No one ever talks about the moment you found out that you were White. Or the moment you found out you were Black. That’s a profound revelation. The minute you find that out, something happens. You have to renegotiate everything.

— Toni Morrison

A FEW YEARS AGO, we were invited to be a part of the planning team supporting a national anti-racism conference in the Seattle area. We felt honored to be the only two white women selected by a Black man to serve on the local executive leadership committee. We love this conference, and the fact that we were chosen for this important role said a lot in our minds about how awesome we are and how different (and let’s be honest, how much better) we are than other white people.

This started out as a collaboration run by a multiracial team and ended up with us micromanaging and trying to take control of every aspect of the planning process. With little provocation, we convinced one another that we had to take over for the “good of the conference.” After all, if we didn’t oversee and double-check each committee’s work, send out all of the emails, plan the agendas for our meetings, and call the conference organizer whenever we felt we needed to, who would?

While we understood how to follow the leadership of Black people in theory, when it came to our actual practice, we actively exhibited the white supremacy behaviors described by Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun in their article White Supremacy Culture, such as hoarding information, creating a sense of urgency, believing there is only one right way (the white way), thinking we were the only ones who knew the right way, and feeling a right to our comfort. At the same time, we opportunistically held onto the dichotomous idea that we were good people and, therefore, we couldn’t possibly be oppressive.

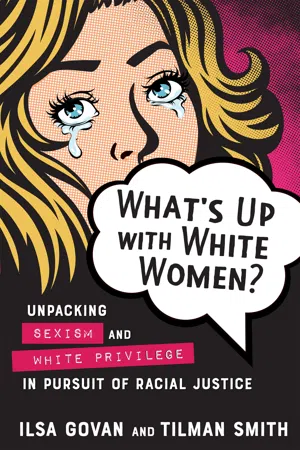

This left many of the People of Color (PoC) we were supposed to be partnering with shaking their heads in frustration and saying, “What’s up with white women?!” Although, to be honest, they already knew the answer.

Despite the fact that we joined the committee with years of experience in anti-racism work, we still resisted hearing any critical feedback from our colleagues during the planning of the conference. With time, we became more self-reflective, self-aware, open, and honest about our assumptions and behaviors on this team. Our hope in writing this book is to help both ourselves and other white women identify our racism more quickly, receive critical feedback more openly, and recover and make amends more graciously.

We write this book as a love letter to our white sisters. We hope it will help you recognize how we can engage in our everyday lives, work, and activism more effectively, and ultimately contribute, in many small ways, to our collective liberation. We hope it will help you sleep easier, knowing your actions are better aligned with how you see yourself and the core values that guide you. After all, the movement for social justice needs us to be brave, wide awake, and well-rested.

We also write this book as an offering to the People of Color who love, live with, work with, or simply have to interact with white women. Should you choose to read further, we hope this book will name and help explain some of the patterns you’ve witnessed in white women. We understand and own the harm that we inflict upon you regularly and humbly invite you to read these pages, not as a rationale for our behaviors, but as a window into our individual and collective journeys toward liberation.

We are at a particular moment in the United States when the need for white women to understand and effectively navigate multicultural partnerships has become a regular part of the public discourse. We’ve seen countless news stories of white women threatening Black lives by calling the police on Black people for anything from telling them to leash their dogs, to selling water, to sitting in a Starbucks. In the 2020 election, white women recently provided an even larger base of support for Donald Trump than in 2016. We have also shown up in large numbers at Black Lives Matter protests and worked to mobilize our siblings across the country to oppose racist violence.

At the same time as we’re seeing heightened awareness of racism, we are experiencing a public reckoning with sexism as witnessed in the Women’s March, #MeToo, and the upsurge in intersectional feminism. In all of these instances, white women have both hindered and helped to advance social justice.

This book explores the ways in which white women in the United States are positioned in a hierarchy between white men and People of Color, a buffer zone, due to our racial privilege and gender marginalization. We’ll examine how we internalize beliefs about our own inferiority due to sexism and, at the same time, internalize our racial superiority. Using theory, history, and true stories shared in focus groups, we highlight patterns in white women’s behaviors used to survive sexism in a patriarchal society and strategies we’ve developed to get ahead despite barriers. We’ll explore how these same patterns have been used to sabotage People of Color, resulting in deep conflicts and pain, as we prioritize our access to privilege. The heart of this book is a model of identity development where we name six distinct phases to explain the different ways white women navigate both sexism and white privilege: Immersion, Capitulation, Defense, Projection, Balance, and Integration.

Imagine standing on the edge of a canyon. Our internalized sexism and white superiority tell us to hold our ground and stay “safe.” This false sense of safety is a mindset that exploits people and the planet and will ultimately lead to physical, spiritual, and psychological destruction that actually makes us far less safe. On the other side of the canyon are our core values of justice, love, authentic relationships, and shared wisdom, to name a few. On that other side exists collective liberation — a concept we can easily say but not so easily envision — where we recognize the deep interconnection necessary to our survival as a species. The gap between feels like a frightening space. It is a space of practicing new ways of being and often failing in this practice. A space where we risk losing friendships and family who prefer the false comfort and dehumanization of racist systems designed to serve white people.

The canyon between our actions and beliefs can manifest like this: I value equity and relationship, but when I disagree with a Person of Color, I do so in a way that intentionally re-centers my white privilege in lieu of equity. For instance, a Chinese American man points out that our new policy might exclude communities who don’t speak English. Instead of asking questions for more understanding, I defend my decision and may reiterate that there is a time crunch, or that there are “rules” that need to be followed. While I may cloak my assertions in kindness and high regard for him and for all of the communities we serve (how I want to see myself), there is no doubt my arguments are meant to remind this man that I know more and better understand how systems work (how I am actually behaving).

White women stand on the edge of that canyon and decide whether we’re willing to leap across or stay put. We feel the allure of staying where we are and the stronger pull to live in a place aligned with our core values. In making the jump, we realize the canyon isn’t nearly as wide, or scary, or dangerous. It is merely a small crack in the earth. This book is a product of our experiences of trying to recognize and jump over those cracks, of understanding what keeps us frozen on one side and learning how to take an uncertain leap toward liberation. The beauty of our friendship and alliance as the authors of this work is that it allows us the option of holding hands and leaping over together.

The authors, who are both white women, first met over fifteen years ago when Tilman’s younger son was in Ilsa’s fifth-grade class. We remember this time differently. For Tilman, Ilsa provided a safe haven for her child while she worried about retaliation because of her activism in the school. Ilsa was in her third year of teaching fifth grade, still overwhelmed by, well, everything, and just happy to have a parent supporting her social and environmental justice agenda. We both saw something in the other that drew us together.

Our friendship and deep love for one another grew over time, as we worked separately and collaboratively as racial equity consultants and community activists. We partnered for many years in an anti-racist educator’s organization we co-created with other white women called WEACT, The Work of European Americans as Cultural Teachers. Tilman has seen Ilsa through the start and growth of her business, Cultures Connecting, with Dr. Caprice Hollins. Ilsa has seen Tilman through her work for racial justice in early childhood education as a coach, educator, and manager in nonprofits and government agencies.

Our relationship is based on a shared passion for uprooting systems of oppression, coupled with a fair amount of self-deprecating humor. We hold each other as mentors, asking ourselves in critical moments, “What would ‘Tilsan’ do?” We remind one another of the mantra we created together with our friend MG: “Stop, Take a Breath (STAB)”, where we engage in the healthy processing of reactivity and anger in our bodies.

By working together, we intentionally counter the sexist and racist competition so common among white women. Instead, we refer to ourselves as “accountabilibuddies,” holding up a mirror for one another in our efforts to counter systems of oppression.

As two white women learning and practicing together, we sometimes notice a gap between our core values and our actions, as evidenced by our experience planning the conference. Ilsa remembers sharing a long, self-righteous email she’d written to a Black woman in reaction to what she saw as an uninformed critique in one of her workshops. Tilman lovingly responded that, no matter what the critique was from the Black woman, Ilsa’s multiple links to articles and attempts to prove herself more knowledgeable than this woman weren’t the best cross-cultural practice and were probably rooted in anti-Blackness. Gulp. Now I’ll enjoy a slice of this humble pie and do something entirely different next time.

At one point when we were working on our book, Ilsa gently pointed out to Tilman, “You seem to have a lot of white women you don’t get along with.” Hmmm. Yep, I’ll be thinking about that for years to come.

This book would not have existed without our third Circle Belle (our band name if we had a band), MG Lentz. They helped co-create the identity development model that is the foundation of this book. Though they chose not to co-author the book, they helped create the framework and continue to inform our thinking.

From our conversations with MG, we developed a workshop for white women to gather and explore the unique intersection of our identities. What started in the spring of 2012 as a one-day session looking at the model we’d created quickly shifted to a two-day intensive with deep self-awareness work around how the interlocking experiences of sexism and white privilege have harmed us, and how we’ve harmed others. We collectively grew our knowledge of where white women are positioned in the United States in our ability to access institutional power. And we shared new skills and strategies to improve our relationships with People of Color and one another and address institutional oppression. The wisdom shared in these workshops by hundreds of women over the years greatly informs the content of this book. Many of the women who first met in these workshops have also stayed connected, continuing to grow and advocate for change together.

There is also no way we could have written this book without the insights from Women of Color. Inez Torres Davis, a Mujerista-Indigenous woman, wrote us,

So often white women use their own victimization as a wild card to get them out of the mess, an almost-free pass that means they don’t have near as much work to do around their privilege as white men have! I refuse to allow you to be ignorant of the blood that marks the places where white women...