- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this clear-minded but sobering book, Michael M. Kaiser assesses the current state of arts institutions—orchestras; opera, ballet, modern dance, and theater companies; and even museums. According to Kaiser, new developments in the twenty-first century, including the Internet explosion, the death of the recording industry, the near-death of subscriptions, economic instability, the focus on STEM education in schools, the introduction of movie-theater opera, the erosion of newspapers, the threat to serious arts criticism, and the aging of the donor base have together created tremendous challenges for all arts organizations. Using Michael Porter's model of industry structure to describe how industries evolve, Kaiser argues persuasively that unless steps are taken now, midsized performing arts institutions will have all but evaporated by 2035. Only the largest arts organizations will survive, with tickets priced for the very wealthy and programming limited to the most popular and lucrative productions. Kaiser concludes with a call to arms. With three extraordinary decades' experience as an arts administrator behind him, he advocates passionately for risk-taking in programming and more creative marketing, and details what needs to happen now—building strong donor bases, creating effective boards, and collective action—to sustain the performing arts for generations to come.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Curtains? by Michael M. Kaiser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Nonprofit Organizations & Charities. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | AMERICA THE BEAUTIFUL THE ARTS EXPLOSION, 1950–2000 |

Those of us who were born in the United States of America in the decade following World War II have lived charmed lives. Our world has continuously changed and expanded in remarkable and magical ways. Most of us are more educated, wealthier, and better traveled than our parents. We were born in the age of television and have lived into the age of Netflix and Hulu. We witnessed the development of computers and lived into the age of iPads. Wary of long-distance telephone charges as children, we now speak at will, and at very low cost, on our smart phones. That is, when we speak at all, because we can e-mail and text to anyone at any time at almost no cost. Along the way we adopted, then discarded, fax machines, VCRs, cordless telephones, and numerous other gadgets that seemed like revelations when they were introduced and now seem merely quaint.

Our lives have expanded in other ways. We now travel everywhere, at relatively low cost. Airline ticket prices have fallen 40 percent since the 1950s. In 1958, 38 million people flew; fifty years later, that number was 809 million! We eat foods from every corner of the earth. I didn’t taste pizza until I was ten years old; our children know the difference between sushi and sashimi. Where we once read a daily newspaper, we now access our information in real time: even twenty-four-hour news stations struggle to keep market share when so many of us get our news online, faster than it can be produced for television. We used to buy expensive encyclopedias; now we use Wikipedia for free. Instead of visiting a library to research a school paper, students now log on and search, then cut and paste.

These technological changes have been accompanied by earthshaking social changes. We have lived through efforts to secure civil rights, women’s rights, reproductive rights, and gay rights. (Hard as it might be for many younger people to imagine, there was even a battle to secure the right to divorce.) And while we still have much to accomplish, we now live in a more equitable society than we were born into.

Much else has changed over the past seventy years. For those of us who care about the arts—and a remarkable number do—there has been an explosion in the accessibility and diversity of live performances and visual arts exhibitions. Except for a few of our venerable museums, orchestras, and opera companies, most of the arts organizations in today’s United States were formed after World War II. With some notable exceptions, many of our most famous modern dance companies, theater organizations, ballet companies, and jazz groups also were spawned in the second half of the twentieth century, including the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Steppenwolf Theatre Company, New York City Ballet, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and so on. (The same is true for many countries across the globe. Even when some of the major arts venues are older, the ensembles operating within them are young. The Royal Opera House, for example, was built in the mid-nineteenth century but the Royal Opera Company was formed in 1946.)

The burst of national pride, enthusiasm, and economic development that followed the war resulted in a remarkably fertile period of creativity in the United States. Working in that decade were the playwrights Tennessee Williams, Eugene O’Neill, and Arthur Miller; the composers Leonard Bernstein and Aaron Copland; the moviemakers Frank Capra and Alfred Hitchcock; the jazz artists Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington, and Charlie Parker; and the choreographers Jerome Robbins, Agnes de Mille, and Martha Graham. We still revere the great movies, musicals, songs, novels, plays, and ballets that were created in that remarkable time.

And with the emergence of every important new artist, America’s hunger for arts experiences only increased. Audiences were large, costs were relatively low, and the great and the good in each community were willing to underwrite the expenses that ticket sales could not cover.

This hunger for arts experiences was fed by television viewing. While those born after 1970 might not believe it, serious arts played a vital role in the development of commercial television. Many popular programs promoted the great opera singers, actors, and dancers of the time, including The Bell Telephone Hour, Playhouse 90, and The Ed Sullivan Show.

It is amazing to recall that Joan Sutherland was regularly featured in prime time on network television. Although an astonishing talent, Sutherland was not the most telegenic person; she would have been unlikely to get the bookings today. But a generation of Americans enjoyed Maria Callas, Isaac Stern, and Rudolph Nureyev, while many families huddled around their television sets to watch Leonard Bernstein conduct Young People’s Concerts with the New York Philharmonic on CBS from 1958 until 1972! By contrast, the sole regularly scheduled network television program to feature classical music today is The Kennedy Center Honors, broadcast on one night each December and featuring only a short segment on the classical arts.

This appreciation for the arts was reflected in the lives of our leading politicians. President John F. Kennedy and his wife Jacqueline famously turned the White House into a salon where great artists and thinkers and writers could meet. When the Kennedys hosted the politically controversial cellist Pablo Casals in 1961, his performance made international news. The same was true of a gathering of Nobel Prize winners, of concerts by young artists, and other events.

As a result of the emergence of great talent and heightened visibility, the period from 1945 until 2000 saw an astonishing proliferation of arts organizations. And not just in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. Important arts institutions were created in virtually every city and state in the Union, including Santa Fe, New Mexico; Cooperstown, New York; and Montgomery, Alabama. Today there are tens of thousands of arts organizations spread across the nation which attract many millions of visitors and inspire countless artists and audience members.

THE INCOME GAP

Another principal factor behind this artistic golden age was the willingness of an increasing number of people to support their local arts institutions, with financial contributions ranging from modest levels to much larger amounts. While it is true that, from the beginning of time, humans have had the twin needs to create and to be entertained, the history of arts organizations is entwined with the history of the people who are willing to pay for them. The visual and performing arts have never paid for themselves.

Why? Unlike most other industries, artists and arts institutions have never found a way to consistently boost worker productivity. In almost every other profitable industry, workers become more productive quarter after quarter. It now takes fewer person-hours to make a car or a blender—or to complete a banking transaction or send an oil invoice—than it did last year. This critical element affects every business; if workers get more productive, the cost of making the good or providing the service is less than it would be if worker productivity was flat.

Those of us in the arts, however, have a difficult time improving worker productivity. Musicians do not play Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony faster every year, nor are any fewer dancers required to perform Serenade than when George Balanchine first created it in 1934. We do not ask sculptors to sculpt more quickly every year, nor do we ask composers to write a score in less time.

As a result, arts institutions suffer from a higher rate of inflation than the steel, automobile, or banking industries, where improvements in worker productivity lower one cost of production (total salaries) and offset, at least in part, inflation in other costs.

The fact that costs rise faster for arts organizations than for other industries is often misread as “artists don’t handle money well” or “artists are wasteful.” Many board members believe that if an arts organization were managed carefully, it would turn a profit. They cannot understand why an organization that makes something people like should run at a perpetual deficit.

This corporate prejudice can affect the way they govern their arts organization, encouraging them to try to cut budgets or to avoid addressing annual fund-raising requirements. Such board members start from the belief that arts managers are doing something wrong. They think that if corporate managers could run the arts organization, then it would become profitable, that if arts managers were smarter, fund-raising targets could be lower. They are simply wrong.

In truth, arts organizations are among the most efficient in the world, doing an immense amount of work with very small budgets. Even the largest arts organizations have modest budgets compared to ordinary corporations. And yet, many of the world’s most important arts institutions have created huge brand awareness, with marketing commitments that are a small fraction of their less-well-known corporate counterparts. We have to be efficient because we serve so many masters: our board members, our audience, our donors, the press, and our peers.

To make matters more difficult, the opportunity for earned income in the arts comes with some built-in limitations. In many cases, the possible income for a given performance is limited by the number of seats in the theater. The Opera House at the Kennedy Center, for example, has 2,300 seats; that number has remained unchanged since it opened in 1971. Unlike most corporations, which can spread their costs over an ever-increasing customer base, each performance in this venue can serve only 2,300 patrons. Although our overheads grow quickly, our audience per show—and hence our real revenue for that show—is fixed.

When I was running the Alvin Ailey organization, I brought the dancers to perform at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, a beautiful outdoor amphitheater built into the base of the Acropolis in Athens, Greece. It is one of the most amazing places in the world to experience a performance. The dancers were thrilled to perform on this ancient stage, with the Acropolis lit by the moon. I marveled, however, that the number of seats for the performances was the same as when the theater was built almost 2,000 years ago. There had been no opportunity for increases in real earned income, despite a huge increase in costs per performance!

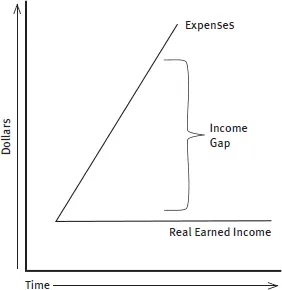

Although arts institutions typically cannot increase the real earning potential for each performance, their costs rise quickly because of the productivity problem. This causes an income gap that grows larger and larger every year. This economic dilemma has faced arts groups since the time of the construction of the Odeon of Herodes Atticus. When revenue growth is slower than expense growth, deficits are the result.

INCOME GAP

FILLING THE INCOME GAP

So what can we do to fill this income gap? One way to balance our budgets is to continue to raise ticket prices—as we have done for the past thirty years. But ticket prices have now grown so high that we have hit a point of diminishing returns: when going to the theater is too expensive, people stop going and revenue falls. Today, a pair of center orchestra tickets to the Metropolitan Opera cost $600! For just one performance! For that price, one could buy a computer and watch Leontyne Price and Luciano Pavarotti on YouTube for free, forever. High ticket prices do have an impact. After the Metropolitan Opera raised ticket prices 10 percent for the 2012–2013 season, ticket sales fell over $6 million, forcing management to reverse course. That season the Met earned only 69 percent of its potential ticket sales, down from the 90-percent range decades earlier.

The fact is that many people now believe the arts to be irrelevant to their lives. Because they have been priced out of the market, they have begun to look for other, less-expensive ways to be entertained. At the same time, advances in technology have provided many new and exciting ways to be entertained—and at almost no cost. While many arts institutions argue that they need to charge high prices to sustain themselves, they violate their own missions when ticket prices become so high as to discourage the audience for the art form they profess to be supporting. One can observe the impact of such pricing whenever a high-profile arts organization offers a free event. Just about everyone shows up for free concerts, operas, and dance performances: old and young, rich and poor, black and white. The arts are not unpopular—they have simply grown too expensive.

An alternative approach to filling the income gap has been to cut back on programming, either by doing less work or less ambitious work. A ballet company might do one less program each season; a theater company might do more small plays; an opera company might reduce the number of new productions, and so on. While this is a favored strategy of many board members—especially those who do not understand why costs rise and who believe that artists are wasteful—this is a losing proposition. Audiences and donors will not continue to support arts organizations that appear to do less and less. This should be one of the take-aways from the sad demise of the New York City Opera in 2013. When that company left Lincoln Center and became an itinerant ensemble, it also drastically reduced its number of productions each season. Although these productions received strong reviews, the performances were so diffuse in time and location that the organization could not maintain its family of audience members and donors.

Arts organizations must be frugal; we have nothing to spare and cannot justify wasting donors’ contributions. But one simply cannot save one’s way to health in the arts. A dollar cut from the budget can end up costing several dollars in lost ticket sales and contributions. It is possible to lower costs in productive ways, of course. When two ballet companies share a new production, for example, they both can appear vital to their constituents without either one bearing the full cost. Finding joint-venture partners for specific projects is a positive approach that continues to bring new work to our audiences. The exclusivity of a premier is often a selling point, but audience members could care less if the same production is shared with a city thousands of miles away.

A third key strategy for filling the income gap is to seek underwriting. Such patronage historically came from the church or from royalty. As these forms of support diminished by the end of nineteenth century, the burden of support was transferred to governments, both national and local. In the twentieth century, government support became central to the life and well-being of the arts sector. In France, one percent of the national budget is devoted to the arts; even in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, qualified artists were paid a monthly government stipend.

In those countries where government support grew to substantial levels, its easy availability had several important consequences. First, arts organizations could rely on a large infusion of cash each year; artists, therefore, could afford to think big. Not surprisingly, the largest concentration of world-famous arts organizations remains in Europe—where government support has been most plentiful. To this day, European arts organizations can mount huge productions, engage important artists, commission new works, and reap the benefits of worldwide visibility. It is difficult to imagine traveling to Moscow without visiting the Bolshoi, to Milan without a trip to La Scala, or to Madrid without a sojourn in the Prado. The fame, popularity, and economic contributions of these institutions have repaid the government investment in their activities several times over. Money does not always buy quality in the arts, but predictable grants allow artists and curators to pursue their own, personal visions—greatly increasing the chances of a special product.

Those arts organizations that received large government subsidies also could afford to be more adventuresome. Without the pressure to attract private donors—or earn large portions of their budgets from ticket sales—European arts organizations, in particular, could take big risks. They could push the envelope, comfortable in the knowledge that they would receive another large subsidy the following year—even if attendance was poor or the work presented was controversial. It is not surprising, for example, that Regietheater—in which a director takes the liberty of setting an opera in a time or place not intended by the composer—began in Europe. Although this innovative approach to opera production has made its way to the United States and other nations, it remains primarily identified with the European opera houses that could afford to take great risks.

While large state-supported arts organizations prospered in this environment, it was far harder for small and mid-size arts organizations to succeed. Government funds typically went only to a few, select organizations—the state opera, the state theater, and so on. Because a culture of private philanthropy had not yet been developed, it was more difficult for an independent arts organization to become established and grow. There were exceptions, of course. Over time, several important independent organizations were formed; these groups built an audience and gained such a reputation for excellence that they were eventually awarded state support. By the end of the twentieth century, some of these smaller organizations were receiving grants at the expense of the largest institutions.

In the United States, the reverse was true. Art and government have been separated since the nation’s founding. (After all, the Puritans believed that music and dance were evil.) This situation forced private citizens who wanted the arts in their communities to provide the funds themselves. If funding had been left to local, state, or federal governments, there would be no San Francisco Opera, no Cleveland Orchestra, and no Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Although it is true that some state and local governments have invested quite heavily in the arts, apart from modest amounts granted by the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and a few other agencies, federal arts support has been limited (not counting the indirect subsidy created by the tax deductibility of contributions to eligible not-for-profit organizations).

AMERICAN ARTS PHILANTHROPY

Unlike their European counterparts, American arts institutions developed with the support of individuals, corporations, and foundations. All of these donors wanted something in return for their gifts. For many, simple recognition was sufficient. Others desired access to artists, while some sought a modicum of control of the organizations they supported. The American-style arts board—with the expectation that members will “give, get, or get off”—was a major departure from the typical European board, appointed by the government to be the steward of public funds.

At the same time that American arts philanthropy was maturing, dynamic for-profit theater, recording, movie, radio, and television industries were developing concurrently. Over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these industries grew very large, then were eclipsed by new technologies that presented and distributed entertainment in new ways. Although for-profit theater existed long before the twentieth century, for example, it flourished in the 1920s and beyond. The recording industry was born in 1877 with the invention of the phonograph. Early reco...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. America the Beautiful

- 2. To have and have not

- 3. Brave New World, Part I

- 4. Brave New World, Part II

- 5. An Alternate Universe

- Acknowledgments