- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Digital Mapping and Indigenous America

About this book

Employing anthropology, field research, and humanities methodologies as well as digital cartography, and foregrounding the voices of Indigenous scholars, this text examines digital projects currently underway, and includes alternative modes of "mapping" Native American, Alaskan Native, Indigenous Hawaiian and First Nations land. The work of both established and emerging scholars addressing a range of geographic regions and cultural issues is also represented. Issues addressed include the history of maps made by Native Americans; healing and reconciliation projects related to boarding schools; language and land reclamation; Western cartographic maps created in collaboration with Indigenous nations; and digital resources that combine maps with narrative, art, and film, along with chapters on archaeology, place naming, and the digital presence of elders.

This text is of interest to scholars working in history, cultural studies, anthropology, Native American studies, and digital cartography.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1Alive with Story

Introduction

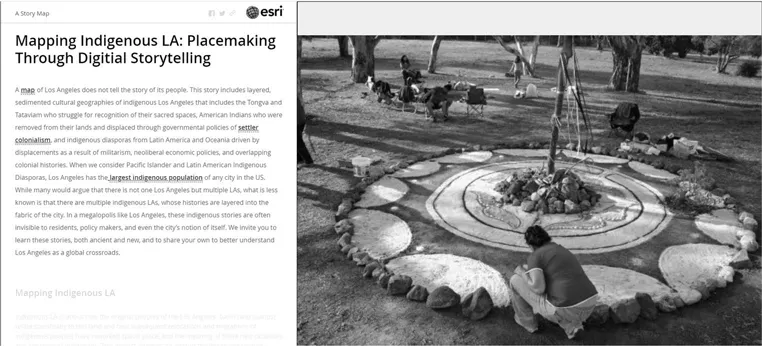

Land is Life: Mapping Indigenous LA

Source Materials

Resources and Pedagogical Materials

Challenges

Remapping Return: Carrying Our Ancestors Home

Source Materials

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Digital Mapping—Ethics, the Law, and the Sacred

- 1 Alive with Story: Mapping Indigenous Los Angeles and Carrying Our Ancestors Home

- 2 Digitally Re-Presenting the Colonial Archive: Resources for Researching and Teaching the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and the Native American Boarding School Movement

- 3 Access to Truth, Healing, and Justice: Digitizing the Records of U.S. Indian Boarding Schools

- 4 The Indigenous Digital Archives: Creating Effective Access to and Collaboration with Government Records

- 5 Myaamiaataweenki Eekincikoonihkiinki Eeyoonki Aapisaataweenki: A Miami Language Digital Tool for Language Reclamation

- 6 A Cartographic History and Analyses of Indian-White Relations in the Great Plains

- 7 Mapping with Indigenous Peoples in Canada

- 8 Early California Cultural Atlas: Visualizing Uncertainties Within Indigenous History

- 9 Access to Government Information and Inclusive Stewardship of North America’s Archaeological Heritage

- 10 Finding Balance Between Development and Conservation: The O‘ahu Greenprint

- 11 Native Land: Social Media Education and Community Voices

- 12 Mapping Indigenous American Cultures and Living Histories (MIAC-LH): A Gathering Place

- 13 William Commanda, Oral Wampum Storytelling, Digital Technology and Remapping Indigenous Presence Across North America

- 14 Indigenous Place Names as Visualizations of Indigenous Knowledge

- Appendix

- Index