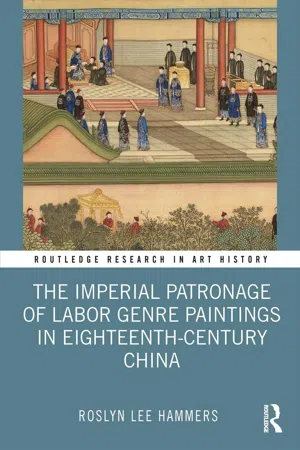

The Imperial Patronage of Labor Genre Paintings in Eighteenth-Century China

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Imperial Patronage of Labor Genre Paintings in Eighteenth-Century China

About this book

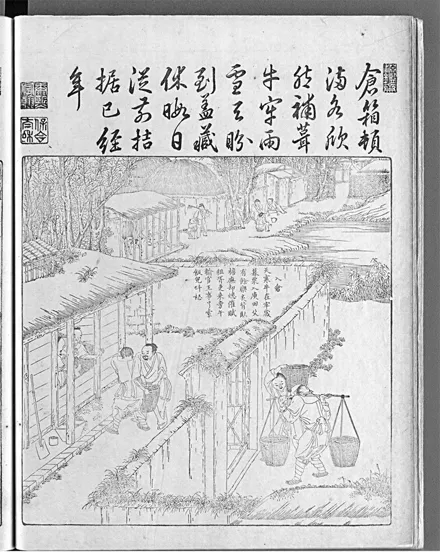

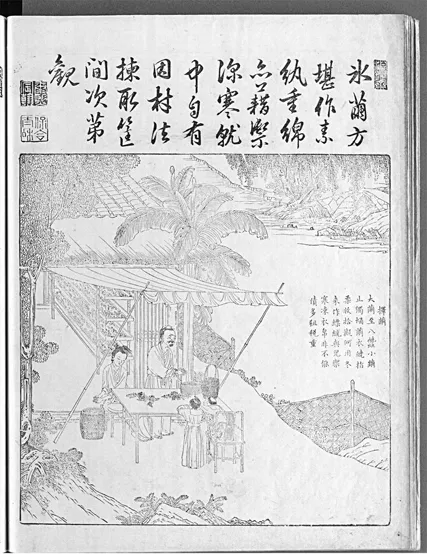

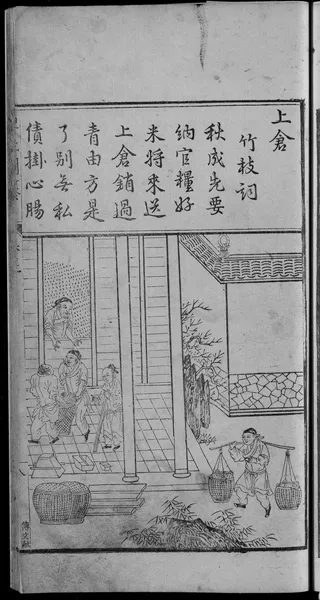

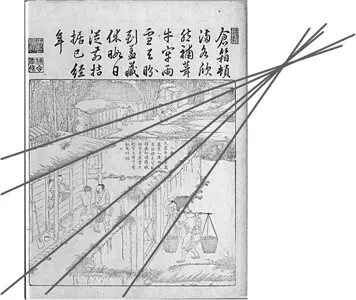

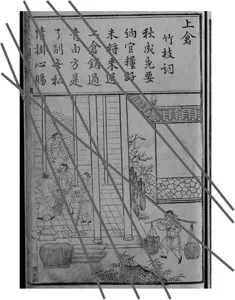

This book examines the agrarian labor genre paintings based on the Pictures of Tilling and Weaving that were commissioned by successive Chinese emperors.

Furthermore, this book analyzes the genre's imagery as well as the poems in their historical context and explains how the paintings contributed to distinctively cosmopolitan Qing imagery that also drew upon European visual styles. Roslyn Lee Hammers contends that technologically-informed imagery was not merely didactic imagery to teach viewers how to grow rice or produce silk. The Qing emperors invested in paintings of labor to substantiate the permanence of the dynasty and to promote the well-being of the people under Manchu governance. The book includes English translations of the poems of the Pictures of Tilling and Weaving as well as other documents that have not been brought together in translation.

The book will be of interest to scholars working in art history, Chinese history, Chinese studies, history of science and technology, book history, labor history, and Qing history.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1 The Kangxi Emperor Reworks the Pictures of Tilling and Weaving

The Iconography of the Kangxi Version and a Ming-Era Farmers’ Almanac

Western Perspective in the Imperially Commissioned Pictures of Tilling and Weaving

Chinese Agrarian Heritage Recovered and Revised

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Ennobling Agrarian Work of the Qing Emperors

- 1 The Kangxi Emperor Reworks the Pictures of Tilling and Weaving

- 2 The Noble Labors of the Yongzheng Emperor

- 3 The Preoccupations of the Qianlong Emperor

- 4 The Sagacious Vocation of the Qianlong Emperor

- Epilogue: Working Toward Closure, the Jiaqing Emperor Reforming Imperial Labor

- Appendix A: Imperially Commissioned Poems to the Pictures of Tilling and Weaving

- Appendix B: Primary Documents Related to the Pictures of Tilling and Weaving and Agrarian Labor

- Selected Bibliography

- Index