eBook - ePub

Aesthetic Theology and Its Enemies

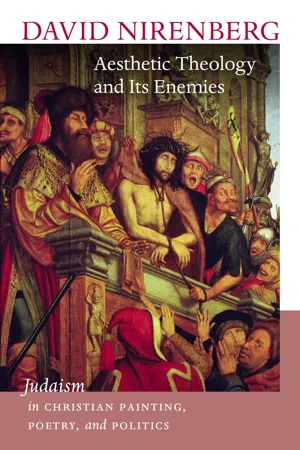

Judaism in Christian Painting, Poetry, and Politics

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Aesthetic Theology and Its Enemies

Judaism in Christian Painting, Poetry, and Politics

About this book

Through most of Western European history, Jews have been a numerically tiny or entirely absent minority, but across that history Europeans have nonetheless worried a great deal about Judaism. Why should that be so? This short but powerfully argued book suggests that Christian anxieties about their own transcendent ideals made Judaism an important tool for Christianity, as an apocalyptic religion—characterized by prizing soul over flesh, the spiritual over the literal, the heavenly over the physical world—came to terms with the inescapable importance of body, language, and material things in this world. Nirenberg shows how turning the Jew into a personification of worldly over spiritual concerns, surface over inner meaning, allowed cultures inclined toward transcendence to understand even their most materialistic practices as spiritual. Focusing on art, poetry, and politics—three activities especially condemned as worldly in early Christian culture—he reveals how, over the past two thousand years, these activities nevertheless expanded the potential for their own existence within Christian culture because they were used to represent Judaism. Nirenberg draws on an astonishingly diverse collection of poets, painters, preachers, philosophers, and politicians to reconstruct the roles played by representations of Jewish "enemies" in the creation of Western art, culture, and politics, from the ancient world to the present day. This erudite and tightly argued survey of the ways in which Christian cultures have created themselves by thinking about Judaism will appeal to the broadest range of scholars of religion, art, literature, political theory, media theory, and the history of Western civilization more generally.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Aesthetic Theology and Its Enemies by David Nirenberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Painting between Christianity & Judaism

The Lust of the Eyes

You shall not make yourself a carved image or any likeness of anything in heaven above or on earth beneath or in the waters under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them. For I, Yahweh your God, am a jealous God. . . . (Exod. 20:4–6)

The meaning of this passage—among the most influential in the development of Jewish, Christian, and Islamic art—has been endlessly contested. Does it forbid all art, or only graven sculpture? All images, or only those of living things? Sharp differences over its interpretation have marked the long history of debate about the making of images. But the general concern is clear: God considers certain forms of human interaction with certain kinds of objects a rival form of love, and He gets jealous.

Idols are an important subcategory of these dangerous objects of attention, but they are not the only ones. Both women and wealth, for example, appear so often in Hebrew scripture as rivals for God’s love that idolatry, adultery, and greed became intimately interrelated terms. The danger is even broader: any object in the world, seen or thought about in the wrong way, can constitute a rival to our love of God. Hence “the Lord also spoke to Moses and said: ‘Speak to the Israelites and tell them, for all generations to come, to put tassels on the hems of their clothes and work violet thread into the tassel at the hem. You will thus have a tassel, and the sight of it will remind you of all Yahweh’s orders and how you are to put them into practice, and not follow the dictates of your own heart and eyes, going whoring after diverse things . . .’” (Num. 15:38–40, italics my translation).1

The problem is not merely with images and idols, but with how we see and think about things themselves. In this crucial verse our eye’s attraction to those things is represented in terms of inappropriate sexual intercourse (Hebrew zonim, whoring; Vulgate’s Latin fornicantes, fornicating). The fringes that God ordained for their garments were meant to teach Israel’s children how to look at other objects, helping them know things chastely by disciplining their sight. Though at first blush this commandment may seem more cultic than philosophical, the potential for a vast aesthetic critique is spun into its blue threads. Much later Christian readers would recognize and develop that potential, as when Saint Augustine explained, circa 400, that the human “appetite for learning is called in the divine language ‘the lust of the eyes.’”

It is perhaps easier for us to recognize questions of cognition in ancient Greek debates about art than in Israelite ones. It is, after all, the Greek language that gave us English speakers our own etymological complex of words derived from the root for sight—words like idea, ideal, idol, ideology. It does not seem a long step from Aristotle’s claim that “the soul never thinks without a mental image” to John Locke’s view that “the understanding of a man in reference to all objects of sight, and the ideas of them,” is like a dark closet stacked with pictures obtained from the outside world of light.2 And the reason this step seems so short is that Greek thought systematized for what we call philosophy the gap between the sensible and the real, or the real and the ideal: gaps full of consequences for how the world would come to think about art.3

Still, just one example suffices to suggest that the aesthetic anxieties provoked by these Hellenistic gaps could take shapes very similar to the ocular fornications of the Hebrews. As we saw in the introduction, Plato developed a fundamental distinction between the physical senses and the reasoning intellect, between the world of sensible things (literally, aesthetics) and of “intelligibles.” The latter he thought immaterial, incorporeal (asōmata: Plato was among the earliest users of this Greek word). These incorporeal intelligibles were the truth of things—their ideai, or “Forms,” in his specialized vocabulary, corresponding to our English “idea”—rather than of their image or mere appearance (eidolon, from whence our English “idol”). Theirs is the domain of the “greater mysteries”: the transcendent world of metaphysics toward which Plato orients his philosophy.4

But although Plato sometimes imagines that our souls once dwelt in such a metaphysical world, “unsigned” and “unentombed” by the body (as he puns in the Phaedrus), he is aware that they no longer do. In this world our soul is imprisoned by the body “like an oyster by its shell,” and we can only reach toward truth through the senses. The task is not easy, as Plato goes on to explain in this same passage (Phaedrus 250A-E), because sensible things can lead away from truth as easily as they can toward it. He uses the example of sight, “the keenest mode of perception vouchsafed us through the body,” and of beauty, of all “beloved objects” the “most manifest to sense and most lovely.” How does the sight of sensible beauty affect us? It can send us “after the fashion of a four-footed beast” to “beget offspring of the flesh” and “consort with wantonness” (recall the vocabulary of Num. 15). Or conversely, it can awaken our memory of beauty in that other world, the metaphysical world “that truly is,” and stimulate our soul’s striving toward it.

The discussion in the Phaedrus is about the attraction of one human being toward the beauty of another, but the ambivalence in question affects all forms of cognition that depend on sight and beauty.5 The prisoners in the famous cave of Plato’s Republic confront a similar problem: they know only the shadows of puppets, statues, and artifacts paraded on the wall before them. For them, “truth is nothing other than the shadow of artificial things.” The prisoner who has been briefly dragged into the light—that is, the philosopher—also depends on sight for knowledge, but with this crucial difference: he knows that the sights in the cave are “idols” and “phantasms” and struggles to turn his soul’s attention toward “that which is.”

Plato does not present the ideal here as freedom from images, or as keenness of sight. There is no freedom from images to be had in this world: even the allegory of the cave is itself an “image,” as both Socrates and his interlocutor Glaucon realize. As for keenness of sight, in the case of a vicious soul “the sharper it sees, the more evil it accomplishes.” The difference between falsity and truth, according to Plato, lies not in qualities of vision but in the orientation of the soul itself, which needs to be “turned around toward the true things” and away from their mere appearance (Republic 514–19). It is the task of philosophy to effect this conversion of the soul’s habits of attention and perception. But there are other arts, such as poetry, painting, and sculpture, that tend to effect conversions in the opposite direction. These misdirect the soul because they make their appeal directly to the world of things through the senses, rather than calling attention to the gap between appearance and reality.6

Mimēsis—a Greek word sometimes translated as representation, sometimes a bit more reductively as imitation, and sometimes left untranslated—is the key term here. Plato considers many arts to be mimetic in that they make things at some remove from the truth. The couch maker, for example, makes a couch, not the ideal form of a couch, and in this sense his product is but a shadow of the “real.” But some artists are more mimetic than others, among them the painter and the poet, who make representations of everything. He “produces earth and heaven and gods and everything in heaven and everything in Hades under the earth.” This promiscuity insults Plato’s sense of the proper specialization of each art (technē). Worse, it means that what the painter and the poet produce are not real even in the couch’s limited sense: “they look like they are; however they surely are not in truth” (596 C-E).7

Poets and painters stand further from the truth than other craftsmen because they are “imitators of phantoms of virtue” rather than of virtue itself. Not only do their works appeal to “the soul’s foolish parts,” but this gratification does not lead toward any greater knowledge of things: “The painter will make what seems to be a shoemaker to those who understand as little about shoemaking as he understands, but who observe only colors and shapes” (600E–601A). The result of this preference for the sensible over the true is that painting (like poetry) “produces a bad regime in the soul of each private man” (605C). It is the philosopher’s task to produce the opposite—a good regime both for the person and the polity—by warning souls about the sensible and orienting them toward the true. Philosophy strives to make of every soul a critic of art.

Criticism need not mean elimination. Plato often insists that if oriented toward the good, the power of mimesis can be put to positive work. In the Laws, for example, he does prohibit certain forms of mediation and representation (such as money) that he deems irremediably corrupting to the polity. But he does not banish painting. Instead, “the Athenian” endorses a certain type of art by praising the example of Egypt, which “long ago recognized that poses . . . must be good, if they are to be habitually practiced by the youthful generation of citizens. So they drew up the inventory of all the standard types, and consecrated specimens of them in their temples. Painters . . . were forbidden to innovate on these models,” with the result that “the work of ten thousand years ago . . . [and] that of today both exhibit an identical artistry” (Laws 656E–657A).

Plato’s praise of the Egyptians was aimed directly at what he considered the misguided aesthetic fashions of his own day, which celebrated artists for feats of naturalism and delighted in their invention of techniques of illusion. Yet through his criticism, Plato was also issuing painting a passport into the age of transcendence. In a world of ideas in which matter was increasingly stigmatized and the appearance of things increasingly deemed distant from their truth, painting was at risk of becoming the enemy of philosophy. Plato outlined the reasons for that enmity and its dangers, but he also set forth the terms by which it might be overcome. If art would submit to ontology, he suggested, it could labor in the service of the good.

Of course Plato was not the only thinker about art in the ancient world. Aristotle, for example, had a very different understanding of the nature of the soul and the senses, of the relationship between the real and the ideal, and therefore of the perils and opportunities of representation. I’ve focused so much on Plato’s criticism (and defense) of the mimetic arts because both would have such varied and influential futures in the many Hellenistic schools of thought into which Christianity expanded. By the end of Late Antiquity we might say that Neoplatonism had conquered even Aristotle, so that Peripatetic aesthetics were often read through Platonic eyes. But we need not take the long detours necessary to prove the point. Histories of ancient philosophy, like those of Israelite prophecy, concern us here only insofar as we need to be convinced that they provided the conceptual tools with which early Christians carved out their own concerns about the gap between the material and the real.

Judaizing Aesthetics

We can see both those conceptual tools being put to work already in the earliest Christian writings. Recall the brief history of humankind’s knowledge of the divine provided by Saint Paul in chapter 1 of his Epistle to the Romans:

Ever since the creation of the world, the invisible existence of God and his everlasting power have been clearly seen by the mind’s understanding of created things. And so these people have no excuse. . . . While they claimed to be wise, in fact they were growing so stupid that they exchanged the glory of the immortal God for an imitation [homoiōma, counterfeit], for the image [eikōon] of a mortal human being, or of birds, or animals, or crawling things. (Rom. 1:20–23)

This astonishing passage takes the Mosaic law’s concern with the worship of images and conflates it with the ontological preoccupations of Platonic philosophy to arrive at a general critique of gentile knowledge of created things in the world.

In Galatians Paul had developed a Jewish version of this error, accusing Judaizers of worshipping the outer fleshy appearance of things rather than their inner spiritual reality. In Romans he developed this theme, applying it to the nature of Judaism itself: “The real Jew is the one who is inwardly a Jew, and real circumcision is in the heart, a thing not of the letter but of the spirit” (2:29). In that epistle he also located the source of the Jews’ ontological bind in the Mosaic law itself: “The commandment was meant to bring life but I found it brought death. . . . It is by means of the commandment that sin shows its unbounded sinful power.” The law of Moses cannot free or save. At best it can make me aware that I “am a prisoner of that law of sin which lives inside my body.” “Only the law of the Spirit which gives life in Jesus Christ” can set me free (7:7–25; 8:2).

Readers of Paul discovered multiple meanings in his writings about Jews, the Law, and the flesh. In the Epistle to the Romans alone, and specifically on the question of how humans relate to God through sensual perception of things in the world, they could find justification for two very different aesthetics. Chapter 1 condemned idolatry but held out the hope that through the sight of created things we can come to knowledge of the creator. Chapter 7 stressed the alienation from truth that came with embodiment and removed any hope that the law God gave to Moses could overcome the law of sin at work in our flesh. Chapter 1 would inspire those schools—sometimes called Neoplatonic because influenced by Plotinus and Porphyry’s readings of Plato—that ta...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Troubling Transcendence

- Chapter One: Painting between Christianity and Judaism

- Chapter Two: Every Poet Is a Jew

- Chapter Three: Judaism as Political Concept

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Color plates