- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

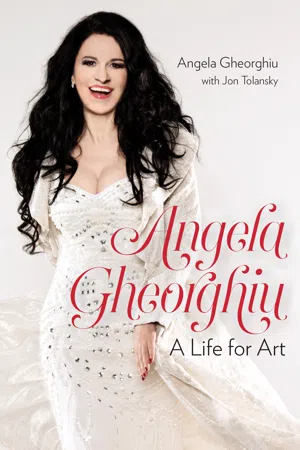

Angela Gheorghiu is one of the most passionate and talented artists working in opera today, a larger-than-life figure whose intensity and drive, on stage and off, have commanded the attention of the opera world. Largely composed of exclusive interviews with the artist, this authorized biography of the internationally acclaimed soprano, covers Gheorghiu's life and career from her childhood in Communist Romania to her spectacular Covent Garden debut in 1992 and up to the present day. In it, Gheorghiu shares new insights into the performance of many of her iconic stage roles and her collaborations with opera's leading lights. Also featured are commentaries and reminiscences by such celebrated figures in the music and art worlds as Grace Bumbry, José Carreras, Plácido Domingo, Marilyn Horne, Bryn Terfel, and Franco Zeffirelli.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Angela Gheorghiu by Angela Gheorghiu in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Música. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Poems of Childhood

You were born in 1965, a year in which Romania was going through a time of great change.

I came into the world in a time of hope, at the beginning of September 1965. Romania had been out of the domination of Soviet troops for several years now, the wartime wounds were beginning to heal, and, in Bucharest, the Communists had elected a new leader in whom, at least for starters, everyone placed high hopes.

At the time of my birth, my parents were already living in Adjud in a big and beautiful house with six rooms in the new area of town, which we all used to call “the neighborhood.” But Ion and Ioana Burlacu were both originally from Adjudu Vechi, a nearby village, and before moving to “the neighborhood” it was in Adjudu Vechi that their romance had begun.

In the countryside, the people’s greatest joy was to attend the hora, the local folk dance event. There, each time, my mother went chaperoned by her own mother, as girls were not allowed to go unaccompanied. The youngest of five siblings, Ioana Sandu was very loved, protected, and pampered.

As she was very beautiful, my mother was intensely courted by the village lads. With dark brown hair and green eyes, she was getting a lot of attention. She was also very elegant and always dressed in clothes she had cut and sewed for herself, because she had solid tailoring training with the merchants in Adjud.

She used to make clothes not only for herself, but also for the village girls, for whoever asked her. There were nice clothes, cut from good fabrics, chosen with impeccable taste. Whenever she helped out her friends with her skills, she never asked for any money. Seeing her seriously inclined toward tailoring, her eldest brother gave her a Singer sewing machine—specifically for her to use later on, if she ever decided to become a professional seamstress.

Do you still have this sewing machine?

Yes, I still have it, now it’s just a nice piece of antique furniture, but I have kept it carefully.

How was Ion Burlacu back then?

My father was six years older than my mother. He was a charming man, intelligent and ambitious, with a penchant toward poetry and a passion for flying.

Were there siblings in his family?

He was the second of six. He attended the Vocational School CFR,* and initially wanted to become a pilot. But a career in aviation would have meant too many years of school and a service that would have led him away from home and his family. Also, in those times, the elder brothers had a great unwritten duty to begin work early so that they could help their parents and younger siblings.

So his decision to abandon aviation was not really what he wanted?

Grandma Victoria, my father’s mother, used to tell us how she had begged my father, tears in her eyes, to stay home after the war and get a job at the newly established railway company CFR Adjud, as the town had recently become an important railway junction. Serving an apprenticeship as a fireman on a steam engine for a year and four months was very tough.

According to Grandma, Dad would come home from work all black and greasy. He later managed to apply to the train drivers’ school in Iași,† and once his studies were completed, he returned to work in Adjud with a new status. As a driver in uniform he belonged to one of the few categories of “working people” who were rewarded with good wages for hard work.

They had the same special treatment as the miners. . . .

Yes, railway workers and miners were part of a special wage category, receiving much more than teachers, for example, but it is true that their work was very demanding.

Coming back to the dance events in the village, my mother must have been very impressed with my father, who is to this day a very garrulous person. In Adjudu Vechi, compared to all the other lads of the village, he stood out. The time he had spent in various towns provided him with an unparalleled life experience. He was educated, handsome, with curly hair and merry eyes, and moreover—as per the secret dream of all girls at that time—he had a hat, a uniform, and a bicycle: three criteria that would have endeared him in the eyes of any adolescent.

Have you kept photos from that time?

It so happens that I have, indeed, some photos of my mother from that time. They were made by a team of journalists and photographers from a Russian magazine. The Russians were keen to present the beautiful villages and towns in the Communist countries in their publications, and those journalists wrote a feature about Adjud and the Siret River Valley.

My mom and Tănţica, a friend of hers, were chosen as models for the photo shoot to accompany the story. As Mother used to make the clothes for both herself and her friend, they may have seemed the most stylish girls in the village. This is how, right after the war, my young mother had a genuine, avant la lettre photo session.

So both your mother and father were, each in their own way, quite some characters in Adjudu Vechi. How did the grandparents view their relationship?

My maternal grandfather, Ilie Sandu, did not attend the meeting with my father and his parents.

A fairly radical gesture. . . . But why?

When Dad came with them to ask for my mother’s hand in marriage, to state his serious intentions about her, Grandpa did not accept him—there was something about him that he did not like. Maybe he thought he had a malicious or arrogant air. . . . Maybe it was just instinct. . . . Maybe he knew his family, we would never know. It was hard to not like my father, but my grandfather had his vast experience with people and he judged my father through this. Quite harshly, I’d say.

Grandma Sanda Sandu, on the other hand, would have agreed with everything my mother wanted—“As you wish, dear,” were her words. As for my mother, she was adamant: she told her parents that she only wanted Ion, otherwise she would go to the monastery. And so it was. Ioana and Ion were married in 1962.

Did your maternal grandfather accept Ion Burlacu eventually?

Yes, sure. Even though he had objected before the wedding, my grandfather did not hesitate to help my parents after they had become a family and moved to Adjud. A mason by profession, he built the house, while my father’s parents, Constantin and Victoria Burlacu, bought the land. Each side of the family had its own contribution. All were extremely hard workers and loved us enormously.

Therefore, courtesy of our grandparents, our home in Adjud was very large and very well made.

This was something quite unusual at the time, when people were building small houses both for lack of money and also for fear that they would not be able to keep them warm, or maintain them in general.

Our house was really big. We had no fewer than six rooms, plus a separate kitchen, a storeroom, and a cellar. We had a lot of space, every room was big, everything was built with love. In summer, we would spread out and take over the entire house while in winter we would gather in only two or three rooms, so we could warm them up.

Having spent my childhood in such pampering conditions also created some problems for me later on. When I went to boarding school in Bucharest, as I was not used to living in small spaces, I thought I would suffocate.

Not only our home, but the entire neighborhood where I grew up was new. It was known as the railwaymen neighborhood and had developed in just a few years because, with the establishment of the railway junction in Adjud, a lot of new jobs were created and many people from the neighboring villages had come to settle in town.

For all of them, moving to the town was a logical move, as commuting was more a question of luck. At that time there were no buses, no public transportation, so the people had to march to the town or hitchhike with a horse-drawn cart—that is, if they were lucky to find one. The time and effort spent, at each beginning and end of day, were huge. And also huge was the difference between the villages and the town. For all railwaymen, as for my parents, this move was a sign of progress, a step forward.

Times were not easy, certainly, but in those early years we had everything we needed, because we were living in a house on a plot of land and we could be self-sufficient. Around the house, my mother worked in no fewer than four gardens—one with vegetables, one with living birds, a little vineyard, and the front yard, which was full of flowers. All were my mom’s work.

How did she have time to do everything? Did she also have a job?

No. Despite all her rigorous tailoring training made with the Jews of Adjud, my father did not allow her to take a job. Such were the times, such was my father’s judgment. . . . In the railwaymen neighborhood, in most families, things were pretty much the same, and if Mother had wanted to do something differently, like earning money by sewing clothes for others, people would have noticed and frowned upon it.

From the time of the marriage to the birth of the first child, three years went by.

In the early years of her marriage, besides the household chores, Mother struggled to give birth to a child, but without any luck. After several unsuccessful attempts, when my time came, Mom had to stay in bed and take injections in order to make sure she could carry me to the term.

I was the first born after three hard years of failed attempts. A much awaited, much loved child. Mother did everything she could so that the pregnancy was successful. A year and four months later, when my sister was born, Elena, she had no more problems, both pregnancy and birth went normally.

How was your mother coping with two babies and a husband who had such a demanding job?

With great difficulty. I remember my father’s job type was called turnus.* We would see him leave at any time of day or night, whenever he was called for, working as a train driver both on passenger and freight transports. Moreover, each year the railway timetable used to change, so everything was fluid in my father’s life, everything was moving. Pretty much the way it would be for me, much later.

At home, on the other hand, things had to be very well organized for him. My father had his briefcase and his tiny food containers, which Mom used to fill up. There was no other way, nobody would stop the train for him to eat. He had to carry his food with him, so that he could be always on the move.

While we were still in our infancy, my mother had to stay with us. Later, she tried once more to convince my father to let her take a job, but Dad still did not agree. He was educated in this silly belief that women should be kept at home . . . and Mom had to give in . . . at first because she had to, then to keep things nice and quiet at home. . . .

Wouldn’t it have been better for both of them to work? They could have brought more money to the family and she could have had an occupation, especially since she was so gifted at tailoring. . . .

My mom had us two in her care and money issues weren’t too many in my family because the four gardens provided for us, and my father had a large-enough salary. His job was very hard indeed, but also very well paid. I do not know how much money he made exactly, but I know they used to talk about it.

As we grew older, however, things began to get worse in the country, and shortages of all kinds appeared—especially of the simple things: food, clothing and footwear, everyday things.

Through the efforts of my parents, but also thanks to the generosity of those around us who had discovered us and helped us ever since we were very small, we did not feel the hardships for a very long time. We lived in a bubble, protected, isolated from what was happening in the country.

Perhaps this protective circle appeared around our family because of us. The fact that I was a child with a special talent determined all our relatives and teachers, and everyone I met really, to want to support me somehow. They would create a shield around us—me and Elena—even if disaster was lurking about.

The age difference was not great—how well did you get along?

From the moment Elena—Nina as we used to call her—was able to set her eyes on me and know who I was, we were always together.

We used to have a hard time convincing people that we were sisters, because we looked nothing like each other, but we were always treated and dressed like twins. Angela and Elena Burlacu. Gina and Nina. Whoever knew our family was able to understand where each of us had borrowed her features. Elena was blonde with green eyes, and had curly hair. Our father’s sister was blonde and curly like her, but Nina’s eyes and mouth were from our mother. Everyone was saying that she was more beautiful, that she was more . . . and that’s exactly how she was.

I was brunette with very straight hair. I took more from my father’s side and from Grandma Victoria, his mother. I remember that I always had my hair short and my fringe was caught in a hairpin, to prevent it from covering my eyes. Nina, with her curly hair, looked great irrespective of her haircut. I did not. I was not too good-looking when I was little, or at least this is how I saw myself. . . . Only later on I improved.

In terms of personalities, we could not have been more different. My sister was voluble, outspoken, whatever space you would give her she would take it all. She always wanted to be different from me and was much fiercer. At school she was very intelligent, a quick learner, she had good grades and was always best in her class. My grades, by comparison, were not quite at the same level. Still, that did not bother me—on the contrary, it suited me to let her take the limelight. For fear I would embarrass myself, I preferred to sit in my corner and say nothing, to go unnoticed as much as possible.

A very big difference compared to today’s Angela Gheorghiu . . .

Believe it or not, at the time, wherever you’d put me, there I stayed, and things remained this way until much later. I had no courage to speak up. If we knew each other and we would get close to each other, I would open up, I would speak, but otherwise not. Elena, on the other hand, was a whirlwind of joy. Whenever guests came to our house, usually colleagues of my father, I used to shut down or lock myself up physically, in another room. I dared not utter one word the whole time; I was afraid that I could embarrass myself, that I did not know enough things so that I could properly hold a conversation. I was extremely shy.

Rather than have the world misjudge me, I preferred to remain silent. I was very much aware of what I was doing and I was even wondering if I would ever get to talk the way I would have liked. I was suffering from huge stress as I was afraid I did not know enough, could not do enough, was not beautiful enough, was not learned enough. In short, I thought I was not enough. . . .

Also, in our household, obedience and respect for the school, for learning, was an obsession, almost like a disease. Any child had to achieve more than his or her parents. More than just . . . enough. In my turn, I had to be the cleanest, best groomed, best clothed, and, of course, I had to take the highest grades.

None of this was easy. We used to heat our home with wood stoves. Up until I was eighteen, we had no running water and no sewage system inside the house, but only a water pump in the yard. We used to bathe in bălii, some large water tanks. The water used to be warmed in some huge pots and poured in the tanks. Bath time was an entire ritual, for sure, just not in the sense we understand it today. It was much more work and much less relaxation. Mom always had to wash and starch everything, we had to be eternally spotless clean and have everything ironed to perfection. That, at some point, ceased to be fun for us—it demanded a lot of effort and patience on the part of children.

It was a great pressure to place on children. . . .

This obsession with being impeccable was not only my parents’. All people who sent their sons and daughters to school were in some sort of competition. And among themselves, the ch...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- 1. Poems of Childhood

- 2. Study, Study, Study

- 3. Communist Romania and the Path of Music

- 4. Romance and Revolution

- 5. Falling in Love with Covent Garden

- 6. A Star Is Born

- 7. New Beginnings

- 8. Dramas and Traumas

- 9. Royal Encounters

- 10. Becoming Tosca

- 11. Choices and Launches

- 12. Restoring My Faith in Love

- Timeline of Career Highlights

- Discography

- Index

- Illustrations