- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Microalgae in Waste Water Remediation

About this book

Microalgae in Waste Water Remediation aims to point out trends and current topics concerning the use of microalgae in wastewater treatment and to identify potential paths for future research regarding microalgaebased bioremediation. To achieve this goal, the book also assessing and analyzes the topics that attract attention among the scientific community and their evolution through time. This book will be useful to the students, scientists and policy makers concerned with the microalgae mediated management of wastewater effluents and its applications in overall future sustainable development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Microalgae in Waste Water Remediation by Arun Kumar,Jay Shankar Singh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technik & Maschinenbau & Biologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Microalgae I: Origin, Distribution and Morphology

Introduction

Microalgae are considered as a large group of microscopic, phototrophic organisms that include cyanobacteria, prochlorophytes and eukaryotic algae. They are found in diverse ranges of terrestrial, freshwater and marine habitats; and also exist in extreme environments, such as snow, sea ice, deserts, hot springs and salt lakes (Rothschild and Mancinelli 2001, Vincent 2010, Singh 2014, Hopes and Mock 2015, Singh et al. 2016). They are ubiquitous in distribution, survive in most habitats that have moisture and sufficient light conditions, and are quite common in freshwater lakes and oceans as part of the phytoplankton community.

Organisms like cyanobacteria originated about 2.7-2.6 billion years ago in the Archean eon of the Precambrian era; which later may have been responsible for a radical transformation involving global oxygenation in the atmosphere of the Earth (Canfield 2000, Holland 2006, Kulasooriya 2011). The primary endosymbiotic event between cyanobacteria and the unicellular heterotrophic eukaryotic host gave rise to chlorophytes, glaucophytes and rhodophytes containing membrane-bound organelles known as plastids (Falkowski et al. 2004, Miyagishima 2011). Later a secondary endosymbiotic event involving green and red algae with new heterotrophic eukaryotes gave rise to euglenoids and chlorarachniophyte, cryptophytes, dinoflagellates and chromophytes (diatoms) having green or red plastids with additional membranes (Cavalier-Smith 1999).

In oceans, cyanobacteria and eukaryotic microalgae are together responsible for just over 45% of global primary production (Field et al. 1998), which play a large role in nutrient cycling by providing nutrition to other organisms and later on death, sinking their biomass (organic matter) to the interior of oceans. The regular sinking of algal biomass also enriches the ocean’s interior with fixed atmospheric CO2, resulting in maintaining global CO2 levels. This phenomenon is more closely observed during seasonal excess microalgal growth (often a single or a few species of microalgae) or simply algal blooms, occurring due to excess availability of nutrients such as nitrate and iron (Boyd et al. 2000). On depletion of nutrients, the microalgal community begins to sink, which are responsible for cycling organic and inorganic products. Some microalgal groups i.e., diatoms and coccolithophores have geological contributions such as diatomite and chalk deposits, through sinking of their intricate shells of silica and calcium carbonate. It was also indicated that sinking and depositions of microalgal lipids was linked to marine oil reserves.

Origin and Evolution

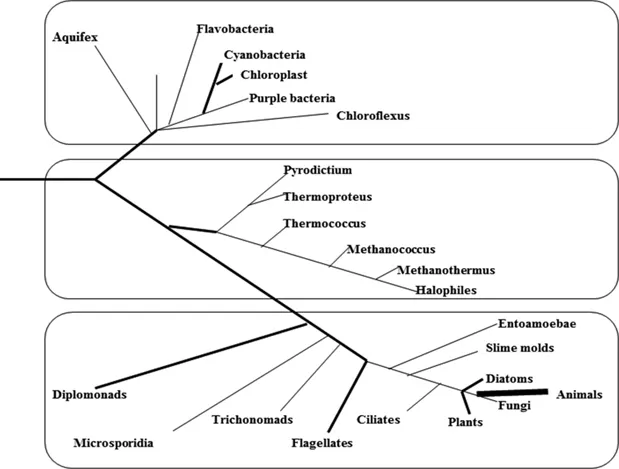

The phylogeny of microalgae and related organisms are understood or interpreted through ultrastructural and molecular evidence of conserved features like plastid and mitochondrial structures, flagellar hairs and roots, plastid mitotic apparatus and ribosomal RNA gene sequencing (Fig. 1.1). There are several problems such as the dynamic nature of research and discussions related to the phylogeny of eukaryotes, current doubts about the placement of a number of groups, requiring further research in ecology and distribution, biochemical diversity and applied phycology; which limits the scope of a classification scheme based on a traditional approach. The traditional approach, primarily considers features like pigmentation, thylakoid organization and other ultrastructural features of the chloroplast, the chemical nature of the photosynthetic storage product, structure and chemistry of the cell wall, and the presence of flagella (if any) and their number, arrangement and ultrastructure; to classify the algae into major groups in to ‘divisions’ (which are equivalent to zoological ‘phylum’).

Figure 1.1: Three domain kingdom classification systems (Woese et al. 1972).

Based on fossil records, it was established that the first cyanobacteria originated about 2.7–2.6 billion years ago in the Archean era of Precambrian period that created small oxygen ‘oases’ within the anoxygenic environment (Andersen 1996, Buick 2008, Blank and Sanches-Baracaldo 2010, Shestakova and Karbysheva 2017). Due to these small oxygen oases, global oxygenation of the atmosphere occurred between 2.45 and 2.23 billion years ago, often known as the Great Oxidation Event (GOE). Sergeev et al. (2002) and Zavarzin (2010) suggested that cyanobacteria gradually replaced methane from the anoxygenic environment, leading to the transformation of global geochemical conditions that significantly affected the development of interdependent biogeochemical cycles i.e., carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and sulfur. Due to the alternation in methane concentration and some lithospheric processes, it induced the cooling of the Earth’s surface and later glaciation activities in the early Proterozoic period. These alternative changes in climatic conditions, further paved the way for the evolution and diversification of cyanobacteria (Garcia-Pichel 1998, Sorokhtin 2005, Kopp et al. 2005).

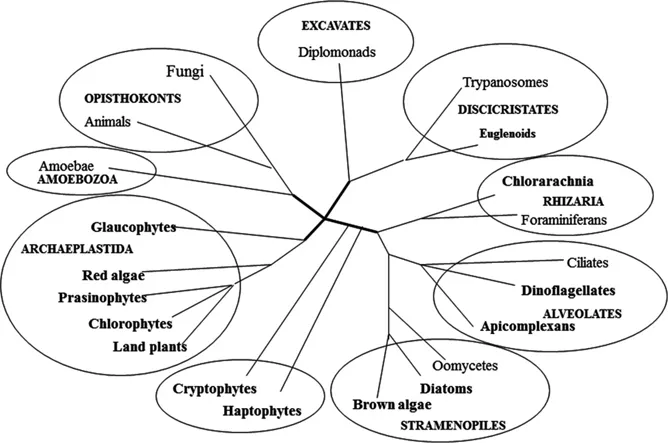

In recent times, the eukaryotic domain is categorized in to six major super-groups: Archaeplastida, Chromalveolata, Excavata, Rhizaria, Amoebozoa and Opisthokonta (fungi and animals) (Fig. 1.2) (Adl et al. 2005, Keeling et al. 2005, Reyes-Prieto et al. 2007, Gould et al. 2008, Archibald 2009), of which the first four super-groups mostly includes the photosynthetic members. The chloroplasts originated more than 1 billion years ago, through an endosymbiotic incident between a free-living cyanobacterium and an endosymbiont in a eukaryotic host cell. It is also indicated that all chloroplasts and their non-photosynthetic relatives (plastids) are directly or indirectly evolved through a single endosymbiotic event (Reyes-Prieto et al. 2007, Gould et al. 2008, Archibald 2009). Through this primary (original) endosymbiosis, cyanobacterium invokes the development of the plastids (primary plastids) in divisions of Glaucophyta, Rhodophyta (red algae) and Viridiplantae (green algae and land plants) that are placed in the Archaeplastida.

Figure 1.2: Current reorganization of super-groups in the domain Eukarya (Based on Gould et al. 2008; Achibald 2009).

Then a later subsequent endosymbiotic incident invoking the integration of eukaryotic algae into other eukaryotes, led to the development of all other plastids; that existed in Chromalveolata (kelps, dinoflagellates and malaria parasites), Excavata (euglenids) and Rhizaria (chlorarachniophytes) (Archibald 2012, Ball et al. 2011). The super group Archaeaplastida comprises only of the organisms with primary plastids, while secondary and tertiary plastids primarily exist in the members of the Chromalveolata (Cryptophyta, Stramenopiles, Haptophyta, Apicomplexa, Chromerida and certain Dinoflagellata), Excavata (Eugleonophyta) and Rhizaria (Chlorarachniophyta) (Fig. 1.2). The presence of plastid-lacking organisms is more surprising and confusing, it could be possible they never had plastids or lost their plastids.

Based on the recent phylogenetic analyses on the host level, the group Stramenopiles is placed together with the Alveolata (includes Chromerida, Apicomplexa and Dinoflagellata) and Rhizaria (includes Chlorarachniophyta that have green-plastids), these groups are collectively abbreviated as SAR. Haptophyta (group Chromalveolata) which is considered as a sister group to the SAR; and Cryptophyta was found to be more close to the group Viridiplantae (Burki et al. 2012), while the Euglenophyta (group Excavata) was distantly related to the above mentioned groups.

Based on the phylogenetic analyses on the plastid level, there are evidences of secondary endosymbiotic events from either a Chlorophyta (green lineage) or a Rhodophyta (red lineage), but there are no reports of endosymbiotic events from a Glaucophyta. Chlorophyta, the green lineage undergoes two independent endosymbiotic events, where members of core families UTC (Ulvophyceae,Trebuxiophyceae, Chlorophyceae) and Prasinophyceae family leads to the origin of the Chlorarachniophyta (Rhizaria) and Euglenophyta (Excavata), respectively (Rogers et al. 2007, Turmel et al. 2009). While it is correct that no close relation was found between the host of Rhizaria and Excavata, from which they originated, but there is much closeness in genes of their individual chloroplasts (Archibald 2009, Keeling 2010). The Rhodophyta, the red lineage was further diversified and found in various groups including the Cryptophyta, Haptophyta, Stramenopiles, Apicomplexa and Chromerida. Based on the genetic and phenotypic evidence, it was established that all plastids of these groups arose from the same ancestral red lineage (Bodył et al. 2009, Keeling 2010); but there are still unresolved issues about the exact circumstances of this event.

The group Pyrrophyta (dinoflagellates) has the presence of different plastids that originated from various lineages such as Chlorophyta, Cryptophyta, Stramenopiles (heterokontophyta) and Haptophyta. It is suggested that there may be two explanations for this acquisition: (a) either a tertiary endosymbiotic event occurs between a heterotrophic eukaryote and a secondary plastid-containing alga, leading to the origin of these different plastids; (b) or a sequential secondary endosymbiotic event occurs, in which acquired secondary plastids were lost out and they are replaced by a primary plastid-containing alga endosymbiotically.

Phylogeny and Classification

It is now understood that algae are not evolved as a cohesive, natural assemblage of organisms and their positions are usually dependent on problematic interpretations of the data related to groups of algae. There are placed in as many as seven (Andersen 1992), eight (O’Kelley 1993) or more eukaryotic and one or more eubacterial lines within the domains Eukarya and Bacteria (Woese et al.1990). Van den Hock et al (1994) recognized about 10 of the divisions which represent almost all the groups of algae existing or are known to the scientific communities (Table 1.1).

| Divison (common name) and distinguishing features | Major groups (common name and/or features) | Distribution of microscopic species | Representative genera |

|---|---|---|---|

| | |||

| Cyanophyta (Blue-green algae) Chlorophyll a,d; phyobilins; β-carotene; zeaxanthin; echinenone; canthaxanthin; myxoxanthophyll, 3 minor xanthophylls, oscillaxanthin,; prokaryotic; Gram-negative cell wall | Chroococcales (Unicellular cocci and rods; Binary fission and budding | Terrestrial, freshwater, marine, symbiotic | Microcystis, Synechococcus, Synecliocystis |

| Pleurocapsales (Unicellular and aggre... | |||

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contents

- 1. Microalgae I: Origin, Distribution and Morphology

- 2. Microalgae II: Cell Structure, Nutrition and Metabolism

- 3. Microalgae III: Stress Response and Wastewater Remediation

- 4. Municipal Wastewater

- 5. Petroleum Wastewater

- 6. Distillery and Sugar Mill Wastewater

- 7. Tannery Wastewater

- 8. Pulp and Paper Wastewater

- 9. Textile Wastewater

- 10. Food Processing Wastewater

- 11. Integrated Microalgal Wastewater Remediation and Microalgae Cultivation

- 12. Microalgal Biomass: An Opportunity for Sustainable Industrial Production

- Index