eBook - ePub

Defending the Master Race

Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Scholars have labeled Madison Grant everything from the "nation's most influential racist" to the "greatest conservationist that ever lived." His life illuminates early twentieth-century America as it was heading toward the American Century, and his legacy is still very much with us today, from the speeches of immigrant-bashing politicians to the international efforts to arrest climate change. This insightful biography shows how Grant worked side-by-side with figures such as Theodore Roosevelt to found the Bronx Zoo, preserve the California redwoods, and save the American bison from extinction. But Grant was also the leader of the eugenics movement in the United States. He popularized the infamous notions that the blond-haired, blue-eyed Nordics were the "master race" and that the state should eliminate members of inferior races who were of no value to the community. Grant's behind-the-scenes machinations convinced Congress to enact the immigration restriction legislation of the 1920s, and his influence led many states to ban interracial marriage and sterilize thousands of "unworthy" citizens. Although most of the relevant archival materials on Madison Grant have mysteriously disappeared over the decades, Jonathan Spiro has devoted many years to reconstructing the hitherto concealed events of Grant's life. His astonishing feat of detective work reveals how the founder of the Bronx Zoo wound up writing the book that Adolf Hitler declared was his "bible."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Defending the Master Race by Jonathan Spiro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

The Evolution Of Scientific Racism

American of Americans,

with Heaven knew how many Puritans and Patriots behind him.…

His world was dead.

Henry Adams

1 Big-Game Hunter

The vision of some of the most advanced thinkers is even yet obscured by the lingering cobwebs of the myths they absorbed in their youth.

Madison Grant

To Promote Manly Sport with the Rifle

In December of 1887, twenty-nine-year-old Theodore Roosevelt, back in his native Manhattan after a two-year stint playing cowboy in the Badlands, hosted a dinner party for ten of his closest chums. Among those in attendance were his dashing brother Elliott Roosevelt and the influential naturalist George Bird Grinnell (editor of the nation’s foremost periodical for sportsmen, Forest and Stream). They were all men of wealth and prominence, and we can rest assured that there were no “mollycoddles” in the group: all were experienced in, and devoted to, the “manly outdoor sports,” especially big-game hunting in the wilds of North America.1

After the plates were removed, the guests began spinning tales of their hunting exploits and frontier adventures. Teddy was enjoying it all immensely, and it occurred to him that it would be bully if the group could meet on a more regular and formal basis. He proposed that they form a club for big-game hunters who would gather to discuss matters of common interest and to share hunting lore. The club, according to Roosevelt, would be “emphatically an association of men who believe that the hardier and manlier the sport is, the more attractive it is, and who do not think that there is any place in the ranks of true sportsmen … for the man who wishes to … shirk rough hard work.”2

This proposal was applauded by his guests, one of whom wryly suggested that the club be named “The Swappers,” since they were obviously going to be spending the bulk of their time swapping stories, “true or otherwise,” of their escapades. Roosevelt was not amused, and convinced the group to call their new association “The Boone and Crockett Club” in honor of “those two typical pioneer hunters Daniel Boone and Davey Crockett, the men who have served in a certain sense as the tutelary deities of American hunting lore.”3

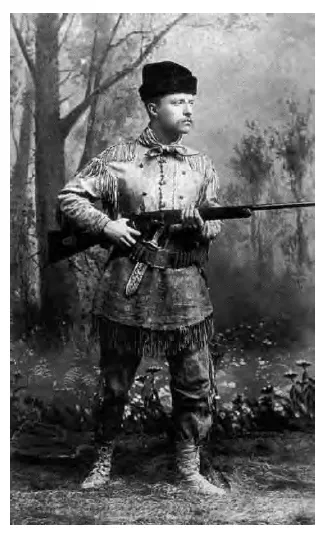

Teddy in the 1880s, looking manly in custom-made buckskin and Tiffany-carved knife.

Roosevelt and company drew up a constitution declaring that the chief object of the Boone and Crockett Club was “To promote manly sport with the rifle.” Membership was limited to an elite core of one hundred hunters who had killed large North American game animals of at least three different species (identified as bear, buffalo, caribou, cougar, deer, elk, moose, mountain sheep, musk ox, pronghorn antelope, white goat, and wolf). Though not explicitly stated in the original constitution, it was understood that said specimens must be full-grown adult males, as the killing of females or the young was considered beyond the pale. Furthermore, the trophies must have been killed “in fair chase,” which meant that such unsportsmanlike practices as “crusting” (killing game rendered helpless in deep snow), “jacking” (shining lanterns into the darkness to hypnotize passing animals), and “hounding” (driving prey into a lake with dogs) were verboten.

Well-bred hunters like Theodore Roosevelt and George Bird Grinnell were outraged by such uncouth practices, which were “unworthy of gentlemen or of sportsmen.” After all, anyone strong enough to pull a trigger could be a “hunter”; the true sportsman therefore had to find a way to set himself apart from the rude killers. This was accomplished via an aristocratic code of ethics that held that the hunter measured his success not by the quantity of game he killed but by the quality of the chase. The point was that a gentleman did not hunt for crass economic reasons; he hunted for sport—and an activity is not a sport unless there are challenges to be overcome and a clear set of rules about how to confront those challenges. Thus, for example, in addition to abjuring unsportsmanlike practices, the sport hunter willingly limited the technological sophistication of his weapon; he passed up the easy shot in favor of killing at the farthest possible range; he preferred the taking of a single fine specimen to the slaughter of a dozen inferior heads; and so forth. This was in direct contrast to the “market hunters,” those commercial hunters (members of one of the oldest trades in America) who supplied the urban markets with game. Driven by the profit motive, the despicable market hunters utilized the most effective weaponry, actively sought the easy kill, and had no qualms about shooting young or even female animals. “It is becoming a recognized fact,” huffed George Bird Grinnell’s Forest and Stream in 1889, “that a man who wastefully destroys big game … has nothing of the true sportsman about him.”4

The first official meeting of the Boone and Crockett Club took place in February 1888, and Theodore Roosevelt was elected president of the organization. Invitations to join the club were sent to a select number of candidates, and the membership roster eventually included some of the more influential citizens in the United States, such as Henry Cabot Lodge (the stalwart senator from Massachusetts), Gifford Pinchot (the conservationist), Albert Bierstadt (the landscape artist), T. S. Van Dyke (the most popular outdoor writer of his day), Clarence King (the Western explorer), Carl Schurz (the former secretary of the interior), Carl Akeley (the African explorer), Thomas B. Reed (the Speaker of the House), Lincoln Ellsworth (the explorer), Henry L. Stimson (secretary of war for both Taft and FDR, and secretary of state for Hoover), Henry Fairfield Osborn (America’s leading paleontologist), John Hays Hammond (the international mining engineer), Francis G. Newlands (the powerful senator from Nevada), George Eastman (the founder of Eastman Kodak), Elihu Root (TR’s secretary of state), Charles Curtis (the vice president of the United States), Owen Wister (the novelist whose best-selling The Virginian was dedicated to his Harvard classmate Theodore Roosevelt), and many others. They were all moneyed sportsmen “whose large wealth,” noted George Bird Grinnell, enabled them to “indulge to the fullest extent their fondness for hunting.” They were also the political and cultural leaders of the nation. Scions for the most part of venerable eastern families, and alumni of Ivy League schools, when they were not hunting together out west they were socializing together at the exclusive Century, Cosmos, Union, Metropolitan, and University Clubs of New York City and Washington, D.C. The members of the Boone and Crockett Club, explained Forest and Stream, were “men of social standing” whose opinion was “worth regarding” and whose influence was “widely felt in the best classes of society.” They were, in short, the patricians of the United States of America.5

The Yale Man

In 1893, a key event in the history of the Boone and Crockett Club—and of the conservation movement in America—took place when debonair twenty-eightyear-old lawyer Madison Grant, himself of patrician stock, was admitted into the club.

Grant was born on November 19, 1865, in his grandfather’s house in the posh Murray Hill area of Manhattan (three blocks south of the J. P. Morgan mansion and one block east of where the Empire State Building would be built). He was the heir of a rather distinguished American family. Madison Grant’s mother, Caroline Manice, was a descendant of Jesse De Forest, the Walloon Huguenot who in 1623 recruited the first band of colonists to settle in the New Netherlands. After securing a number of land grants on Manhattan Island, De Forest’s descendants prospered in the Dutch colony and played a prominent role in the social life of New Amsterdam (and then New York City).

On his father’s side, Madison Grant’s first American ancestor was Richard Treat, dean of Pitminster Church in England, who in 1630 was one of the first Puritan settlers of New England. Treat’s descendants included Robert Treat (a colonial governor of Connecticut and founder of the city of Newark, New Jersey), Robert Treat Paine (a signer of the Declaration of Independence), Charles Grant (Madison Grant’s grandfather, who served as an officer in the War of 1812), and Gabriel Grant (the father of Madison), a prominent physician and the health commissioner of Newark. When the Civil War broke out, Dr. Grant organized the Second New Jersey Volunteers and was eventually awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest military award for bravery that can be given to any citizen of the United States. The citation extolled in particular Grant’s personal daring at the battle of Fair Oaks, where he engaged in actions far “beyond the call of duty, thus furnishing an example of most distinguished gallantry.”6 It was at Fair Oaks that Grant used his medical skills to save the life of General O. O. Howard, who went on after the war to found Howard University and head the Freedmen’s Bureau. Dr. Grant and General Howard remained lifelong friends.

In sum, Madison Grant could proudly number among his ancestors Dutch grandees, Puritan divines, colonial magistrates, revolutionary patriots, and decorated soldiers. For centuries his antecedents had been accustomed to wealth, power, and deference, and in a country without a titled nobility they could lay as good a claim as any to being true American aristocrats.

Grant was the oldest brother among four siblings (DeForest was born in 1869, Kathrin in 1872, and Norman in 1877). The children’s summers, and many of their weekends, were spent at Oatlands, the beautiful Long Island country estate built by their grandfather DeForest Manice in the 1830s. The turreted mansion at Oatlands, with its molded ceilings, rich oak paneling, and enormous stone fireplaces, was deemed by Architecture magazine to be “the best in design” of all American mansions of the Strawberry Hill style.7 This impressive edifice was set amidst elaborate grounds and stables that, according to Architecture, had “the broad sweep and spacious dignity of the English park, together with the air of stability which belongs to the British country place.” As a child, Madison Grant loved to roam the estate, which was famous, among other things, for its elegant flower gardens and tropical conservatory. In addition, Madison’s grandfather had gone to great pains to plant all manner of unusual trees, including Chinese magnolias, Spanish chestnuts, a cedar of Lebanon brought from the Holy Land, and a European linden under which his guest the Comte de Paris (grandson of King Louis-Philippe and heir to the French throne) spent many summer afternoons during his post-1848 exile.8

Little wonder that Madison Grant was fascinated from an early age with natural history. As a result of his summertime forays through the Long Island countryside, the future founder of the Bronx Zoo amassed an extensive boyhood collection of rare reptiles and fishes, and he later confided to his friend Henry Fairfield Osborn that, from childhood, he had been interested in animals: “I began by collecting turtles as a boy and have never recovered from this predilection.” Years later, after Grant had grown up and moved away, the Man-ice Woods on the north side of Oatlands were cut down to make room for the Belmont Park Race Track, and the mansion was transformed into the clubhouse of the Turf and Field Club (on whose governing board sat Madison Grant).9

As a member of the eastern patriciate, Madison Grant was educated by private tutors, though he obtained most of his worldly knowledge on trips abroad with his father. On one such excursion, they journeyed to the ruins of ancient Troy where, if the testimony of his friend H. E. Anthony is to be believed, young Madison “sat on the crumbling walls and chanted Homer’s Iliad.”10

At the age of sixteen, Madison was sent to the German city of Dresden, where for the next four years European tutors provided him with the best possible classical education. During this time he managed to travel to every country in Europe (where he visited all the zoos and most of the natural history museums of the continent) and throughout North Africa and the Middle East as well. But his most significant visit was to Moritzburg, the baroque hunting lodge just outside Dresden, where my guess is that Grant found himself transfixed by the extensive collection of red deer antlers. The trophies—which had been collected three hundred years earlier—were impressively large, and the more the young student stared at them the more troubled he became. At some point, it occurred to him what was amiss: antlers of that size simply did not exist anymore on living European deer. Grant realized that, contrary to the Victorian understanding of evolutionary progress, the red deer had been getting smaller and smaller over the years. The species was actually degenerating.

Furthermore, Grant’s naturalistically inclined mind apparently put together what he knew of the geographic range of the red deer, along with the sizes of the various specimens he had encountered in the wild, and he instantly envisioned a perfect continuum: At the far eastern edge of the red deer’s range (in the Caucasus) the animal was almost as large as it had been in the sixteenth century. But toward the west (in the Carpathians) the deer began to diminish in size. Even farther west (in Saxony) the stags were smaller still, and at the far western limit of the animal’s range (in Scotland) the red deer had shrunk to their smallest proportions.

Grant reasoned that this decline in size was indubitably the result of trophy hunting. Trophy hunters, of course, target the largest bulls with the finest antlers, which leaves the breeding to the inferior males. As one moves from east to west across Europe, the human population increases, as does the number of hunters, and the inevitable result is an ever-greater decline across space, and over time, in the size and vigor of the deer stock. In other words, as human civilization advanced, the deer declined. And Grant was struck by the fact that if the trend were to continue, the red deer would diminish in size and vitality to the point where ultimately the species would not be able to survive in the wild.11

After four years of study and travel abroad, Grant returned to the United States in 1884, and as a matter of genetic imperative applied to enter Yale University. Candidates for admission to Yale in the 1880s were examined over a three-day period in four subjects: mathematics, German, Greek grammar, and Latin grammar. It is a sobering thought that probably not a single American teenager is alive today who could have qualified for admission to Yale in 1884. Madison Grant, on the other hand, passed with flying colors; in fact, he was admitted as a sophomore after demonstrating his mastery of the freshman curriculum (including Socrates, Herodotus, Euripides, Livy, Horace, and trigonometry).

With the exception of the courses of Professor William Graham Sumner (who engaged the students in heated discussions that invariably concluded with the professor assuring them that “as the rich grow richer, the poor grow richer also”), Grant’s classmates did not find their Yale studies to be stimulating. “Most of our classrooms were dull,” remembered William Lyon Phelps, “and the teaching purely mechanical; a curse hung over the Faculty, a blight on the art of teaching. Many professors … never showed any living interest, either in the studies or in the students.” Certainly, Madison Grant seems not to have been wholly engaged with his studies. Not surprisingly to anyone who has read The Passing of the Great Race, Grant consistently earned among the higher scores in composition but ranked near the bottom of his class in logic. Within a few years, Grant’s mind would possess a prodigious amount of knowledge about ethnology and natural history, but it would all be acquired by independent reading and experience subsequent to his graduation from Yale.12

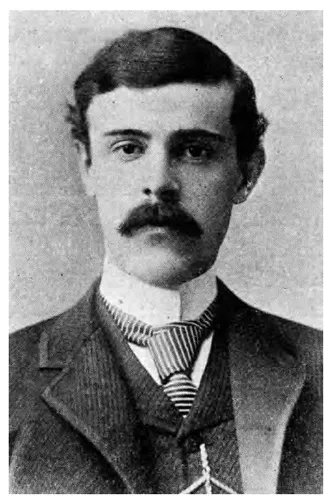

Madison Grant, class of 1887. His classmates confessed that their chief hobbies at Yale were loafing, smoking, dear hunting, swinging golf clubs, and “killing time and mosquitoes.”

But, of course, it was understood that the formative experiences at Yale took place not in the lecture halls but on the playing fields, at the eating clubs, and in the Greek-letter societies. And the end product of this New Haven–style social...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Madison Grant: The Consensus

- Introduction

- PART I. THE EVOLUTION OF SCIENTIFIC RACISM

- PART II. CONSERVING THE NORDICS

- PART III. EXTINCTION

- Epilogue. The Passing of the Great Patrician

- Appendix A: Organizations Served by Madison Grant in an Executive Capacity

- Appendix B: The Interlocking Directorate of Wildlife Conservation

- Appendix C: Selected Members of the Advisory Council of the ECUSA

- Appendix D: Selected Members of the Interlocking Directorate of Scientific Racism

- Key to Archival Collections

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index