Multiple Regression and Beyond

An Introduction to Multiple Regression and Structural Equation Modeling

- 640 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Multiple Regression and Beyond

An Introduction to Multiple Regression and Structural Equation Modeling

About this book

Companion Website materials: https://tzkeith.com/

Multiple Regression and Beyond offers a conceptually-oriented introduction to multiple regression (MR) analysis and structural equation modeling (SEM), along with analyses that flow naturally from those methods. By focusing on the concepts and purposes of MR and related methods, rather than the derivation and calculation of formulae, this book introduces material to students more clearly, and in a less threatening way. In addition to illuminating content necessary for coursework, the accessibility of this approach means students are more likely to be able to conduct research using MR or SEM--and more likely to use the methods wisely.

This book:

• Covers both MR and SEM, while explaining their relevance to one another

• Includes path analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, and latent growth modeling

• Makes extensive use of real-world research examples in the chapters and in the end-of-chapter exercises

• Extensive use of figures and tables providing examples and illustrating key concepts and techniques

New to this edition:

• New chapter on mediation, moderation, and common cause

• New chapter on the analysis of interactions with latent variables and multilevel SEM

• Expanded coverage of advanced SEM techniques in chapters 18 through 22

• International case studies and examples

• Updated instructor and student online resources

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Multiple Regression

1

Simple Bivariate Regression

Simple Bivariate Regression

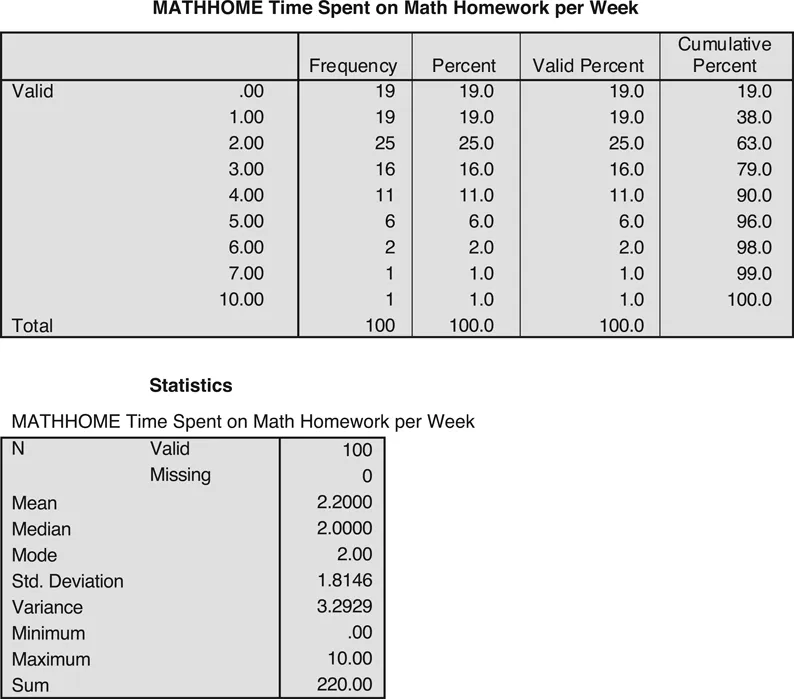

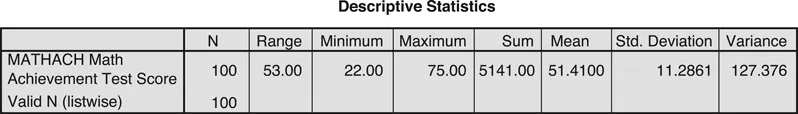

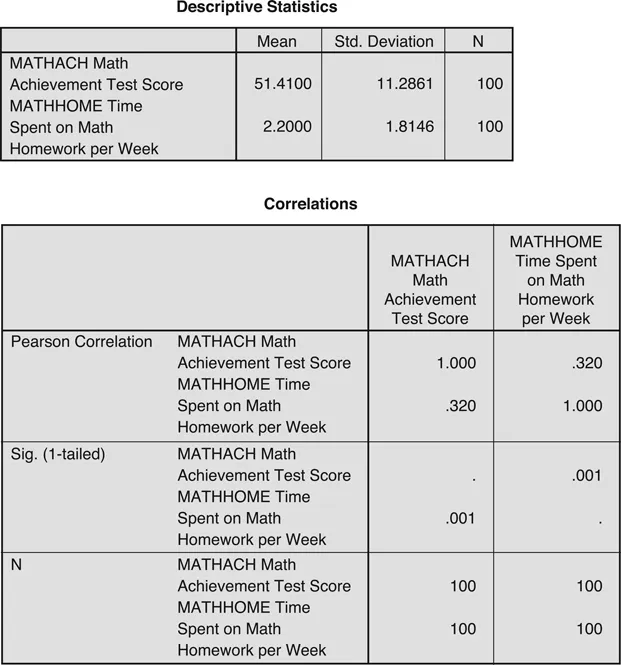

Example: Homework and Math Achievement

The Data

The Regression Analysis

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I Multiple Regression

- Part II Beyond Multiple Regression: Structural Equation Modeling

- Appendices

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app