Forensic Science

An Introduction to Scientific and Investigative Techniques, Fifth Edition

- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Forensic Science

An Introduction to Scientific and Investigative Techniques, Fifth Edition

About this book

Covering a range of fundamental topics essential to modern forensic investigation, the fifth edition of the landmark text Forensic Science: An Introduction to Scientific and Investigative Techniques presents contributions and case studies from the personal files of experts in the field. In the fully updated 5th edition, Bell combines these testimonies into an accurate and engrossing account of cutting edge of forensic science across many different areas.

Designed for a single-term course at the undergraduate level, the book begins by discussing the intersection of law and forensic science, how things become evidence, and how courts decide if an item or testimony is admissible. The text invites students to follow evidence all the way from the crime scene into laboratory analysis and even onto the autopsy table. Forensic Science offers the fullest breadth of subject matter of any forensic text available, including forensic anthropology, death investigation (including entomology), bloodstain pattern analysis, firearms, tool marks, and forensic analysis of questioned documents.

Going beyond theory to application, this text incorporates the wisdom of forensic practitioners who discuss the real cases they have investigated. Textboxes in each chapter provide case studies, current events, and advice for career advancement. A brand-new feature, Myths in Forensic Science, highlights the differences between true forensics and popular media fictions. Each chapter begins with an overview and ends with a summary, and key terms, review questions, and up-to-date references. Appropriate for any sensibility, more than 350 full-color photos from real cases give students a true-to-life learning experience.

*Access to identical eBook version included

Features

-

- Showcases contributions from high-profile experts in the field

-

- Highlights real-life case studies from experts' personal files, along with stunning full-color photographs

-

- Organizes chapters into topics most popular for coursework

-

- Covers of all forms of evidence, from bloodstain patterns to questioned documents

-

- Includes textboxes with historical notes, myths in forensic science, and advice for career advancement

-

- Provides chapter summaries, key terms, review questions, and further reading

-

- Includes access to an identical eBook version

Ancillaries for Instructors:

-

- PowerPoint® lecture slides for every chapter

-

- A full Instructor's Manual with hundreds of questions and answers—including multiple choice

-

- Additional chapters from previous editions

-

- Two extra in-depth case studies on firearms and arson (photos included)

-

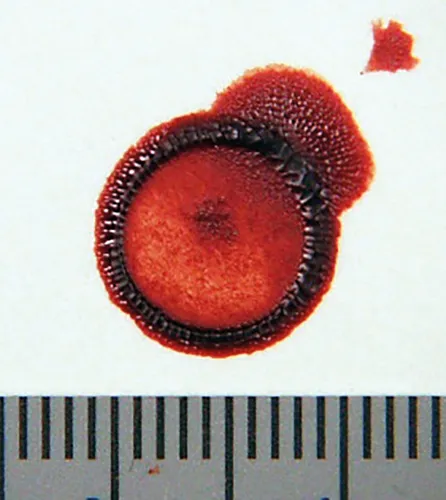

- Further readings on entomological evidence and animal scavenging (photos included)

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

(1902–1970)American forensic scientist

| Finding | Determined by | Story Supported |

| The brother called 911 | Cell phone records | Suspect |

| The stains on the suspect’s clothing were blood | Forensic laboratory analysis | Both |

| DNA results showed the blood to be that of the victim | Forensic laboratory analysis | Both |

| A gun was found at the scene | Crime scene investigator | Both |

| One set of fingerprints on... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Notes to the Instructor

- About the Editor

- Chapter 1 Justice and Science

- Chapter 2 Evidence

- Chapter 3 Crime Scene Investigation

- Chapter 4 Bloodstain Patterns

- Chapter 5 Medicolegal Investigation of Death

- Chapter 6 Postmortem Toxicology

- Chapter 7 Forensic Anthropology

- Chapter 8 Forensic Entomology

- Chapter 9 Biological Evidence

- Chapter 10 DNA Typing

- Chapter 11 Drugs and Poisons

- Chapter 12 Arson and Fire Investigation

- Chapter 13 Explosives and Improvised Explosive Devices

- Chapter 14 Fingerprints

- Chapter 15 Firearms and Tool Marks

- Chapter 16 Tread Impressions

- Chapter 17 Trace Evidence and Microscopy

- Chapter 18 Questioned Documents

- Chapter 19 Forensic Engineering

- Chapter 20 Computer Forensics

- Chapter 21 Behavioral Science

- Appendix A: Abbreviations

- Appendix B: Glossary

- Index