- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A History of the World in Sixteen Shipwrecks

About this book

Stories of disasters at sea, whether about Roman triremes, the treasure fleet of the Spanish Main, or great transatlantic ocean liners, fire the imagination as little else can. From the historical sinkings of the Titanic and the Lusitania to the recent capsizing of a Mediterranean cruise ship, the study of shipwrecks also makes for a new and very different understanding of world history. A History of the World in Sixteen Shipwrecks explores the age-old, immensely hazardous, persistently romantic, and ongoing process of moving people and goods across the seven seas. In recounting the stories of ships and the people who made and sailed them, from the earliest craft plying the ancient Nile to the Exxon Valdez, Stewart Gordon argues that the gradual integration of mainly local and separate maritime domains into fewer, larger, and more interdependent regions offers a unique perspective on world history. Gordon draws a number of provocative conclusions from his study, among them that the European "Age of Exploration" as a singular event is simply a myth: over the millennia, many cultures, east and west, have explored far-flung maritime worlds, and technologies of shipbuilding and navigation have been among the main drivers of science and exploration throughout history. In a series of compelling narratives, A History of the World in Sixteen Shipwrecks shows that the development of institutions and technologies that made the terrifying oceans familiar and turned unknown seas into well-traveled sea-lanes matters profoundly in our modern world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A History of the World in Sixteen Shipwrecks by Stewart Gordon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia militar y marítima. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

DUFUNA DUGOUT

In May 1987, a Fulani herder in northeastern Nigeria was digging a new well. At a depth of sixteen feet he struck something hard and quickly realized that this was no rock, but something large, wooden, and likely old and important. First local, then state, and finally national officials visited the site just outside the village of Dufuna, located on the seasonally flooded plain of the small, often-dry Komadugu Gana River, about two hundred miles east of Kano.1 Carbon dating of a wood fragment identified whatever was buried there as eight thousand years old. Nigeria did not, however, have the resources to fund an excavation. Fortunately, a local archaeologist named Abubakar Garba, from the University of Maiduguri, formed a partnership with a German team from the University of Frankfurt headed by Peter Breunig.2

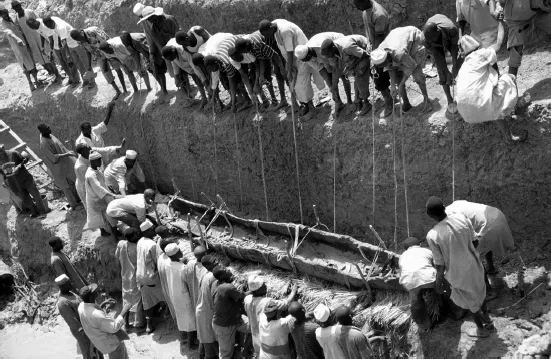

In 1994 the team uncovered and photographed a fully intact boat, lying upside down. It is almost thirty feet long, carved from a single log a foot and a half in diameter, with sides and bottom two inches thick; it is missing only a few small pieces along the top edge. Elegantly designed, the boat features long rising tapers at both the bow and stern. It is made of African mahogany, likely either Khaya grandiflora or Khaya senegalensis, both of which grow in drier conditions than the typical rain forest habitat of the other two mahogany species. Mahogany is quite suitable for boats. It is dimensionally stable, survives well in water, and resists rot because the tree synthesizes and infuses phenol (carbolic acid) into its wood, which kills rot. The elegant design of the Dufuna boat suggests a long and well-developed boatbuilding tradition, not a recently acquired skill.

The boat was exposed and photographed. The team did not turn the boat over, so they could not see possible evidence of the use of fire or an adze in its construction. The Dufuna boat was initially reburied, to safeguard it until funds and facilities for full excavation and long-term preservation became available. The German-Nigerian team re-excavated the boat in 1998 and moved it to a purpose-built conservation building in Darmaturu, the capital of Yorbe State. They placed the dugout in a vat of polyethylene glycol, the standard procedure for stabilizing ancient wood. The slow process by which PEG penetrates the wood and fills the cells is now complete, and as of 2014 the boat is ready for the gradual drying process, which must take place under carefully controlled conditions. The unstable political situation in Nigeria has prevented the team from beginning the drying process.3

Local men lift the Dufuna boat from the excavated pit.

PHOTO COURTESY PETER BREUNIG

Today, satellite photos show no agriculture and little settlement outside the floodplain of the Komadugu River. Both north and south of the river are miles upon miles of scrub desert, which in years with some rain supports herding. In the time of the Dufuna dugout, however, this region was a very different place. Lake Chad, now some two hundred miles to the east, was much larger, its shoreline perhaps only thirty miles east of the Dufuna site. It is even possible that the Dufuna site was a lagoon that connected to Lake Chad. It is not difficult to imagine the Dufuna boat’s ordinary uses for fishing, crossing the Komadugu River, carrying gathered food plants, and visiting other settlements in the lagoons and on the shoreline of Lake Chad. None of the excavated sites east of Lake Chad have yielded evidence of agriculture or domesticated animals. The Dufuna people likewise probably depended on fishing, hunting, and gathering. Equally likely the canoe would have carried men to war against rival groups in the region. Unfortunately, even though the site is well stratified by seasonal flooding, no artifacts or direct evidence of these activities have so far been discovered.4

Dugouts in a Post–Ice Age World

Dated to about the same time period as the Dufuna canoe, similar dugout craft have been uncovered by archaeologists in Europe. For example, construction workers found a dugout in a peat bog near the town of Pesse in Holland. Currently housed in the Drents Museum near the find site, the canoe is about as unsophisticated a small boat as one can imagine. The builders merely hollowed out a Scotch pine log nine feet long and a foot and a half in diameter. There was no attempt to shape the bow or the stern. Several archaeologists doubted that such a crude craft could even be paddled. A reproduction of the Pesse dugout, however, proved to be both maneuverable and relatively stable.

Just as the Sahara was a very different place eight thousand years ago, so was Europe. Vast amounts of water had been tied up in the glaciers of the last ice age (at its maximum extent about twenty thousand years ago), which covered Holland, northern Germany, Scandinavia, and England. The sea level had dropped four hundred feet. As the glaciers retreated (about ten thousand years ago) they left behind newly cut lakes and much-changed river drainage. It was a time of marshes, bogs, and eventually large forests. Travel by river and across marshes probably spurred development of simple dugouts as humans recolonized the north European plain. Linden trees were suitable, common, and the most frequently used material for the oldest European dugouts. Archaeologists have excavated dugout boats across much of Europe in the period following the last ice age, for example in Stralsund, Germany (7,000 years old), Noyen-sur-Seine, France (7,000 years old), Lake Zurich, Switzerland (6,500 years old), and Arhaus, Denmark (5,000 years old).

In the north of what is today the United States, conditions were similar to post–ice age Europe: bogs, marshes, lakes, many rivers, and developing forests. The earliest finds of dugout canoes in North America date from the same period, roughly five to six thousand years ago.

The point of this discussion of various ancient dugout finds is that there was no diffusion of dugout technology from one broad region to another.5 It now seems certain that the dugout was invented in many different places in response to local needs, such as fishing, migration, transport of materials, and coastal and river trade. Cultures experimented until they found the best available trees.6 What tied these early boats into a “world” was not communication between peoples using them but common problems and solutions of material, production, design, and use.

How to Make a Dugout

A small dugout requires a tall, straight tree with fifteen feet of usable trunk at least thirty inches in diameter. The fewer knots the better. Ecological conditions of deserts, Arctic regions, and high mountains rule out such trees. On the steppe and plains, dugouts could only appear if one of the few native trees proved suitable. Nevertheless, the rest of the world offered a variety of species suitable for dugouts. It seems logical to assume that experimentation over millennia arrived at the best local trees for dugout canoes. In eastern North America white pine found favor in the north, while cypress dominated the south. On the Pacific Coast, Sitka spruce, redwood, and Douglas fir worked. In Northern Europe, linden was the preferred wood. Tropical forests offered a plethora of tall straight trees that formed the overstory of the rain forest.

An understanding of why ancient dugout makers found these particular woods desirable requires a short discussion of the physics and chemistry of trees. Trees are essentially complicated vertical piping—that is, long pores move nutrients from the soil up, and other pores shunt energy down. Some trees have large pores (oak, for example), producing prominent grain when the wood is cut. Other trees, such as pine and maple, have tiny, almost invisible pores. Only the outside inch or two of a tree contains active pores, which move nutrients and energy. The entire trunk inside this active zone is dead and merely provides support for the branches and leaves of the crown of the tree.

The bonding material that joins the long vertical pores gives wood its strength. Heavier wood means stronger bonding material. Tight bonding between pores was particularly important for the two ends of the dugout. Tapering these two vulnerable areas left less bonded wood than the sides or bottom. If either end dried unevenly, the boat would split. Over millennia, boatbuilders must have experimented with locally available trees to find the few that were light enough and strong enough to serve as dugouts. They also discovered that a few trees, such as cypress and mahogany, had properties that resisted rot. The best dugout canoe, therefore, came from a big, straight tree with few lower branches (therefore, no knots), which contained relatively small pores, was strong enough to resist splitting in the fore and aft, but was not so heavy that the boat sat dangerously low in the water. Dugouts must be made from green, living wood. Dry, fallen logs have usually shrunk and checked (cracked along the grain) so badly that they could never be structurally sound or waterproof.

The first problem was how to fell the tree. A controlled burn at the base of the tree was much more efficient that trying to cut it down with flaked stone tools. Dugouts from across the world show traces of controlled burn, so the technique must have been invented in numerous cultures at different times and places. The canoe carvers probably learned early that once the narrow layer of green wood under the bark had been cut away, the old wood underneath would burn quite readily. The carvers would have kept the tree wet above the burn area.

Once felled, the tree was almost certainly worked before it was moved. A fifteen-foot section of freshly cut pine, thirty inches in diameter, weighs more than a ton. After the log’s interior was burned and scraped away to a remaining two-inch wall, and a bow and stern shaped, the canoe would weigh only about two hundred pounds. Making the boat in a harder, denser wood than pine might add another fifty to seventy-five pounds to the finished weight. This weight would have been quite movable from the felling site to the water.

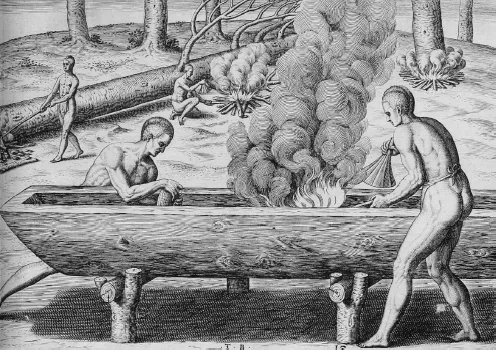

Turning a trunk into a dugout required only the simplest of tools. Repeated controlled burns followed by scraping gradually removed the heartwood, leaving the outermost few inches. This process can be done without even a hafted scraper or cutter. Relatively unsophisticated scrapers will do just fine. They need not even be of particularly hard stone. A clamshell or fire-hardened wood will suffice, as long as there is plenty of material nearby, as these relatively soft tools wear out quickly. A few sites of ancient dugout canoes have yielded not only boats but also the many clamshells used in hollowing them out. Cultures that possessed better tools, particularly metal tools, could fell the tree and hollow out the trunk for a dugout without fire. The sequence probably began with chopping down the tree with primitive axes. Next the log was split with wedges. Lastly the dugout was hollowed out with chisels or adzes.7

The burning of the inside of a dugout canoe by Native Americans in sixteenth-century Virginia, from Theodore De Bry, Der Ander Theyl (Manheim, 1590).

Until recently, archaeologists had speculated that ancient dugouts would take months or even a year of work by a group of skilled boatbuilders. These archaeologists argued that such boats were a significant investment of a group’s capital and therefore required some degree of social organization. Experimental archaeologists, in contrast, have used reproductions of ancient tools made from locally available materials to burn and scrape a serviceable craft from local trees. In several experiments in different countries they have found that a typical small dugout takes only the labor of a week or two by a small, relatively unskilled group.

Limitations of Dugouts

Even optimal local wood dugouts had several intrinsic limitations. First, of course, was size. They could be no larger than locally available tree trunks. Second, they were relatively heavy and not suitable for long portaging. They tended, therefore, to be made and used locally. In the larger picture, trade in such boats tended to follow rivers.

The third limitation was in the nature of solid wood, which tends to split along the grain if allowed to dry out. Areas where the wood is sheared across the grain, typical of the bow and stern of dugouts, are especially prone to splitting. Dugouts were best kept in the water. Dugout builders figured out that the safest place to store the boats against winter damage was on the bottom of a river or shallow bay, below the ice and away from winter storms. Several ancient archaeological sites in Europe have yielded boats filled with stones, still in winter storage after millennia.

Dugout builders faced yet another limitation: the round bottom of the boat, which made it relatively unstable and prone to capsizing. In many places around the ancient world, dugout builders realized that the hollowed-out tree could be opened with heat, wedges, and cross-braces, yielding a flatter, wider contour and a more stable boat. Such a process precluded a solid wood bow and stern. Dugout builders, therefore, generated a variety of designs, which attached supplemental wood to cover the opened log at the bow and stern. Unfortunately, the process of widening the dugout for stability did not solve another critical problem of design, the dugout’s minimal height between the surface of the water and the edge of the log (known in maritime terminology as the “freeboard”). Waves of any size could throw water into the dugout. This was not a problem on rivers, marshes, small lakes, or close to shore, but open-water ventures required modified design. One solution was to add a plank at the top of the log to increase freeboard. Producing such a plank, however, required metal tools to cut and shape it. The second solution to low freeboard was to attach two hulls together, which produced a stable, seaworthy craft capable of long open-water voyages.8 It is to the long history of the marvelous outrigger dugouts of the Pacific that we now turn.

Dugouts of the Pacific

The history of dugouts of the Pacific begins on mainland Southeast Asia, whose colonization was an integral part of waves of early human migration from Africa into Asia. The timing and details of these migrations are much disputed. Archaeologists have found stone tools in several sites on mainland Southeast Asia, but the earliest direct evidence of modern humans is a recently found partial skull from a cave in Laos, dated between 58,000 and 43,000 BCE.9

The earliest direct evidence of modern humans in island Southeast Asia comes from human bones on the island of Palawan in the southern Philippines (43,000 BCE) and from another site in Borneo (40,000 BCE). With a lower sea level in this period, land bridges may have connected the mainland and some of what are now islands. There is, however, strong evidence of early open-water crossing from Southeast Asia to Australia. The remains of the first settlements of aboriginals on the Cape York Peninsula consistently date to about 48,000 BCE. These early explorers could only have come across the Torres Strait from New Guinea, traversing perhaps sixty miles of open water. None of these early sites, however, have yielded remains of boats or rafts, causing some archaeologists to speculate that a tsunami might have ripped a whole chunk of land, perhaps a matted mangrove swamp, off New Guinea and floated it across the Torres Strait. The sites on the north coast of Cape York suggest an initial population of a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Copyright

- Introduction

- 1. Dufuna Dugout (c. 6000 BCE)

- 2. Khufu Barge (2600 BCE)

- 3. Uluburun Shipwreck (1327 BCE)

- 4. Sutton Hoo Burial (c. 645 CE)

- 5. Intan Shipwreck (c. 1000)

- 6. Maimonides Wreck (1167)

- 7. Kublai Khan’s Fleet (1281)

- 8. Bremen Cog (1380)

- 9. Barbary War Galley (1582)

- 10. Los Tres Reyes (1634)

- 11. HMS Victory (1744)

- 12. Lucy Walker (1844)

- 13. Flying Cloud (1874)

- 14. Lusitania (1915)

- 15. Exxon Valdez (1989)

- 16. Costa Concordia (2012)

- Conclusion: Maritime History as World History

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index