- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

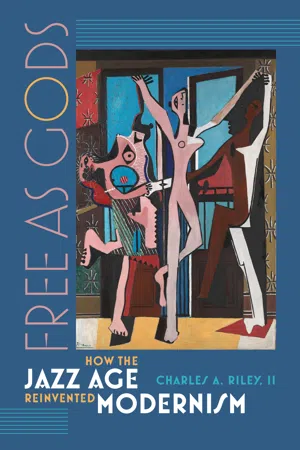

Among many art, music and literature lovers, particularly devotees of modernism, the expatriate community in France during the Jazz Age represents a remarkable convergence of genius in one place and period—one of the most glorious in history. Drawn by the presence of such avant-garde figures as Joyce and Picasso, artists and writers fled the Prohibition in the United States and revolution in Russia to head for the free-wheeling scene in Paris, where they made contact with rivals, collaborators, and a sophisticated audience of collectors and patrons. The outpouring of boundary-pushing novels, paintings, ballets, music, and design was so profuse that it belies the brevity of the era (1918–1929). Drawing on unpublished albums, drawings, paintings, and manuscripts, Charles A. Riley offers a fresh examination of both canonic and overlooked writers and artists and their works, by revealing them in conversation with one another. He illuminates social interconnections and artistic collaborations among the most famous—Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Gershwin, Diaghilev, and Picasso—and goes a step further, setting their work alongside that of African Americans such as Sidney Bechet, Archibald Motley Jr., and Langston Hughes, and women such as Gertrude Stein and Nancy Cunard. Riley's biographical and interpretive celebration of the many masterpieces of this remarkable group shows how the creative community of postwar Paris supported astounding experiments in content and form that still resonate today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Free as Gods by Charles A. Riley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

FREEDOM

ANYTHING GOES

“Live it up to write it down”1 was the systole and diastole of the Jazz Age, turning loose on the page, stage, or canvas the youthful excesses of a blissful circuit of parties without end in Montparnasse, on the Place Vendôme, or at the Côte d’Azur. The war was over, and the bubbles were endlessly rising in the champagne. At café tables dappled with spring sunshine, new arrivals fueled by espresso and Armagnac filled postcards with rapturous accounts of artistic breakthroughs that transgressed old boundaries of genres and taste. John Dos Passos marveled: “We were hardly out of uniform before we were hearing the music of Stravinsky, looking at the paintings of Picasso and Juan Gris, standing in line for opening nights of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Ulysses had just been printed by Shakespeare and Company. Performances like Noces and Sacre du Printemps or Cocteau’s Mariés de la Tour Eiffel were giving us a fresh notion of what might go on the stage.”2 Ernest Hemingway’s famous phrase was actually an aside to “a friend” that furnished the epigraph and title for his memoir: “If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.”3

The alarming thrill of “dancing on dynamite” was Nancy Cunard’s drug: “And Paris / Rolls up the monstrous carpet of its nights.”4 After his second day in town, Hart Crane filled a postcard from the Hôtel Jacob with a catalogue of excess: “Dinners, soirees, poets, erratic millionaires, painters, translations, lobsters, absinthe, music, promenades, oysters, sherry, aspirin, pictures, Sapphic heiresses, editors, books, sailors, And How!”5

Everybody was there, breaking and remaking the rules—having been licensed by the musicians to take improvisation as the gold standard of originality. Free to be gay, straight, black, Jewish, bohemian, or aristocratic, they slipped into fluid roles that defied specialization. The greatest painters of the age (Pablo Picasso and Fernand Léger) spent as much time backstage at the ballet as in their studios, while the hottest hands in jazz (Cole Porter and George Gershwin) and writing (Dos Passos and cummings) were clutching paintbrushes. Americans brought more than the Charleston to the transatlantic avant-garde party. Syncopated expressionism danced with neoclassical formalism. The giddy mix of rebellious riffs and serious modernism is found in major works by F. Scott Fitzgerald and T. S. Eliot, Gershwin’s tone poems and Igor Stravinsky’s concerti, Léger’s version of Charlie Chaplin’s bowler and George Balanchine’s Apollo. Eugene Jolas, the poet, journalist, and insider who connects so many of the figures in this book, recognized the essential “intercontinental” ingredient:

It is difficult today to project oneself from the tenebrous era of the universe concentrationnaire, with its accompanying esthétique of epigones, to that period of felicity and effervescence in the nineteen twenties and thirties, when writers of the Anglo American literary colony in Paris competed with their French contemporaries in imagining new mental landscapes, in an atmosphere of complete intellectual liberty. We seem now to have been living in a golden age of logos. Many of us had taken refuge from the bleakness of the Volstead regime in the more friendly climate of Montparnasse and Montmartre, and we were hell-bent on discovering new continents of the mind as well. Daring experimentation with words, colors and sounds was the chief pre-occupation of an intercontinental avant-garde that extended across continents and did not pause until that day in 1929 when Wall Street “laid its historic egg.”6

Jazz Age Paris had room enough for artists who chose an aesthetic of extreme order as well as those who needed to be, as Sergei Diaghilev decreed, “free as gods.”7 It had a special place for a wilder bunch who pushed liberty to its limits, abandoning their art to ecstasies that, when they were fortunate, exceeded anything they had ever accomplished back home. Malcolm Cowley claimed that Fitzgerald wrote The Great Gatsby well above his ability: “To satisfy his conscience he kept trying to write, not merely as well as he could, like an honest literary craftsman, but somehow better than he was able. There was more than one occasion when he actually surpassed himself—that is, when he so immersed himself in a subject that it carried him beyond his usual or natural capacities as demonstrated in the past.”8 These are the lost generation lessons in incandescent dissipation, the cautionary tales of “the beautiful and damned” (to cite the title of another work by Fitzgerald) whose talents burned out young. Dos Passos and cummings were so transported by their erotic and political passions that they flipped between fauve-style painting and exuberantly experimental writing, an alternating current of creativity with too many amps for one circuit. Gershwin offered glimpses of the potential of symphonic jazz with a rhapsody that he brazenly premiered in an unfinished state, but he died on a Los Angeles operating table at the age of thirty-eight, long before its possibilities could be realized. Crane finished his masterpiece The Bridge during Dionysian weekends at Crosby’s château. Before it was published, Crosby shot himself and a girlfriend in a murder-suicide pact. And a few months later, Crane leaped from the stern of the ship returning him to New York and the responsibility of running the family candy company. The Jazz Age formula for projecting joie de vivre into art was not without its shadows.

It is called the Jazz Age for a reason. A working knowledge of the music that propelled the literature and art is vital to any cultural history of the period. The advent of ragtime, blues, and New Orleans–style jazz changed the basic elements of composition on both sides of the pond and both sides of the aisle dividing serious from popular. The scale is not the same, the rhythms are famously skewed from the comfortable quadruple and triple beats underlying classical sonatas or dance forms, and the physical fabric of the sounds is novel. Instruments invented for jazz bands were unlike the standard-issue strings, winds, brass, and especially percussion that had served composers and players perfectly well for six hundred years. The epitome of this innovation furnishes a favorite George Gershwin anecdote about the source of the street scene noises in An American in Paris. Gershwin shopped in the auto parts stores of the Grande Armée neighborhood for taxi horns, squeezing the bulbs until he found just the right off-key honks and squawks. Although Gershwin’s original horns have been lost by his heirs, a new critical edition of the piece suggests that the familiar tones (A, B, C, and D natural as they have been played for seventy years) may have been incorrectly inferred from a manuscript annotation, tidying the urban noise into a more conventional musical phrase. Expect to be surprised by the rougher sound of an A-flat, B-flat, a higher D, and a lower A when you hear the revised version. The ultimate note of authenticity especially in their untuned iteration, the blaring bruit of the hectic traffic circle at the Arc de Triomphe, was collaged into the tone poem, a mimetic coup as startling as the trompe l’oeil cigar box top in Gerald Murphy’s Cocktail, Fernand Léger’s blown-up illustration of a siphon lifted from a Campari newspaper advertisement, or the slogans for Ford and Edison captured by Hart Crane from billboards along the route of the Twentieth Century Limited as it sped out of New York’s Grand Central Station into the US heartland.

In the musical history of the twenties, the taxi horns take their place beside the three whirling airplane propellers demanded in Darius Milhaud’s score for Création du Monde (just big fans, which annoyed the hell out of the audience when turned toward the listeners) as well as the typewriters and blanks from a starter’s pistol in Erik Satie’s ballet Parade, the electric bells and sirens in the Ballet Mécanique by George Antheil (for which Léger made a film), and the Ford car horns in Frederick Converse’s 1927 “Flivver Ten Million.” From honky-tonk pianos slammed by forearms to the piercing soprano sax of Sidney Bechet and the mellow C melody sax of his band mate Frank Trumbauer onward to Dizzy Gillespie’s bent trumpet and the electric guitar (invented by a Los Angeles jazzman in 1931), the physical culture of music was altered for and by jazz. The major aria in the most popular jazz opera (“I Got Plenty of Nuttin’” in Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess) is accompanied by a banjo. Not even the human voice was immune to alteration, if you consider the shouting of the players in big bands such as Fletcher Henderson’s and scat (supposedly invented by Louis Armstrong when the pages of his sheet music dropped to the floor during a recording session).

This sonic transformation can be experienced in a familiar way—under the fingers. Even a rank amateur can grasp the seismic shift in music making by taking a seat at the piano, applying the right thumb to middle C, and starting to play the jazz scale. The first two notes are the same as the classical C major scale (C and D natural, both white keys), but by the third note in the jazz scale (an E-flat), the door is opened to another world of intervals, harmonies, modulations, and melodies. It all changes with the flatted third and seventh: the E and B of the major scale are diminished, slipping that telltale half-step down to the black keys known as blue notes.

Jazz on the page or in the studio and hot jazz in flux were the two poles of the music in practice. The former was an engine of business. The first major blues composer was W. C. Handy, a collector, adapter, and arranger of the postbellum folk spirituals of freedmen. His influential “Memphis Blues” (1912) and “St. Louis Blues” (1914) were best-selling sheet music scores, and they were recorded by singers including Ethel Waters, Sophie Tucker, Gilda Gray, and Ted Lewis. The first version of the Victrola was in thousands of homes by 1916, and three years later major radio stations in Detroit, Michigan (WWJ); Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, (KDKA); and Newark, New Jersey, (WJZ) were operating. In 1926 NBC broadcast jazz programming, followed a year later by CBS. Powerhouse labels such as RCA Victor, Okeh, and Columbia were a force in the shaping of composition itself, since the timing and scoring of a piece (to ensure that the levels were balanced) were determined by the technology of the studio, the capacity of the long-playing disk, and the protocols of radio. While ragtime and the blues, its successor, originated in black culture, and the greatest singers and players were Joe “King” Oliver, Armstrong, Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Florence Mills, by 1920 the trade was in the developmental hands of Tin Pan Alley and Broadway. Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, George and Ira Gershwin, Hoagy Carmichael, Bing Crosby, and even Noël Coward (in “Russian Blues,” 1923) took up the standard thirty-two bar form, incorporating flatted thirds and fifths in the service of melody. George Gershwin’s mega-hit “Swanee” made its debut in 1919. By the beginning of the twenties jazz bands had rapidly outgrown the limited seating capacity of clubs in New Orleans and Harlem and were filling the major theaters of midtown New York and Chicago, where revues and musicals played to audiences of more than three thousand at a single performance. The all-black review Shuffle Along opened on May 23, 1921, on West 63rd Street in New York in what used to be a lecture hall. Its run lasted 504 performances, thanks to star turns by Josephine Baker and Mills and hits such as “I’m Just Wild about Harry.” Four years later, the show packed the huge Music Hall on the Champs-Élysées. In 1921, just a few blocks downtown from Shuffle Along, the Shubert brothers (Sam, Lee, and Jacob) opened the Jolson Theatre for their star Al Jolson and Fanny Brice, who introduced “My Man” in the Ziegfeld Follies. The song was translated from Mistinguett’s showstopper, “Mon Homme,” which she sang in New York for Florenz Ziegfeld’s revue Paris Qui Jazz (1920), an early example of the two-way traffic between Manhattan and Paris.

Even if its defining characteristic in performance is improvisation, with box office money on the line, jazz composers could not afford to just wing it. Musicians and dancers in big bands or the vast choruses of the Follies need order as much as freedom. The composers left maps to their meanings in scores and analyses by John Hammond, Antheil, Ernest Ansermet, Paul Whiteman, Carl van Vechten, and others. The ideal hot jazz morphed so quickly that rival players would jot down riffs on their cuffs during late-night jam sessions to try out the next day. One of the cribbers was Maurice Ravel, brought by a flutist from the Chicago Symphony late one night to the Nest, a club at the famous corner of Calumet and Thirty-Fifth on the city’s South Side, where jam sessions attracted competing virtuosi such as Oliver, Armstrong, Benny Goodman and Earl “Fatha” Hines. Amazed by the clarinet choruses of Jimmie Noone, he tried in vain to write down the runs. “Impossible!” Ravel said under his breath, before giving up to just listen.9

Steeped in imported jazz, exotic regional sounds, and avant-garde experimental music, the musical history of Paris from 1913 through 1929 was as vibrant as that of Vienna and Berlin, which belonged to Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern, the dour trio who stole more than their share of the modernist story. Ravel, Igor Stravinsky, and Milhaud traveled to New Orleans, Chicago, and Harlem to hear for themselves, puzzled and inspired by the liberating syncopation as well as the first major alteration of the scale since the introduction of equal temperament halfway through the 1700s. The watershed date for the jazz invasion of France is pinpointed as New Year’s Day 1918, when the two thousand infantrymen of the all-black (except officers) Fifteenth New York Regiment of the US National Guard (nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters in honor of the action they had seen at the Marne and the Argonne) marched down the gangplank at Brest behind their famous band under the direction of Lieutenant James Reese Europe, the popular society dance bandleader who had introduced the fox-trot. They swung the “Marseillaise” in march time, and the soldiers danced their way along the streets. It took eight or ten bars for the onlookers to figure out the melody, but when they did they saluted and promptly went wild. The band played the Nantes opera house on Lincoln’s birthday and then gave a massive outdoor concert before a crowd of 50,000, together with the Grenadier Guards, the Garde Républicaine, and the Royal Italian Band. The European band members were so baffled by the Hellfighters’ sound that they asked to examine the instruments.

Jazz quickly invaded the rest of Europe. The Old Dixieland Jazz Band and Southern Syncopated Orchestra were the toast of London in June 1919, sharing a five-month run at the Royal Philharmonic Hall. Mabel Mercer, Hines, Duke Ellington, Mills, and Ada “Bricktop” Smith committed themselves to extended tours that often led to years of expatriate life. One of the first ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part 1. Freedom: Anything Goes

- Part 2. Order: Blessed Rage

- Part 3. Truth: The Truest Sentence

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Color illustrations