussion about reshaping the functioning – admission of new members, external sites, modes of intervention – of the little group constituting the Wednesday Society, whose status was not clearly defined. Admission of new members was decided by a vote, and it was the custom that they give a presentation. The proposition to introduce stricter admission criteria was rejected. But the question of the institutionalisation of psychoanalysis, and of member selection, had been raised. This question was clearly at the forefront of Freud’s concerns regarding an international organisation entrusted with ensuring the Freudian orientation of national and local associations bound to be created in the future.

In a long post-scriptum to his letter dated January 2, 1910, Ferenczi points out the extent to which the analytic and political spheres overlap. He specifies that in his own relations with his colleagues, his “tiresome brother complex is still playing tricks on [him].” He never hid his tendency to rivalry and jealousy, surfacing whenever Freud praised one or the other of his followers. Ferenczi adds: “[…] this affect is for me the measure of the work that I still have to do on myself,” without specifying if he is referring to continuing his self-analysis, as we suspect, or to another sort of work – personal analysis – an idea taking hold in him more and more firmly. A week later, on January 10, it is Freud’s turn to proffer praise: “Analyses and writings, as you now do them, are very significant events for one’s own person, and the other – if he comes into it at all – has nothing to do but keep a respectful silence.” Freud is impressed: “I can hardly admire perspicacity, for I know that it is made up of honesty and firm decision. Certainly you are right in every instance.” We can imagine Ferenczi’s emotion when he read these words and the explanations which followed.

Chercher la femme, once again

In this letter, and after having remained silent on the subject for over two months, Freud comes back to the romantic torment Ferenczi disclosed. Freud congratulates him not only for the relevance of the analysis of one of his own dreams – an analysis recently presented to Freud in person (the dream is not included in the correspondence) – but also, and above all, for his attitude: the decision to be completely honest with Gizella. Freud adopts a new standpoint; he no longer draws Ferenczi’s attention to a problem that must be solved; instead, he becomes an active participant in the conjugal scenario beginning to unfold. At this point, he has not yet met Gizella, about whom he has an unfavourable opinion, as he would later admit. Thus, Freud approves of Ferenczi’s perilous decision not to hide from this woman the doubts he harbours about his love for her: “As to what is real, I have to say that you were by and large undoubtedly correct with your disclosure to the beloved woman.” Freud does not yet see a symptom in the fact that Ferenczi is torn between the woman he thinks he loves and all the other women he still desires. On the contrary, Freud seems to find justification for this ambivalence:

It belongs to the ABC of our word view that the sexual life of a man can be something different from that of a woman, and it is only a sign of respect when one does not conceal this from a woman.

As he would later admit to Gizella herself, when he had come to know her well, he had perhaps believed, secretly, that Ferenczi would make a mistake by becoming tied to a married woman with two daughters, who was, moreover, seven years older than him. Freud then moderates his views: “Whether the requirement of absolute truthfulness does not sin against the postulate of expediency and against the intentions of love I would not like to respond to in the negative without qualification […]” Having first praised Ferenczi for his honesty, Freud now takes a different course: “Truth is only the absolute goal of science, but love is a goal of life which is totally independent of science, and conflicts between both of these major powers are certainly quite conceivable.” But he refuses the tyranny of truth: “I see no necessity for principled and regular subordination of one to the other.” Freud knows or suspects that he is speaking to a man who has long been a slave to his belief in truth and in total revelation. Perhaps this is what impels him to remind his colleague of another character trait that makes their relation to psychoanalysis profoundly different, a trait that was to play an important role in the destiny of their collaboration: Freud does not have the therapeutic passion that animates Ferenczi, who never forgets his primary vocation as a doctor.

Far from possessing any furor sanandi, Freud finds patients “disgusting,” as we have seen. So he confesses to Ferenczi: “This need to help is lacking in me, and I now see why, because I did not lose anyone whom I loved in my early years.” Made intentionally or not, does this remark have interpretative value? Freud probably knows by now that, as the eighth child in a family of 12 children, Sándor was three when his little sister Vilma died before she was one. And Ferenczi has told him that he has long been haunted by the love he did not receive from an indifferent mother. But Freud does not have this double experience of trauma.

This first confession leads Freud to make another, more intimate than it appears, and again related to a troublesome need for truth associated with a passion for healing, of which he is wary when he sees it in Ferenczi: “I found this same personal motivation in Fliess. What is both strong and pathological in him comes from this.” How might Ferenczi, a sensitive man, have reacted to this comparison between him and Fliess? He must certainly have been intrigued by this reference to Fliess’ pathology, and by the fact that Freud was associating him with this man about whom he had talked to Ferenczi the previous summer, while they were in America. What effect did it have on Ferenczi, a doctor, whose father, also a doctor, died when the boy was 15, to hear Freud emphasise the origin of Fliess’ medical vocation: “The conviction that his father, who died from erysipelas after many years of nasal suppuration, could have been saved made him into a doctor, indeed, even turned his attention to the nose.” Why does Freud insist on drawing Ferenczi’s attention to what a theory – potentially delirious in Fliess’ case – may owe to some specific wound in someone’s personal history? “The sudden death of his only sister two years later, on the second day of a pneumonia, for which he could blame doctors, instilled in him the fatalistic theory of predetermined dates of death – as a consolation.” Then, Freud makes a remark that turns out to be more premonitory than he could have imagined: “This piece of analysis, unwanted by him, was the inner cause of our break, which he effected in such a pathological (paranoid) manner.” Again, could Ferenczi have remained unaffected by these threatening words, proffered as a delayed response to his recent declaration of love, and to the analysis of a dream sent to Freud? Would he not have been perplexed, or even made anxious, by Freud’s reference to a “piece of analysis” which resulted in the senseless ending of a passionate friendship?

Strictest secret!

Who is the Freud who wrote this surprising letter dated January 10, 1910? Is he the father of psychoanalysis, the experienced analyst, or simply a man struggling with his destiny? As an analyst, he guesses that Ferenczi has “a secret reason” for recounting this particular dream to him, a dream which, he says: “must also have a relation to me.” He offers an initial interpretation: “It is easy for me to find the motive for equating me with your father.” And he does not hesitate to disclose what he sees as a symptom in himself, namely the anticipation of his own death:

On the trip I behaved like someone who is taking his leave, who wants to set his house in order. In camp […] I had real appendix pains for the first time, and for at least a day I was quite despondent […]

In the letter, Freud gives Ferenczi an Oedipal interpretation as massive as it is dismissive: “So, that provides a basis for the identification. Again, as then, the death of the father is the signal for a great inner cleansing for you, and for an effort to bind the mother to you.” He even drives the point home by asking whether a certain reference in Ferenczi’s letter “is a compliment for the year just past, or whether it is connected with my imminent demise […]” Half in jest, Freud admits that his symptomatic fantasy is still at work: “Let us nevertheless firmly establish that I myself already decided quite a long time ago not to die until 1916 or 17. Of course, I don’t exactly insist upon it.” Although all this is asserted in a rather abrupt manner, Freud does not claim to be stating absolute truths, and his postulations remain playful. Still, he speaks with the authority of an analyst addressing a patient, albeit in the absence of any actual context of this kind. Unwittingly, Freud is reinforcing Ferenczi’s propensity for a self-analysis whose results are then reported to him. But this ceases to be the case when, after a long preamble, Freud starts to speak like an analyst addressing another analyst, both...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface: An unprecedented analytic adventure

- 1 Before the actual request for analysis (1908–1912)

- 2 Freud, the father of psychoanalysis and impossible analyst?

- 3 Laying the groundwork (1912–1913)

- 4 The actual analysis (1914–1916)

- 5 Budapest: Great expectations (1918–1919)

- 6 From public consecration to personal aspiration (summer 1918–spring 1919)

- 7 Personal analysis and analytic trajectory: Finished analysis? Endless path?

- Conclusion: Possibilities for the future

- Bibliography

- Index