- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Empires in Collision in Late Antiquity

About this book

In this book, based on lectures delivered at the Historical Society of Israel, the famed historian G. W. Bowersock presents a searching examination of political developments in the Arabian Peninsula on the eve of the rise of Islam. Recounting the growth of Christian Ethiopia and the conflict with Jewish Arabia, he describes the fall of Jerusalem at the hands of a late resurgent Sassanian (Persian) Empire. He concludes by underscoring the importance of the Byzantine Empire's defeat of the Sassanian forces, which destabilized the region and thus provided the opportunity for the rise and military success of Islam in the seventh century. Using close readings of surviving texts, Bowersock sheds new light on the complex causal relationships among the Byzantine, Ethiopian, Persian, and emerging Islamic forces.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Empires in Collision in Late Antiquity by G. W. Bowersock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Altertum. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

BYZANTIUM, ETHIOPIA, AND THE JEWISH KINGDOM OF SOUTH ARABIA

When the old antiquarian and polymath, Pliny, was registering the cities of the Near East in the fifth book of his Natural History in the middle of the first century CE, he remarked that in central Syria the great emporium at the Palmyra oasis lay between two powerful empires: inter duo imperia summa Romanorum Parthorumque (NH 5. 88). In other words, it lay between the Roman Empire and the Iranian Empire of the Parthians. Rome’s authority extended eastwards somewhat beyond Damascus, while the Parthians were in control as far west as the right bank of the Euphrates. But in the year 224 the Parthian Empire gave way to the empire of the Sassanians, who sought to revive the great Persian Empire of the Achaemenids. Only a century or so after that, Constantine moved the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome to Byzantium, which he renamed Constantinople after himself. The city was, however, soon to be generally known as the New, or Second, Rome, or simply Rome, and consequently the governors and soldiers that ruled its empire were widely referred to in the eastern Mediterranean as Romans.1 Yet, despite these colossal upheavals, the confrontation of superpowers that Pliny had so concisely formulated in the first century remained fundamentally unchanged. In the fourth century, as in the first, Palmyra, although now incorporated into a Byzantine province and home to a legionary detachment, still looked to two great empires, to the west and the east, one of Romans, or Byzantines, and the other of Iranians, now the Sassanian Persians.

Already in the third century the Sassanians had launched three devastating invasions to the west across Syria and Asia Minor. The havoc wrought by their armies left an open wound in the minds as well as the landscapes of the Romans at that time. To their military defeat was added the ultimate humiliation of the Persian capture of the Roman emperor Valerian in the summer of 260. When the Byzantine Romans took over the administration of the eastern Mediterranean lands, Persia remained as powerful a rival and threat as before, but with the conversion of Constantine to Christianity the confrontation of these two great powers was complicated by the establishment of a monotheist government in Byzantium in the face of the continuing dualism of Persian Zoroastrianism. The ambitions and animosities of both empires were accordingly reignited by religious zeal on both sides. Nature had long since dictated the main geographical area for Persia’s challenge to Rome, as Pliny had perceived. The territory at risk lay between the Mediterranean and the Euphrates River, which bounded the Sassanian realm, with its capital at Ctesiphon in Mesopotamia. This vulnerable territory in the Near East included greater Syria, Palestine, Transjordan, Anatolia, and the nascent Christian kingdom of Armenia.

The fifth century saw new and more subtle ways for the Byzantines and the Persians to challenge each other, and to win allies for their rulers and religions. The internal dissent that arose among Christians after the Council of Chalcedon in 451 greatly complicated the role of the Romans of Byzantium, although Chalcedonians and Monophysites certainly could, and occasionally did, join forces when necessary. But new opportunities for forging alliances arose in late antiquity. Both Byzantium and Persia found it increasingly effective to lend their support to client peoples in marginal areas, where the conflict between the superpowers could be played out more remotely. Alliances of this kind were quite unlike the old Roman imperial habit of propping up dependent, or so-called client, kings in tiny principalities.2 In the late antique Near East, there were tribal organizations that were partly sedentary and partly nomadic, and presided over by influential sheikhs, who could sometimes think of themselves as kings but were very different from the kings of the past.3 The sheikhs of the Jafnid clan, the so-called Ghassānids, allied themselves with the Byzantine emperor, who thereby acquired influence in Syria, Palestine, and northern Arabia according to the shifting settlements and families of the clan. The sheikhs of the Naṣrids, traditionally known as Lakhmids, forged links with Persia that brought Sassanian influence directly into the Arabian peninsula.

Even so, there had been no open conflict between the two superpowers in these regions until the Arabs of Ḥimyar, in the southwestern part of Arabia, provided the catalyst that brought in the empires of Byzantium and Persia, as well as the lesser but nonetheless expanding empire of Ethiopia as well. A surge of imperialist ambition on both sides of the Red Sea proved to be explosive, and it serves to open up an unfamiliar but immensely revealing window on late antiquity generally.4 The empire to which Ethiopia aspired in the Arabian peninsula proved a match for the expansion of Ḥimyar in that area. Both Persia and Byzantium were unable to ignore these burgeoning empires at the margins of their world. Consequently, what went on in Arabia in the sixth century had dramatic repercussions in Palestine and Syria during the century that followed, when another new empire came into being, fueled by a new religion that we know today as Islam.

Between the beginning of the third century and about 270, the pagan king (negus) of Ethiopia controlled an army that occupied parts of southwestern Arabia.5 What brought the Ethiopians there and how they were organized is unclear, as is the cause of their departure from the peninsula about 270, when the territories of Saba and Ḥimyar returned to the control of their indigenous peoples. But it was not long until what is known today as the Kingdom of Ḥimyar, with its capital at Ẓaphār, emerged out of these territories. The Ethiopians never forgot that they had been in Arabia. In the century after their departure the kings of Axum not only instituted a coinage in all three metals but arrogated titles that asserted sovereignty over places in Arabia where they no longer ruled.6 The negus represented himself as a king of kings, although there is no reason to think that he was imitating the Persian shahin-shah. The claim to be a king of kings was by no means confined to Persia, and the negus did not hesitate to be specific about the kings over whom he ruled. These were the rulers of Ḥimyar, as well as of dhu-Raydān in the Ḥaḍramawt and Saba in Yemen. He combined these empty claims to overseas sovereignty with more justifiable assertions of rule nearer home in East Africa.7

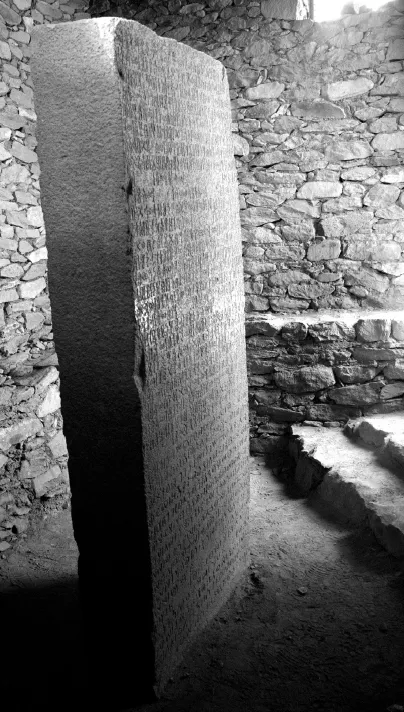

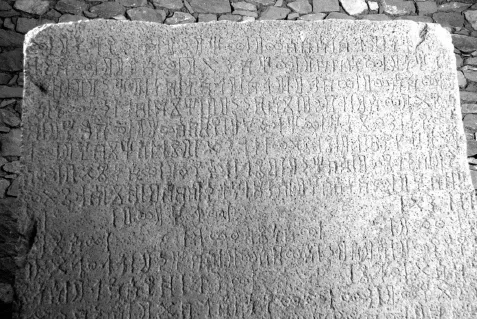

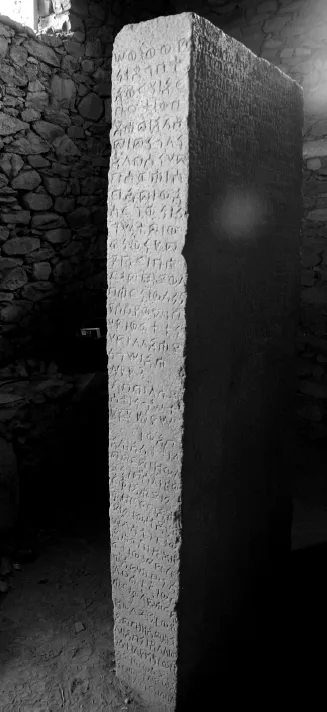

The titulature of the negus in the fourth century is known to us from the extensive epigraphy of Aezanas, or ‘Ezana, whose inscriptions allow us to follow his career in some detail. He began as a great pagan ruler, claiming to be the son of the god Ares, who was equated with the Ethiopian Maḥrem, and he ended as a devout Christian ruler who proclaimed that he owed his kingship to God. We can watch the whole process of conversion played out in the texts of his long inscriptions. The arrival of Christianity did nothing, however, to lessen the irredentist claims of the negus, even as he transferred his allegiance from Ares (Maḥrem) to the Christian God. Quite the contrary. Ecclesiastical legend, and it may be no more than this, attributes the Christianization of Axum to a certain Frumentius from Alexandria, although the actual date of the conversion of Aezanas is irrecoverable.8 The suggestion of Stuart Munro-Hay that it had already happened by 340 is not unreasonable.9 The inscriptions of Aezanas at Axum proclaimed his grandeur in no less than two languages and three scripts—Ethiopic script (left to right) and Sabaic (right to left) for Ge’ez, and Greek letters for Greek. These thereby encompassed the cultures of both sides of the Red Sea.

Stele of Aezanas discovered at Axum in May 1981, inscribed on the front, back, and right side. On the front, a text in Ge’ez (classical Ethiopic), but written from right to left in the South Arabian (Sabaic) script, and beneath that a similar text in Ge’ez, but written from left to right in unvocalized Ethiopic script, continuing on the right side. On the back, in Greek, is a comparable account of Aezanas and his achievements. Inscriptions published in Recueil des inscriptions de l’Ethiopie, vol. 1, nos. 185 bis (Semitic texts), 270 bis (Greek). Photograph courtesy of Finbarr Barry Flood.

The upper part of the front face with the beginning of the Ge’ez text in South Arabian (Sabaic) script. Photograph courtesy of Finbarr Barry Flood.

The inscriptions of Aezanas manifestly served as the inspiration for the dynamic negus of the early sixth century, Ella Asbeha, known as Kālēb. The Christianity that he inherited is fully developed in the preamble to a text he caused to be inscribed in Ge’ez, but in the Sabaic script: “To the glory of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.”10 By the time of Kālēb, Christianity had put down solid roots in Axum. In laying claim to overseas territories that he did not actually rule, Ella Asbeha/Kālēb thus resumed the tradition of Aezanas whose inscriptions he so obviously imitated. As Kālēb’s claims became increasingly strident, they were matched by social and political upheavals across the water in Ḥimyar that gave him precisely the opportunity he needed for overt intervention. He was now in a position to propel the Axumite regime to realize its claim to Southwest Arabia. How, we must ask, had all this come about?

Ethiopian imperialism in the sixth century depended upon a great change that had, curiously, taken place in Ḥimyar in the late fourth century, exactly when Aezanas had begun to proclaim openly his conversion to Christianity. This had led him to assume a more aggressive public stance towards the Arabian territories. Like Aezanas, the king in Ḥimyar at that time also adopted a new religion. But, fatefully, it was not the same religion. What happened on either side of the Red Sea reflected both the old and the new territorial claims of the two kingdoms. The religious conversions they each underwent ultimately delivered the spark that set off an international conflagration.

Just as news of the territorial boasts of the negus reached the Arabian peninsula, news of his conversion from Ethiopian paganism to Christian monotheism must also have arrived there. Of course South Arabia had encountered monotheism before through Jewish communities in the Ḥaḍramawt and possibly by way of Jewish immigrants from Yathrib in the north.11 So what happened in Axum would not have been altogether incomprehensible to the Ḥimyarites, even if they lacked any deep understanding of Christian doctrine or Christian sectarianism. The kings of Ḥimyar, who had taken over all the grandiose titles of the Ethiopian kings, suddenly, remarkably, and inexplicably also became monotheists themselves. But their monotheism was Jewish.12 This extraordinary development, so closely following the changes in Ethiopia, is amply documented in the Sabaic epigraphy.

The right side of the stone, with the continuation of the text in unvocalized Ethiopic script. Photograph courtesy of Finbarr Barry Flood.

In fact, the history of Southwest Arabia has largely been written from its inscriptions, which fill the gaps in the literary record from the fourth century onwards, when Aezanas arrogated such Arabian titles as king of Ḥimyar, Saba, dhu-Raydān, Tihāma, and Ḥaḍramawt. The pretentions of the negus had not passed ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1. Byzantium, Ethiopia, and the Jewish Kingdom of South Arabia

- 2. The Persian Capture of Jerusalem

- 3. Heraclius’ Gift to Islam The Death of the Persian Empire

- Notes

- Index

- The Menahem Stern Jerusalem Lectures