eBook - ePub

American Jewish History

A Primary Source Reader

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

American Jewish History

A Primary Source Reader

About this book

Presenting the American Jewish historical experience from its communal beginnings to the present through documents, photographs, and other illustrations, many of which have never before been published, this entirely new collection of source materials complements existing textbooks on American Jewish history with an organization and pedagogy that reflect the latest historiographical trends and the most creative teaching approaches. Ten chapters, organized chronologically, include source materials that highlight the major thematic questions of each era and tell many stories about what it was like to immigrate and acculturate to American life, practice different forms of Judaism, engage with the larger political, economic, and social cultures that surrounded American Jews, and offer assistance to Jews in need around the world. At the beginning of each chapter, the editors provide a brief historical overview highlighting some of the most important developments in both American and American Jewish history during that particular era. Source materials in the collection are preceded by short headnotes that orient readers to the documents' historical context and significance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access American Jewish History by Gary Phillip Zola, Marc Dollinger, Gary Phillip Zola,Marc Dollinger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Jewish History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Brandeis University PressYear

2014Print ISBN

9781611685107, 9781611685091eBook ISBN

97816116851141 Creating Community

THE AMERICAN JEWISH EXPERIENCE DURING THE COLONIAL PERIOD, 1654–1776

For colonial-era Jews, immigration, acculturation, and civic status emerged as the central themes of the American experience. In some ways, colonial Jews, who numbered just hundreds in the seventeenth century and a few thousand by the time of the American Revolution, had certain characteristics in common. A significant number of colonial Jews worked in the commercial trades and lived in economic centers such as Newport, New York, Philadelphia, Savannah, and Charleston. Whether they were of Central European ancestry or traced their roots to the great Jewish community of the Spanish empire, colonial Jews worshiped according to the Spanish-Portuguese liturgical rite. These pioneering Jewish settlers also faced common challenges and experienced similar opportunities as they adapted to their new lives on the North American continent.

Yet their experiences as immigrants and then as colonial Jews also reflected a broad, and varied, acculturation process. Different local laws and customs in each of the thirteen colonies revealed the competing motives of British colonialism. The first Jewish community in North America sprang to life in September 1654 when twenty-three refugees from the Dutch colony of Recife, Brazil, arrived in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. The story of this first Jewish settlement reveals that these pioneering Jews were determined to secure their status. They sought to remain in the colony, and they asserted themselves in an effort to ensure their civil rights. This trend continued after New Amsterdam became New York. Later, Jews began to settle in other North American colonies such as Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Georgia, where the allure of the mercantilist system was particularly strong in these colonies’ port cities. Yet these Jews wanted more than economic opportunity; they also wanted civil equality and a social setting wherein they could fulfill their desire to worship openly as Jews. This is why they avoided those colonies that were founded as havens for particular Christian religious groups, such as the Puritans, which tended to limit the immigration and influence of religious outsiders. Across colonial America, Jews strove to achieve an elusive goal: civil equality in a Christian-dominated society. What that meant, and how it was achieved, differed among American Jews, as the documents that follow illustrate.

Colonial Jews also developed new approaches to religious life. With such small numbers, American Jews in this period lacked the critical mass to build large Jewish organizational structures or to establish the kind of associational networks that would arise during the nineteenth century; therefore, colonial Jewish life was synagogue-centered. Jewish colonists interacted freely with non-Jews, and the phenomenon of intermarriage—an unusual occurrence for Jews who lived in the Old World—became a familiar trend in colonial America. It has been estimated that perhaps as many as one in every four Jews married a partner from a non-Jewish family.

American Jews fashioned their religious lives according to Jewish tradition as well as to the larger religious and civic culture of their surrounding communities. Synagogues, for example, tended to emulate current architectural trends. As the movement for greater democratic control of American government institutions gained traction in the colonies, so too did the democratic spirit influence the governance documents of the American synagogue and, ultimately, other Jewish organizations.

These major themes from the colonial period would recur throughout the course of American Jewish history.

BEGINNINGS

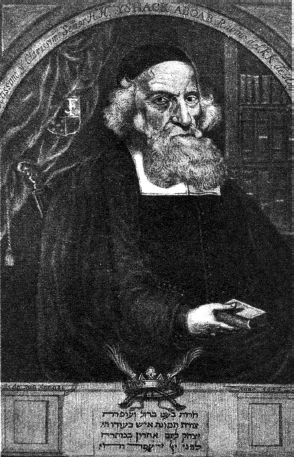

1.01—RABBI ISAAC ABOAB DE FONSECA, RECIFE, BRAZIL, N.D.

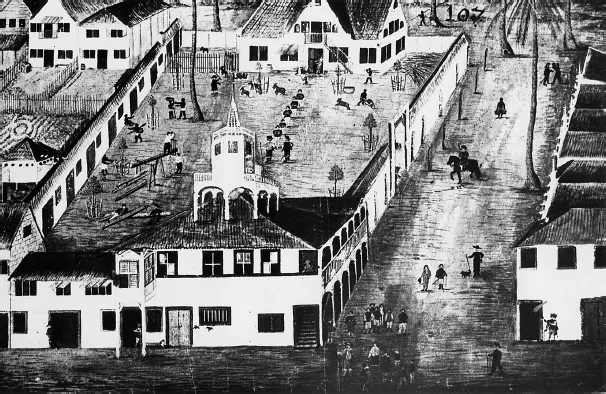

Rabbi Isaac Aboab de Fonseca (1605–1693) served as the spiritual leader of Recife’s Jews from 1642 until 1654. Portuguese-born, Aboab was raised in France and Amsterdam. He became a rabbi while in Amsterdam and later served the community’s Congregation Bet Israel. His first years in Recife witnessed a flourishing Jewish community aided by Dutch colonial authorities who respected religious pluralism. Beginning in 1646, though, a series of Portuguese raids on Recife unsettled its Jewish community. When Portuguese forces recaptured their onetime colony in 1654, they evicted its Jewish residents, who fled to Amsterdam, the Caribbean, as well as the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam in North America. The second image is a painting of Recife by Zacharias Wagenaer (1614–1668). Wagenaer (also spelled Wagener, Wagenaar, or Wagner) was the son of a German illustrator who lived in the Dutch colony during the late 1630s.

Source: PC-11, AJA.

1.02—RECIFE, BRAZIL, BY ZACHARIAS WAGENAER, N.D.

Source: PC-3616, AJA.

1.03—PETER STUYVESANT, MANHATTAN, TO THE AMSTERDAM CHAMBER OF DIRECTORS, SEPTEMBER 22, 1654

In the letters that follow, Dutch colonial governor Peter Stuyvesant (1612–1672) communicates with the Dutch West India Company on the status of New Amsterdam’s recent Jewish arrivals. While Stuyvesant opposed a permanent Jewish community in his jurisdiction, owners of the West India Company, which included some Jews, rallied behind the Jewish immigrants. In April of 1665, the directors informed Stuyvesant of their decision. The Jewish refugees would be allowed to “travel and trade” and to “live and remain” in New Netherland “provided the poor among them shall not become a burden to the company or to the community . . . [and] be supported by their own nation.”

The Jews who have arrived would nearly all like to remain here, but learning that they (with their customary usury and deceitful trading with the Christians) were very repugnant to the inferior magistrates, as also to the people having the most affection for you; the Deaconry [which takes care of the poor] also fearing that owing to their present indigence [due to the fact that they had been captured and robbed by privateers or pirates] they might become a charge in the coming winter, we have, for the benefit of this weak and newly developing place and the land in general, deemed it useful to require them in a friendly way to depart; praying also most seriously in this connection, for ourselves as also for the general community of your worships, that the deceitful race,—such hateful enemies and blasphemers of the name of Christ,—be not allowed further to infect and trouble this new colony, to the detraction of your worships and the dissatisfaction of your worships’ most affectionate subjects.

Source: As printed in JAW, 29–30. Reprinted with permission of the AJHS, from PAJHS 18 (1909): 4–5, 19–21.

1.04—AMSTERDAM JEWRY’S SUCCESSFUL INTERCESSION FOR THE JEWISH IMMIGRANTS, JANUARY 1655

To the Honorable Lords,

Directors of the Chartered West India Company,

Chamber of the City of Amsterdam

The merchants of the Portuguese nation [the Sephardic Jewish community] residing in the City [of Amsterdam] respectfully remonstrate to your Honors that it has come to their knowledge that your Honors raise obstacles to the giving of permits or passports to the Portuguese [Sephardic] Jews to travel and to go to reside in New Netherland, which if persisted in will result to the great disadvantage of the Jewish nation. It can also be of no advantage to the general Company but rather damaging.

There are many of the nation who have lost their possessions at Pernambuco and have arrived from there in great poverty, and part of them have been dispersed here and there. [Pernambuco, or Recife, the stronghold of Dutch Brazil, was captured by the Portuguese, January 1654.] So that your petitioners had to expend large sums of money for their necessaries of life, and through lack of opportunity all cannot remain here [in Holland] to live. And as they cannot go to Spain or Portugal because of the Inquisition, a great part of the aforesaid people must in time be obliged to depart for other territories of their High Mightinesses the States-General [the Dutch government] and their Companies, in order there, through their labor and efforts, to be able to exist under the protection of the administrators of your Honorable Directors, observing and obeying your Honors’ orders and commands. [The West India Company owned the young Dutch colony of New Netherland.] It is well known to your Honors that the Jewish nation in Brazil have at all times been faithful and have striven to guard and maintain that place, risking for that purpose their possessions and their blood. . . .

Your Honors should also consider that the Honorable Lords, the Burgomasters of the City and the Honorable High Illustrious Mighty Lords, the States-General, have in political matters always protected and considered the Jewish nation as upon the same footing as all the inhabitants and burghers. Also it is conditioned in the treaty of perpetual peace with the King of Spain [the treaty of Muenster, 1648] that the Jewish nation shall also enjoy the same liberty as all other inhabitants of these lands.

Your Honors should also please consider that many of the Jewish nation are principal shareholders in the [West India] Company. They having always striven their best for the Company, and many of their nation have lost immense and great capital in its shares and obligations. . . .

Therefore the petitioners request, for the reasons given above (as also others which they omit to avoid prolixity), that your Honors be pleased not to exclude but to grant the Jewish nation passage to and residence in that country; otherwise this would result in a great prejudice to their reputation. Also that by an Apostille [marginal notation] and Act the Jewish nation be permitted, together with other inhabitants, to travel, live, and traffic there, and with them enjoy liberty on condition of contributing like others. . . .

Source: As printed in JAW, 30–31. Reprinted with permission of AJHS, from PAJHS 18 (1909): 4–5, 9–11.

1.05—EXTRACT FROM REPLY BY THE AMSTERDAM CHAMBER OF THE WEST INDIA COMPANY TO STUYVESANT’S LETTER, APRIL 26, 1655

Honorable, Prudent, Pious, Dear, Faithful [Stuyvesant] . . .

We would have liked to effectuate and fulfill your wishes and request that the new territories should no more be allowed to be infected by people of the Jewish nation, for we foresee therefrom the same difficulties which you fear. But after having further weighed and considered the matter, we observe that this would be somewhat unreasonable and unfair, especially because of the considerable loss sustained by this nation, with others, in the taking of Brazil, as also because of the large amount of capital which they still have invested in the shares of this company. Therefore, after many deliberations we have finally decided and resolved to apostille . . . upon a certain petition presented by said Portuguese Jews that these people may travel and trade to and in New Netherland and live and remain there, provided the poor among them shall not become a burden to the company or to the community, but be supported by their own nation. You will now govern yourself accordingly.

Source: As printed in JAW, 32–33. Reprinted with permission of AJHS, from PAJHS 18 (1909): 4–5, 8.

1.06—MOSES LOPEZ BECOMES A NATURALIZED CITIZEN, 1741

Moses Lopez (1706–1767), like his younger and better-known half-brother, Aaron (1731–1782), was born in Portugal to a wealthy converso family. Moses immigrated to New York in 1740–1741 before he and his brother settled in Newport, Rhode Island. The following document demonstrates that Moses enjoyed distinction as one of the first American Jews to become a British citizen under the 1740 British Naturalization Act, which eased the process for gaining citizenship and created avenues for both Jews and Catholics to enjoy full civil equality.

George the Second, by the Grace of God of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, etc. To all to whom these presents shall come or may concern, greeting:

Know ye that it appears unto us by good testimony that Moses Lopez, of the city of New York, merchant, being a person professing the Jewish religion, hath resided and inhabited for the space of seven years and upwards within some of our colonies in America, and that the said Moses Lopez, on the twenty third day of October last, betwixt the hours of nine and twelve in the forenoon of the same day, in our Suprem[e] Court of Judicature of our Province of New York, before our judges of our said court, did take and subscribe the oaths of allegiance and supremacy and the abjuration oath, pursuant to the directions of an act of our Parliament of Great Britain, made and passed in the thirteenth year of our reign, entitled “An Act for Naturalizing Such Foreign Protestants and Others therein Mentioned as Are Settled or Shall Settle in Any of His Majesty’s Colonies in America,” and that the said Moses Lopez’s name is registred as a natural born subject of Great Britain, both in our said Supreme Court and in our Secretarie’s office of our said province, in books for that purpose severally and particularly kept, pursuant to the directions of the aforesaid act.

In testimony whereof we have caused the great seal of our said Province of New York to be hereunto affixed. Witness our trusty and well beloved George Clarke, Esq., our Lieutenant Governor and Commander in Chief of our Province of New York and the territories thereon depending in America, etc., the thirteenth day of April, Anno Domini 1741, and in the fourteenth year of our reign.

George Joseph Moore, deputy secretary

Source: As printed in AJ, 201. MS-107, Nathan/Kraus Family Collection, 1738–1939, AJA.

1.07—BARNARD GRATZ TO MICHAEL GRATZ, GIVING ADVICE ON IMMIGRATING TO PHILADELPHIA, NOVEMBER 20, 1758

Barnard Gratz (1738–1801), born in Langendorf, Upper Silesia (which would become part of Germany), immigrated to Philadelphia in 1754, where he became a merchant. By 1758, he was prepared to enter business with his brother, Michael (1740–1811), who had already immigrated to London from Langendorf. In 1759, the brothers reunited in Philadelphia, where they eventually won contracts to supply the colonial government with goods traded from various American Indian tribes.

Greetings to my dearly beloved brother who is as dear to me as my own life, the young man, Yehiel [Michael]—long may he live—that princely, scholarly, and incomparable person:

I report that I am in good health, and I hope you are too.

I learn, dear brother, from the letter...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Creating Community: The American Jewish Experience during the Colonial Period, 1654–1776

- Chapter 2. Forging a Nation: The American Jewish Experience during the Revolution and the Early National Period, 1776–1820

- Chapter 3. Migrations across America: Jews in the Antebellum Period, 1820–1860

- Chapter 4. Slavery and Freedom: American Jews during the Civil War and Reconstruction, 1861–1879

- Chapter 5. The Gilded Age and Progressive Era: American Jewish Life, 1880–1918

- Chapter 6. American Jews between the World Wars, 1918–1941

- Chapter 7. Waging War: American Jews, World War II, and the Shoah, 1941–1945

- Chapter 8. American Jewish Life, 1945–1965

- Chapter 9. Turning Inward: Jews and American Life, 1965–1980

- Chapter 10. Contemporary America: Jewish Life since 1980

- Index