- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

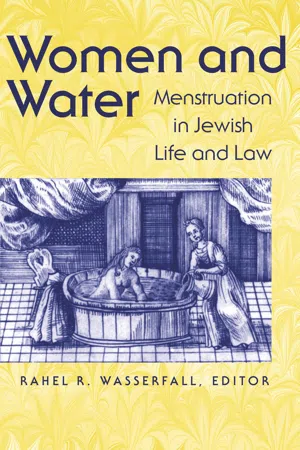

The term Niddah means separation. During her menstrual flow and for several days thereafter, a Jewish woman is considered Niddah -- separate from her husband and unable to practice the sacred rituals of Judaism. Purification in a miqveh (a ritual bath) following her period restores full status as a wife and member of the Jewish community. In the contemporary world, debates about Niddah focus less on the literal exclusion of menstruating women from the synagogue, instead emphasizing relations between husband and wife and the general role of Jewish women in Judaism. Although this has been the law since ancient times, the meaning and practice of Niddah has been widely contested. Women and Water explores how these purity rituals have affected Jewish women across time and place, and shows how their own interpretation of Niddah often conflicted with rabbinic views. These essays also speak to contemporary feminist issues such as shaping women's identity, power relations between women and men, and the role of women in the sacred.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Women and Water by Rahel Wasserfall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Brandeis University PressYear

2015Print ISBN

9780874519600, 9780874519594eBook ISBN

9781611688702PART I

The Historical Context

This section opens with a short history of the laws of Niddah. In her contribution, Meacham sets the stage and describes the context in which the laws of Niddah and the challenges to these laws have evolved. Fonrobert and Cook then discuss a fundamental historical moment in Jewish history, the emergence of the rabbinic culture. This process took shape in the midst of a political and cultural disaster that followed the destruction of the Second Temple. The early rabbis had to make sense of this historical and cultural catastrophe.

The rabbinic literature includes the Mishna (the teaching) and the two Talmuds. The Mishna was compiled by Rabbi Judas the Nasi in 215 C.E. The Mishna is an arrangement of rabbinic law, including the written collection and the oral tradition of the past several generations. The Babylonian Talmud and the Palestinian Talmud (Jerusalem Talmud) are commentaries on the Mishna. The Palestinian Talmud was edited in 380 C.E. Much of its material serves as the basis for the Babylonian Talmud, which was finished and edited in 499 C.E.1

Cook presents that moment in which Israelites had to transform Judaism after the catastrophe of losing the Temple as the focus of identity and ritual. She argues that the early rabbis had to build new meanings for their new position without the Temple. Cook contends that the ritual of niddah was used as a way to connect women to God, to transcend their biological nature. Niddah becomes a sort of covenant with God in this early and difficult period of historical destruction.

Fonrobert takes us a step forward when she follows the talmudic rabbis (300–600 C.E.) and shows how they invented a new science and expertise of menstrual blood. She departs from Cook by stating that in this process women’s authority and self-control were lost, at least in the texts. The displacement of women themselves as authorities over their own bodies is the focus of her rereading of the Yalta story. For Fonrobert, Yalta’s story is a particular focal point in which the underlying contestation of rabbinic gender politics emerges to the textual surface. The rabbis historically became the experts on menstrual blood, but this did not come without contestation, as we will see in Cohen’s essay on the medieval context.

Although the rabbis successfully established themselves as experts in niddah, women during the subsequent centuries may not have accepted the rabbis’ authority easily. Cohen presents some historical moments in which women’s whispers can be heard through the rabbis’ voices. We learn that women in Maimonides’ Egypt (1135–1204) may not have accepted that their practices were less legitimate and that they were less “religious” than the rabbis. In seventeenth-century Europe, according to Storper Perez and Heymann, older women may well have taught younger women different practices from those required by the rabbis. In both essays we can sense the existence of women’s culture and women’s friendship struggling to define women’s experience from their own point of view. This women’s culture seemed to receive a strong blow when the rabbis’ authority converged with the establishment of medical authority in the eighteenth century. Women’s bodies became the subject of a new science, and women again lost control over their own bodies.

Koren, in her exposition of thirteenth-century kabbalist views, takes another course, focusing not on the contentions but on the new rationalization given to the laws of niddah by mystics. The sixth-century text Baraitadi-Niddah, which presents menstruation as an abomination and the source of much human suffering, became incorporated into Ashkenazic practice by the thirteenth century.2 Faced with the laws regulating purity and sexuality, the kabbalists had to make sense of them. They presented these laws not only in terms of “the lower world” (relations between the genders) but in terms of a theurgic struggle in the divine unity itself. Menstrual impurity could empower the demonic other side.

The essays in this section span many centuries, each providing a glimpse into a world of Jewish practices and belief systems. These are in part echoed in today’s Jewish world, for example, the belief that a child born without miqveh is a bastard (mamzer) (Koren) and the practice of bathing at the end of the seven days of whitening without dipping in the miqveh (Cohen).

NOTES

1. J. Gribetz, The Timetables of Jewish History (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993).

2. J. D. S. Cohen, “Menstruants and the Sacred in Judaism and Christianity,” in Women’s History and Ancient History, ed. S. Pomeroy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991).

Tirẓah Meacham (leBeit Yoreh)

An Abbreviated History of the Development of the Jewish Menstrual Laws

Chapter 15 of Leviticus serves as the basis for the Jewish menstrual laws. The Hebrew term used for menstruation in Lev. 15:19, 20, 24, 33 is niddah, which has as its root ndh, meaning “separation,” usually as a result of impurity. It is connected to the root ndd, “to make distant.” Later, but still within the biblical corpus, this meaning was extended to include concepts of sin and impurity. The Aramaic Bible translations (Onkelos, Pseudo-Jonathon, and Neofiti) use the root rhq, “to be distant.”1 Both roots reflect the physical separation of women during their menstrual periods from physical contact or from certain activities in which they would normally engage at other times.

Separation because of menstruation had both public and private aspects. Because of the prohibition against entering the Temple in a state of ritual impurity, this manifestation of female physiology clearly limited cultic contact for women of childbearing years, which in turn served as a factor determining female status in a patriarchal environment. In the private sphere, food or objects that required a ritual state of purity could not be touched by menstruating women without becoming contaminated or made unfit for priestly consumption. Touching a menstruating woman yielded impurity until sunset. Touching what she sat or lay on contaminated the person, who was then required to bathe and wash his clothes and was impure until sunset. Coitus transferred to the man the entire seven days of impurity, as well as the power to contaminate (Lev. 15:24). In Lev. 18:19, the people of Israel are enjoined not to approach a woman sexually during her separation. In Lev. 20:18 coitus with a menstruant is forbidden, carrying the punishment of karet, excision from the Jewish people. Modern Orthodox practice is based on a harmonistic reading of these three chapters and of Leviticus, chapter 12. The destruction of the Temple put many purity laws in abeyance. Menstrual laws, however, remained in force and became more restrictive in the private sphere, chiefly in areas concerning physical separation from one’s spouse and internal examinations.

The verses dealing with women must be understood both in their own context and in the context of the larger legal system. We will begin with an examination of Leviticus, chapter 15, which covers several topics: verses 2–15 state the laws concerning a zav, a man with an abnormal genital discharge, often (and probably correctly) translated as gonorrhea; verses 16–17 deal with a man who ejaculates semen; verse 18 refers to semen impurity due to coitus; verses 19–24 state the laws concerning menstrual impurity; verses 25–30 concern a zava, a woman with a uterine discharge of blood not at the time of her period, or as a result of a prolonged period.2 Each of the five sections in the chapter describes the type of genital discharge. For the male, in the case of the zav, the reference is to mucus-like discharge from a flaccid penis (according to rabbinic interpretation) and to normal ejaculate for other men. In the case of the female, the reference is to a discharge of blood from the uterus with no distinction between the abnormal blood of the zava and the normal menstruation of a niddah. Each section also prescribes the length of time the impurity lasts and objects that are subject to that impurity. The zav and the zava must count seven clean days after the abnormal genital discharge ceases. The zav must bathe in “living waters” (a spring or running water). Both must bring a sacrifice. For normal male seminal discharge and contamination by semen during coitus, a purification ritual is prescribed that includes bathing and waiting until sunset. For normal menstruation, only a waiting period is prescribed in the Bible, though bathing is part of the purification ritual for those who have been contaminated by the menstruating woman or who have touched the objects she contaminated. Such bathing and laundering of clothes is required for the person contaminated by the niddah or the zava.

Leviticus 15 has an obvious chiastic structure (A-B-B′-A′) in which the verses dealing with abnormal male discharge (A) are followed by those concerned with normal male discharge (B). V. 18 serves as the intersection point where male and female genitals meet (become one flesh, basar ehad in Genesis 2) in coitus.3 Normal menstruation serves as B′, while abnormal uterine bleeding, A′, ends the section. This structure suggests that there is more in common between these male and female discharges than the fact that the discharges are from the genitals and cause impurity. This is the most intense concentration of verses dealing with reproductive organs in the Bible. It is clear from the terminology that in the case of the normal male the text is referring to semen, zerʿa, while in the case of the female the discharge is blood, dam.

To understand more fully the connection between semen and blood, we must turn to Leviticus, chapter 12, which deals with birth impurity. This chapter also uses the concept of niddah and the laws mentioned in chapter 15 as a reference point. The text refers to conception as a very active female process, “female semination.” Verse 2 of this short chapter may be translated: “A woman who seminates (tazriʿa) and gives birth . . .” The chapter goes on to delineate the laws of separation after birth,4 the blood of purification, birth sacrifices, and the purification ritual in the Temple. The time of ritual impurity after a birth is likened to niddah. Following this is a time during which any blood seen does not cause ritual impurity. The blood during this period is called dam tohar, blood of purification. Tazriʿa, which I have translated as “seminated,” is the causative form of the root zrʿ and also the root of the word zerʿa, semen, mentioned in chapter 15. The Aramaic translations use the root ʿadi, “to be pregnant, carry.” The best of the manuscripts of the Aramaic translation attest to an active form of this root, meaning “to give off seed.”5

The idea that menstrual blood and fertility are connected is found in several midrashic sources and in the tannaitic material.6 In Mishnah Niddah 9:11, R. Yehuda connects virginal blood and menstrual blood to fertility: “R. Yehuda says: ‘Every vine [woman] has wine [menstrual and virginal blood] within her. But one which does not have wine [menstrual and virginal blood] within her—she is dorqetei [infertile].’ ” In Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Niddah 64b records the statement of a sage of the tannaitic period, R. Meir, who makes a very positive connection between blood and fertility: “Each woman whose [menstrual and other] blood is great, her children are numerous.”

Despite some modern interpretations by biblical scholars, anthropologists, and feminists viewing menstrual laws as a taboo system, it is likely that Leviticus, chapter 15, is, in fact, a medical or scientific chapter in the Bible, dealing with ideas of seed and seed impurity. Uterine blood was seen as female seed, the parallel to male semen. This idea was quite widespread in the ancient Near East and is clearly stated in the Greek medical texts, in Aristotle, and in later Roman texts.7 The idea itself is an attempt to explain female physiology on the basis of a male paradigm. Males ejaculate seed. Females menstruate when they are not pregnant but not during pregnancy. Menstrual blood must therefore be the female contribution to conception. The paradigm, of course, loses its coherence when one tries to correlate female orgasm, conception, and menstruation, but it was one fairly logical model of reproduction available in antiquity. Only when ovulation came to be understood in the nineteenth century could female fertility be separated from menstruation and female sexuality.8

The difference in seed impurity between males and females essentially reflects differences in male and female physiology. Male ejaculation is completed quickly, and the semen is generally either deposited in a woman’s body or absorbed by clothing, bed covers, or some other material. This would account for the short duration of the impurity—until nightfall. Irregular loss of seed or seedlike substance, as in the case of the zav, is more complicated because it is lost not by ejaculation but by slow oozing from a flaccid organ. This, in fact, makes it much more like female discharge. Abnormal male discharge and normal and abnormal female discharge progress over a period of time, none of them having an exact moment like ejaculation that marks the discharge. Therefore, they are apt to be deposited on a variety of places and types of furniture.

The difference between the niddah a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Menstrual Blood into Jewish Blood

- I. The Historical Context

- II. The Ethnographic and Anthropological Tradition

- Appendix

- Glossary

- Contributors

- Index