eBook - ePub

Whistle Stop

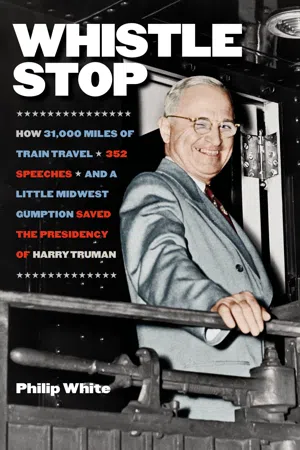

How 31,000 Miles of Train Travel, 352 Speeches, and a Little Midwest Gumption Saved the Presidency of Harry Truman

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Whistle Stop

How 31,000 Miles of Train Travel, 352 Speeches, and a Little Midwest Gumption Saved the Presidency of Harry Truman

About this book

President Harry Truman was a disappointment to the Democrats, and a godsend to the Republicans. Every attempt to paint Truman with the grace, charm, and grandeur of Franklin Delano Roosevelt had been a dismal failure: Truman's virtues were simpler, plainer, more direct. The challenges he faced—stirrings of civil rights and southern resentment at home, and communist aggression and brinkmanship abroad—could not have been more critical. By the summer of 1948 the prospects of a second term for Truman looked bleak. Newspapers and popular opinion nationwide had all but anointed as president Thomas Dewey, the Republican New York Governor. Truman could not even be certain of his own party's nomination: the Democrats, still in mourning for FDR, were deeply riven, with Henry Wallace and Strom Thurmond leading breakaway Progressive and Dixiecrat factions. Finally, with ingenuity born of desperation, Truman's aides hit upon a plan: get the president in front of as many regular voters as possible, preferably in intimate settings, all across the country. To the surprise of everyone but Harry Truman, it worked. Whistle Stop is the first book of its kind: a micro-history of the summer and fall of 1948 when Truman took to the rails, crisscrossing the country from June right up to Election Day in November. The tour and the campaign culminated with the iconic image of a grinning, victorious Truman holding aloft the famous Chicago Tribune headline: "Dewey Defeats Truman."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Whistle Stop by Philip White in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

| 1 | June |

My Dear Mr. President,

Never in my fifty one years of life have I had the temerity to write a letter to the President. However, when I tell you that I have known you personally while I served on the Ways and Means Committee of the Grand Lodge A.F. and A.M., that we have a close mutual friend in George Marquis of Independence, that we have many other mutual friends and acquaintances, then possibly you will not feel that I am being too presumptuous in offering you in all kindness a “grass roots” political suggestion.

Our Democratic Party has a hard row to hoe. We are beset on one side by reaction and on the other by a Communist dominated Progressive Party. Wallace cannot win. But his party is attracting many liberals who fail to see the dangers of Communist domination. Present trends indicate the victory of reaction at the polls this Fall. Normally the failure of a party or a candidate is not too catastrophic. But these are perilous times in the world.

I have always looked upon our Democratic Party as the truest vehicle of real progressive liberalism in the country. I still think that is true. But in order to win, its leadership is going to have to be able to electrify the electorate. Regardless of the justice or injustice I believe both popular opinion and opinions of liberals everywhere is that new leadership of the party is essential to victory this year.

Certainly none of your liberal leadership needs to be repudiated in any way. The Democratic party must continue your civil rights fight, anti inflation fight etc. You no doubt could have very great influence in the selection of a party leader for this campaign. Naturally in voluntarily stepping out of the place of leadership you would sacrifice personal prestige and political power. Yet you will recall that the Savior of mankind when upon a mountain top was confronted with this identical problem. His road to glory was the road of personal sacrifice. That has continued to be the road to glory throughout the ages.

Assuring you of my kindest personal regards, I am,

Sincerely,

H. H. Brummall1

He could take it from the Republicans. He could take it from the Dixiecrats and Progressives. Heck, Harry Truman could even take it from dissenting voices inside his own cabinet. But rudeness from one of his own, a guy from Missouri he knew, and a sanctimonious one at that? No. Particularly not when Brummall was asking him to invalidate all he had worked for by “voluntarily stepping out of the place of leadership.” The gall of this man!

His normally sunny disposition, conveyed with a smile that broke easily across his broad yet boyishly handsome face enhanced by mischievous hazel eyes, darkened like the sky of his native Missouri when a twister is coming. Most presidential replies are merely a boilerplate with a signature stamp or at best a hastily scrawled John Hancock at the bottom. But not this time. Truman picked up his pen and angrily scribbled a personal, and less than cordial, repost to Dr. Brummall of Salisbury, Missouri:

Dear Dr. Brummall,

I read your letter of the fifteenth with a lot of interest and for your information I was not brought up to run from a fight.

A great many of you Democrats in 1940 ran off after a certain Governor [Missouri’s former Governor Lloyd C. Stark], who was trying to cut my throat and he didn’t do it successfully—they are not going to succeed this time either.

I am certainly sorry that you feel the way you do. It is not a good way for a Missourian to feel at this time.

Sincerely yours,

Harry S. Truman2

Once his rage cooled, Truman decided he could use Brummall’s note to his political advantage. He wanted to fire a warning shot about his attitude to the election campaign to his detractors across the country, so he called in the tall, wiry Charlie Ross, his eloquent former boyhood friend, Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist, and now press secretary (as one of the inner circle the Republicans disparagingly called “The Missouri Gang”). Truman knew he could count on Ross—whose small, deep-set eyes focused intently on his subject when they spoke and who addressed Truman with the confidence that only comes from a decades-old association—for a frank opinion. Ross’s cautious and reserved manner often served to send the unpolished products of Truman’s enthusiastic and quick decision making back to the drafting table, and the president welcomed his old pal’s candor.3 The two discussed the matter for a couple of minutes and decided on a plan of action: Ross would share the sentiments of Brummall’s note and Truman’s reply with the press in mid-June 1948.

If it was coverage the president wanted, he most certainly got it. Time ran a piece on the exchange the following week, and the New Yorker compared Truman’s unusually frank response to the impersonal, template-based one he had sent to an attorney who had joined Brummall in calling for him to bow out of the Democratic race but which had not drawn the same ire: “The President has asked me to thank you for your letter of April 23. He has read it with interest, and wants you to know that he is always glad to receive suggestions such as yours.”4 Since the Brummall incident, counsel to the president Clark Clifford, the forty-one-year-old former naval officer who had quickly risen through the ranks to become one of Truman’s key advisers, had been mulling how best to put the president’s determination in the face of criticism to use in the 1948 election campaign. Clifford, whose height, dash, and sophisticated speaking manner contrasted sharply with his boss and made the society pages of Washington newspapers write “gooily” about him, according to veteran reporter A. Merriman Smith, was not just a favorite of the media.5 He was also a master planner, had a quick turn of phrase, and was trusted by Truman to oversee strategy for the coming political dogfight.

Clifford, Oscar L. Chapman (undersecretary of the interior), and several other members of Truman’s inner circle met every Monday in the Wardman Park Hotel apartment of Oscar R. Ewing, who had been vice chairman of the Democratic National Committee from 1942 to 1947 and was now an unofficial adviser to the president. Clifford called the group, which aimed to advance liberal policy in the White House and reveled in the secrecy of its gatherings, the “Monday Night Group,” and as they ate their usual weekly steak and downed several rounds, they talked shop.6 At one of these bull sessions in early spring 1948, Clifford asked Chapman to find an excuse for Truman to take a train trip out West in the coming weeks, a trial run for more sustained railroad campaigning in the fall. He had come up with this idea from the November 1947 memo penned by Washington attorney James Rowe, a confidant of FDR, for budget bureau director James Webb. The lengthy and detailed missive, which soon made it to Clifford’s desk and would direct many elements of the Truman team’s campaign strategy, included an exhortation that Truman should focus on “Winning the West.” Rowe went on to state that “political and program planning demands concentration upon the West and its problems, including reclamation, floods, and agriculture. It is the Number One Priority for the 1948 campaign.” Rowe then warned that the GOP had a foothold in many key western states. Thus, Clifford thought the president should start his battle for electoral seats in the West with a tour that would enable him to address millions of voters during the spring of 1948, long before the full fall campaign began.7

If Truman’s staff could pull this ambitious westward journey off, he would not be the first president to take to the rails to drum up support. Woodrow Wilson had tried it in 1919 to press his case for American leadership of the League of Nations, and Andrew Johnson had “swung around the circle” from Washington to Chicago in an attempt to get popular backing for his reconstruction blueprint. Clifford, however, hoped his chief would be more successful than Johnson or Wilson: the former failed in his mission and the latter’s arduous time on the tracks arguably hastened his death.8

After hearing Clifford out, Chapman got on the telephone to Robert Sproul, his friend who was in his eighteenth year as president of the University of California Berkeley, and who he knew was searching for a commencement speaker for the school’s June 1948 event.9 Sproul was a Republican and no fan of Truman, but he couldn’t pass up the PR opportunity. Truman’s advisers now had their excuse. The trip Clifford dubbed “The Shakedown Cruise” was on.10

In Clifford’s mind, such a tour was a necessity for several reasons beyond the thinking of James Rowe’s memo. First, Truman had hit rock bottom in the Gallup and Roper polls. By 1946 and 1947 the glow of wartime unity had melted away and postwar problems came to the fore, including union unrest—which led to millions of work days lost to strikes—agricultural tariffs, and a shortage of available and affordable housing. As these intensified, the nation no longer seemed to support its president. As a biographer of Truman’s rival, Republican Senator Robert A. Taft, put it: “To many Americans, Truman seemed inept, uncertain, vulnerable at the polls, a sad successor to Roosevelt.”11

Truman’s numbers rallied with the boldness of the “Truman Doctrine,” his ambitious plan for containing Soviet expansionism that he announced on March 12, 1947. But now, in spring 1948, with the president hobbled by his continual losses to the Republican majority in Congress, his controversial decision to recognize the nascent state of Israel, and with multiple candidates and possible candidates from both parties stealing the headlines—not least the now-iconic General Eisenhower—Truman’s brief surge was well and truly over.12

One April 1948 poll revealed that his approval rating had plummeted to a dire 36 percent, down 19 points from the September 1947 high-water mark. Another April statistical barometer had Truman losing the election by seven percentage points to Republican preconvention favorite Thomas E. Dewey, the popular, short, and debonair governor of New York, who had won his second term two years prior by a record margin. A month later, polling data suggested the Missourian would fall even harder against the capable, studious, and ambitious former governor of Minnesota and current University of Pennsylvania president Harold Stassen—a predicted loss by twenty-three points.13 Polling was by no means an exact science, but Gallup and its competitors had been honing their methods for a dozen years and Clifford and his fellow West Wing staff could see that Truman was in big trouble if the political winds didn’t shift before November.

Furthermore, Truman was stymied at every turn by the hostile Republican-controlled Congress, the sole aim of which seemed to be to stop Truman from getting any meaningful domestic legislation through. With widespread alarm at the USSR’s increasing aggression in Eastern Europe and Asia and the cooperative and bipartisan leadership of Republican Arthur Vandenberg in the Senate (a longtime supporter of Truman’s tough policies toward the Soviet Union) and Vandenberg’s counterparts in Congress, Truman found it easier to push through foreign policy legislation. In early spring 1948, Congress passed a bill to grant more than $5 billion in aid to Western Europe, and Truman signed the European Cooperation Act on April 3. This was the major legislation of what became known as the Marshall Plan.14 With this, he and his secretary of state George C. Marshall, the quick-minded, detail-oriented, take-charge US Army chief of staff who masterminded American victories in Europe and the Pacific in World War II, hoped to bolster Western Europe and parts of Asia against expansionist communism.

The funding approved by Congress would also bolster Turkish and Greek government forces as they continued to oppose communist takeovers. If the communists succeeded in capturing these countries, Marshall and Truman believed, it would not only embolden what Churchill called Soviet Russia’s “expansive and proselytizing tendencies,” but it could also start a domino effect of more democratic European nations toppling under the weight of communism’s westward march.15 And if China succumbed to the Maoist revolution and the power void in Japan was filled by Stalin’s puppets, another continent would be beholden to Moscow. By working across the aisle and reaching consensus on just about the only thing most Republicans and Democrats could agree on in 1948, Truman hoped such catastrophes would never come to pass. As Marshall put it when explaining the plan that would come to bear his name: “Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist.”16

Despite continued bipartisan support for the Marshall Plan and that it marked a personal triumph for his administration, Truman was still taking a beating in the press. The criticism was particularly sharp from conservative outlets such as the Chicago Tribune and southern papers that resented the far-reaching civil rights proposal Truman had sent to Congress and the Senate in February 1948. This included desegregating the armed forces, guaranteeing fair employment practices at the federal level, and introducing strict new antilynching laws.17

The outraged reaction from Democrats below the Mason-Dixon Line was swift in coming. “50 Southern Congressman Declare War on Truman’s Civil Rights Plan” screamed a front-page headline in the February 28 edition of the Kentucky New Era, typifying southern segregationist ire.18 Since June 28, 1947, when Truman became the first chief executive to speak to the NAACP and told of his intention to put to rest the inequity of Jim Crow, many Democrats in southern states had either castigated or deserted their leader, or both.19

Mississippi senator James Eastland, dubbed “The Voice of the White South,” encapsulated his region’s prevailing attitude toward Truman’s plans when he lamented, “The South as we know it...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction: The Election of 1948

- 1. June

- 2. July

- 3. August

- 4. September

- 5. October

- 6. November 2, 1948

- 7. The World According to Harry Truman

- Afterword: The Legacy of Truman’s Triumph and Dewey’s Defeat

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index

- Photographs