![]()

Chapter 1 Introduction

Mike Parker Pearson and Helen Smith

Introduction

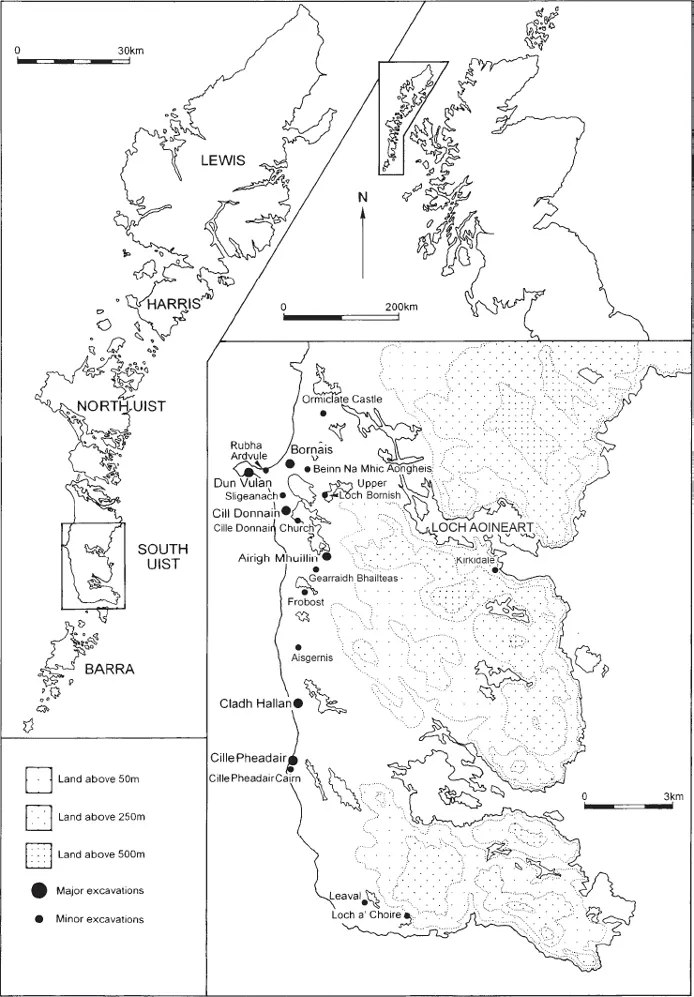

The SEARCH project (Sheffield Environmental and Archaeological Research Campaign in the Hebrides) commenced in 1987 and covered the southern islands of Scotland’s Western Isles, also known as the Outer Hebrides. One team, led by Keith Branigan, Pat Foster and Colin Merrony, concentrated their research on Barra and the small isles at the southernmost end of the island chain (Branigan 2005; Branigan and Foster 1995; 2000; 2002) and another team was based on South Uist (Figure 1.1; Parker Pearson et al. 2004). A third team carried out an integrated series of environmental projects investigating palynology, vegetation, palaeoentomology, dune geomorphology, climate change, phytoliths, animal husbandry, crop processing and related fields across South Uist and Barra (Gilbertson et al. 1996).

The first major excavation carried out by the SEARCH project on South Uist was the rescue excavation of what was thought to be a shell midden at Cill Donnain, directed by Marek Zvelebil in 1989–1991 (Zvelebil 1989; 1990; 1991).1 Lasting three summer seasons, the excavation revealed the remains of a circular, stone-walled house dating to the Iron Age and known as a wheelhouse. This term refers to the plan of these distinctive Hebridean roundhouses – the interior is sub-divided by stone piers forming a radial plan so that, from above, they resemble the spokes of a wheel. Wheelhouses are known only in the Outer Hebrides and Shetland (Crawford 2002); many have been excavated in the last century or so by archaeologists. Wheelhouses were used as dwellings and provide evidence of daily life in the period c.300 BC – AD 500 (the end of the Early Iron Age, the Middle Iron Age and the beginning of the Late Iron Age). Buried beneath the Cill Donnain wheelhouse lay the remains of a Bronze Age settlement, partly investigated by Zvelebil in 1991 and further explored by Mike Parker Pearson and Kate MacDonald in 2003.

The geology and soils

The Outer Hebrides are situated 60–80km off the northwest coast of Scotland, separated from the mainland by The Minch in the north and the Sea of the Hebrides in the south. Forming a breakwater against the Atlantic, the Outer Hebrides provide some shelter to the Inner Hebrides, situated to the east, and to the Scottish mainland, from Cape Wrath in the north to Ardnamurchan in the south. The archipelago of the Western Isles stretches 213km from the Butt of Lewis to Barra Head, and consists of 119 named islands, of which only 16 are now permanently inhabited (Boyd 1979). The island chain, once known as ‘The Long Island’ (Carmichael 1884), divides geographically into two main groups, the Sound of Harris separating Lewis and Harris (total area c.214,000 ha) from the southern islands, namely North Uist, Benbecula, South Uist and Barra (total area c. 76,000 ha).

South Uist (Uibhist a Deas) is an island 30km north–south and 12km east–west. To the north of it lies Benbecula and, beyond, North Uist. To the south, beyond the island of Eriskay (Eirisgeigh) and a number of small, uninhabited islands, are Barra and the southern isles.

The Outer Hebrides were formed over 3,000 million years ago from an eroded platform of Precambrian Lewisian gneiss whose primary components are quartz and mica. This forms a mountainous band on the islands’ eastern seaboard. On the west coast the sea bed is shallow, owing to a submerged platform forming an extensive area of continental shelf. In the Uists, the glacial deposits are now eroded in places or overlain by peat, particularly in the upland regions in the east, and divided by oligotrophic freshwater lochs. On the western seaboard, the glacial deposits and peat are overlain by highly calcareous windblown sand, forming dune systems and sandy plains with eutrophic lochs (Boyd and Boyd 1990).

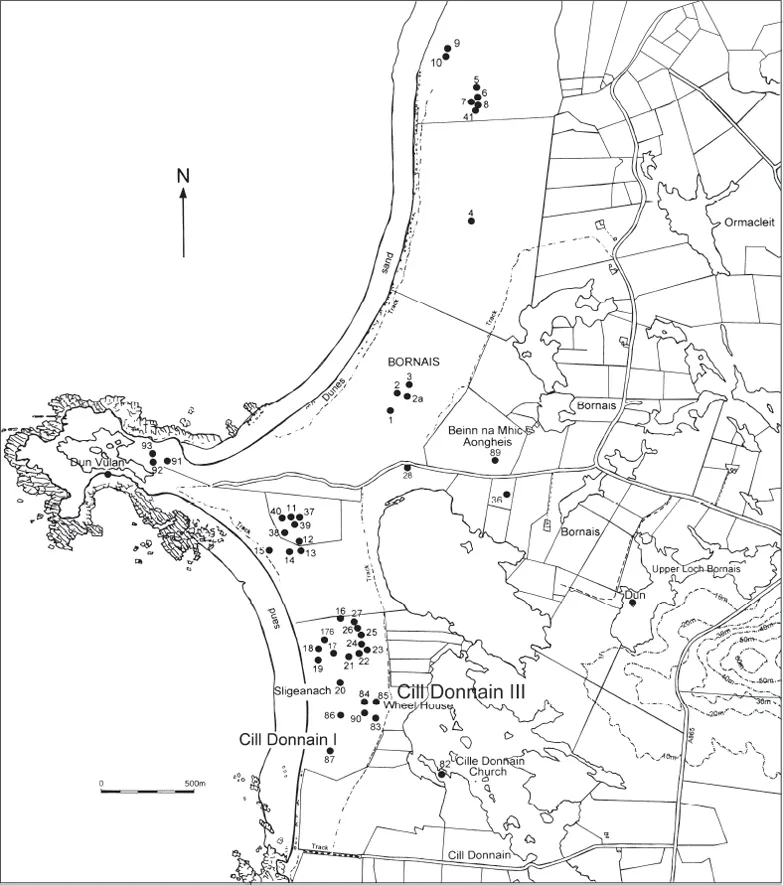

Figure 1.1 Map of South Uist, showing Cill Donnain III and other archaeological sites investigated by the SEARCH project and its successors

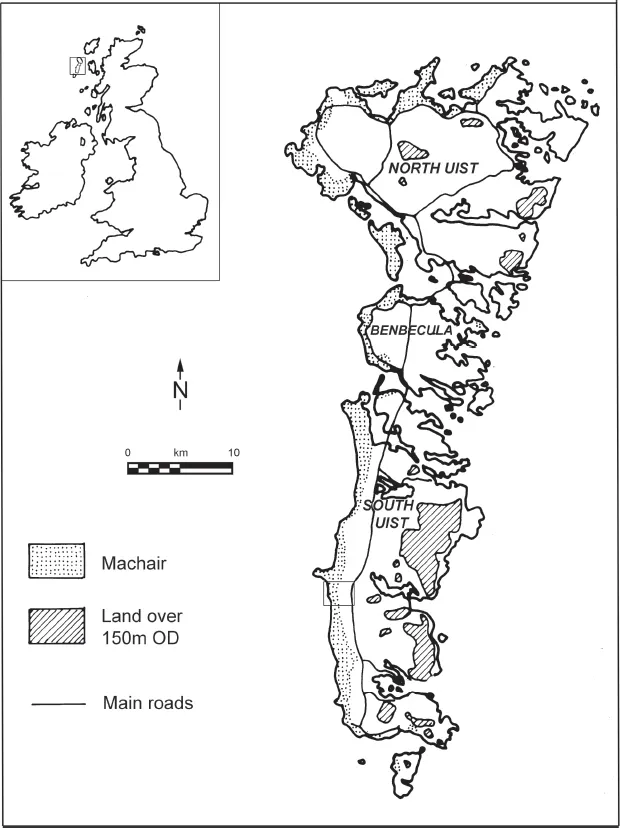

Figure 1.2 Map of the Uists, showing the areas of west-coast machair, with the position of Figure 1.5 also marked

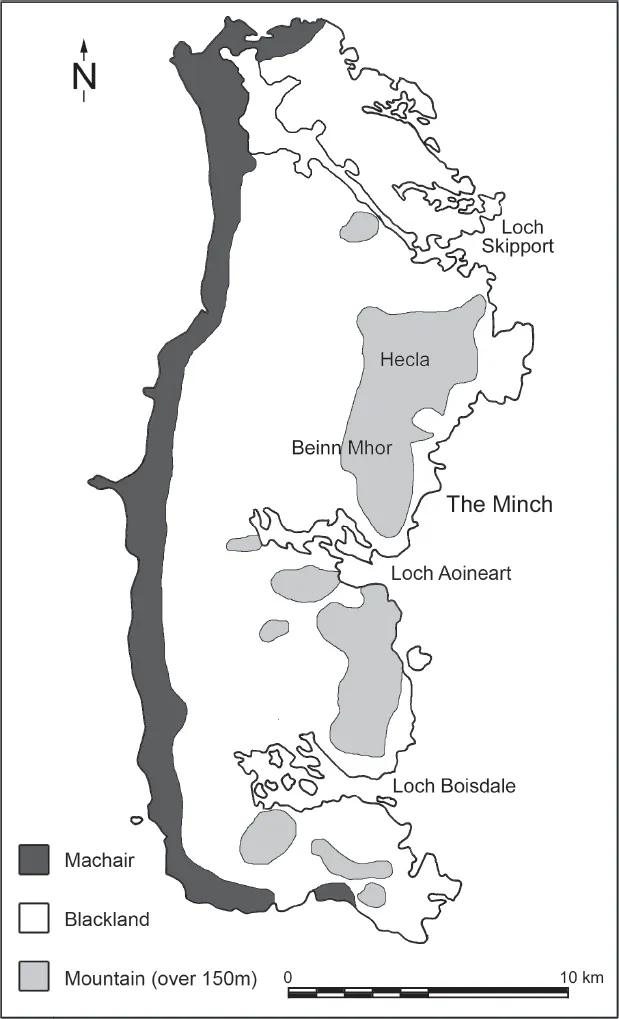

The southern Outer Hebrides can be divided into three broad zones of soil types. On South Uist (Figure 1.2), the eastern third is the hilly and mountainous area that comes down to the sea in a series of three fjord-like sea lochs separated by a rugged coastline of low cliffs. The middle zone is an area of shallow peat soils, known as ‘blackland’, interspersed with myriad small freshwater lochs. To the west, the sea covers the shallow shelf that stretches out for about 20km from the coastline. This was formerly dry land in the Mesolithic and Early Neolithic but has since become inundated. The most distinct landform of South Uist and the Western Isles is the zone of calcareous sand that covers the island’s west coast and is known as machair. With the associated dune systems, the machair covers approximately 120 square kilometres along the west coast of North Uist, Benbecula and South Uist. The machair forms an almost continuous fertile strip along this exposed Atlantic coast. It supports grass vegetation and extends inland for about a kilometre along the west coast of South Uist; small pockets of machair can also be found on Barra and on the north and south coasts of the Uists and Benbecula (Figures 1.2–1.3).

Figure 1.3 The machair and other landscape zones of South Uist

The machair, therefore, comprises grassland formed on gently sloping shell-sand deposits. The nature and evolution of machair formation is discussed in detail by Ritchie and colleagues (1976; 1979; 1985; Ritchie and Whittington 1994; Ritchie et al. 2001; Edwards et al. 2005). Large quantities of shell sand were swept landwards, aided by rising sea level, to form an extensive pre-machair dune system. High-energy waves and strong Atlantic winds caused the deflation of beach dunes and swept sand inland. Where the sand stabilized, calcophile grassland established to form long stretches of sandy machair plain. Ritchie (1979: 115–17) suggested that sand deposition might have begun as early as 3750 BC, with primary deposition from 3000 cal BC to 2500 cal BC, followed by stabilization in the Beaker period (2400–1800 cal BC). More recently, Edwards et al. (2005) have discovered that machair sand began to form from at least the mid-eighth millennium BP (c.5500 BC; see also Ritchie 1985; Ritchie and Whittington 1994). However, the complete absence of Mesolithic and Neolithic settlement sites on the machair shows that it had not stabilized until the end of the third millennium BC.

Figure 1.4 Map of archaeological sites in the Cill Donnain area; site 85 is the Cill Donnain III wheelhouse

The calcareous soils of the machair have high pH values, 6.5 to 7.5 in top soils and 7.5 to 8.0 in subsoils. The dune-machair soils range from calcareous regosols and brown calcareous soils to poorly drained calcareous gleys and peaty calcareous gleys, depending on the drainage conditions and level of the water table (Glentworth 1979; Hudson 1991). Water percolating from the freely draining sands has contributed to the formation of lochs and fens in the slack behind the machair. Areas of machair are prone to seasonal flooding (see Sharples 2012b: figs 139–140).

The SEARCH project

The main aim of the SEARCH project was to investigate the long-term adaptation of human societies to the marginal environment of the Outer Hebrides. Sheffield University’s Department of Archaeology and Prehistory2 was at the forefront of environmental and processual archaeology in the 1970s and 1980s and this was an opportunity to ground models of human–environment interaction, cultural adaptation to natural constraints, and long-term processes of culture change in a field project in which most of the staff and students of the department collaborated as a joint venture.

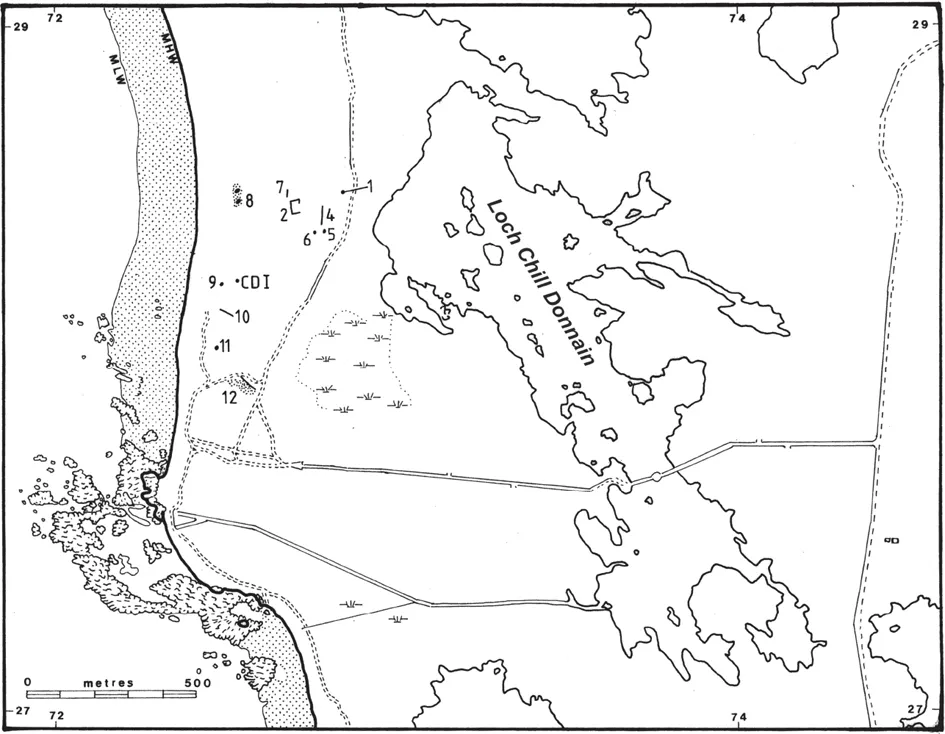

Figure 1.5 Archaeological remains mapped in 1989 on Cill Donnain machair. CDI is the Early Bronze Age site of Cill Donnain I; 1 is the Cill Donnain III wheelhouse; 2, 4, 7 and 10 are field walls; 5, 6 and 11 are stone structures; 8 is an eroding structure; 9 was (erroneously) identified as a stone ‘cist’; 12 is structure/walls (?)

Initial survey work was carried out in 1987 by Martin Wildgoose, Richard Hodges and David Gilbertson. Wildgoose identified a number of midden sites on the South Uist machair, three of which were eroding and were thus targeted for excavation. One of these was Cill Donnain III, the subject of this report. After excavation in 1989–1991, the surviving walls of the Cill Donnain wheelhouse were moved in 1992 to the grounds of Taightasgaidh Chill Donnain (Cill Donnain Museum) where they were re-erected under Marek Zvelebil’s supervision.

The site setting

The Cill Donnain wheelhouse site (known as Cill Donnain III or site 85 of the machair survey; Parker Pearson 2012c) is located on South Uist’s machair at NF 7284 2857 (Figure 1.4). The site lies on the eastern edge of a large sand valley or ‘blow-out’ among the dunes, within 100m of the western shore of Loch Chill Donnain (Figures 1.5–1.8). It lies on the gentle eastern slope of the blow-out, at the foot of a high, steep-sided dune whose flat summit provides excellent views of the surrounding machair (Figure 1.9). This dune probably formed within the last thousand years because there is compelling evidence that it sits on top of a large archaeological site, the northern edge of which has been detected at the base of the dune’s north side. The remains of Norse-period settlement emerging beneath the southeast side of this dune indicate that the windblown sand accumulated at some time after about AD 1200. Coring with a soil auger in 2003 revealed that the Iron Age deposits, of which the wheelhouse formed a part, continue eastwards beneath the large dune.

Figure 1.6 Cill Donnain III at the start of excavations in 1989 in the sand blow-out on the west side of the dune, seen from the north

Archaeological finds have been made on the machair of Cill Donnain for many years. In the 1960s, Coinn...