- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

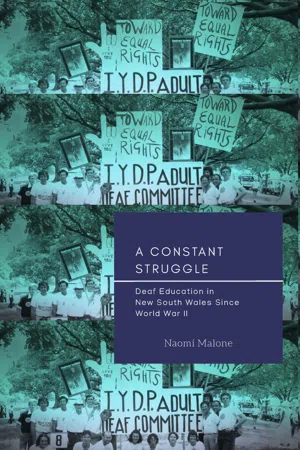

Deaf education in New South Wales has made tremendous progress since the end of World War II, yet issues remain for students from their early years of education through secondary high school. Naomi Malone traces the roots of these issues and argues that they persist due to the historical fragmentation within deaf education regarding oralism (teaching via spoken language) and manualism (teaching via sign language). She considers the early prevalence of oralism in schools for deaf students, the integration of deaf students into mainstream classrooms, the recognition of Australian Sign Language as a language, and the growing awareness of the diversity of deaf students. Malone's historical assessments are augmented by interviews with former students and contextualized with explanations of concurrent political and social events. She posits that deaf people must be consulted about their educational experiences and that they must form a united social movement to better advocate for improved deaf education, regardless of communication approach.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Constant Struggle by Naomi Malone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

International Developments: A Historical Outline of Deaf Education

Few records about deaf people were kept from ancient times until the sixteenth century, so no one knows how deaf people were educated during these times. However, the very few existing records show that deaf people experienced a variety of perceptions and attitudes from the communities in which they lived and from their families.1 These perceptions and attitudes shaped the ways in which deaf people were, or were not, educated.

Early records pertaining to the deaf experience show the role of signs and gestures in the daily life of deaf people, prompting contemplation about the extent to which deaf people were perceived as being able to communicate and reason in ancient times. Plato’s Cratylus, 360 BC, includes a discussion between Hermogenes and Socrates, which raised a question about the use of signs as a form of communication between deaf people:

SOCRATES: And here I will ask you a question: Suppose we had no voice or tongue, and wanted to indicate objects to one another, should we not use, like the deaf and dumb, make signs with the hands, head and the rest of the body?

HERMOGENES: How could it be otherwise, Socrates?

SOCRATES: We should imitate the nature of the thing; the elevation of our hands to heaven would mean lightness and upwardness; heaviness and downwardness would be expressed by letting them drop to the ground; if we were describing the running of a horse, or any other animal, we should make our bodies and their gestures as like as we could to them.2

In ancient Egypt, there was general acceptance of people with disabilities. Deaf people were considered to be especially selected by the gods because of their communicative behavior due to not being able to hear and their desire to communicate. As a consequence, they were treated respectfully and educated, usually through the use of hieroglyphs and gesture signs.3 In ancient Greece, despite a general hostility toward people with disabilities, some individuals with disabilities lived in Greek society. In 7 BC, the orator M.V. Corvinus had a deaf relative who received instruction in painting.4 Greek philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle held certain views about deaf people. Plato’s belief of innate intelligence—whereby intelligence was present at birth—was considered the norm. Only time was required for the demonstration of outward signs of intelligence through speech. People who were deaf and could not speak were considered incapable of rational thoughts and ideas.5

Aristotle, a prominent philosopher during his time (384–322 BC), argued that deaf people were incapable of reasoning; hence, they were incapable of receiving education: “Men that are born deaf are in all cases also dumb; that is, they can make vocal sounds, but they cannot speak.”6 According to Aristotle, people with the inability to hear could not learn because they could not hear. Since the Greek language was regarded as the perfect language, people who did not speak Greek—including deaf people—were considered Barbarians.7 Because Aristotle was well regarded in his society, his theory was adopted, leading to deaf people to be not educated. The idea of not educating deaf people remained unchallenged until the sixteenth century.8

In ancient Rome, as in ancient Greece, there were exceptions to the general nonacceptance of people with disabilities. In the first century AD, there is evidence of an influential parent seeking assistance for a deaf child. In Natural History, Pliny the Elder mentions Quintus Pedius, the deaf son of a Roman consul. The father managed to seek permission from Emperor Augustus for his son to become an artist. Pedius then went on to become a successful painter.9 It is assumed that Pedius received instruction in the art of painting. This is supported by the following quote:

. . . I must not omit, too, to mention a celebrated consultation upon the subject of painting, which was held by some persons of the highest rank. Quintus Pedius, who has been honored with consulship, and who had been named by Dictator Ceasar as co-heir with Augustus, had a grandson, who being dumb from birth, the orator Messala, to whose family his grandmother belonged, recommended that he should be brought up as a painter, a proposal which was approved by the late Emperor Augustus. He died, however, in his youth, having made great progress in art.10

In reference to theological literature, the Talmud—the rabbinical teachings and Jewish oral law begun in the fifth century AD—suggested the possibility of educating deaf children because they were children of God. Christianity raised new perspectives on the injustice of neglecting deaf people. In the fourth century AD, Saint Jerome’s interpretation of the Vulgate discussed deafness and the possibility of salvation through signed and written communication. He viewed “the speaking gesture of the whole body” as serving to communicate the word of God in addition to speech and hearing. Saint Augustine, who wrote De Quantitate Animae and De Magistro, discussed signs and gestures as an alternative to spoken language in the communication of ideas and in learning the Gospel:11

Have you not seen men when they discourse, so to speak, by means of gestures with those who are deaf, the deaf likewise using gestures? Do they not question and reply and teach and indicate everything they wish or at least a great many things? When they use gestures they do not merely indicate visible things, but also sounds and tastes.12

THE MIDDLE AGES

The following ten centuries provide very little evidence that might assist in understanding the lives of deaf people and their education. One can only assume that the Middle Ages, which include the Dark Ages to the mid-eleventh century, might have been a particularly dark time for deaf people. Mystical and magical cures for deafness were common, highlighting the range of beliefs people held about deafness or hearing loss. One such example was expressed by Saint Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179): “Deafness may be remedied by cutting off a lion’s right ear and holding it over the patient’s ear just long enough to warm it and to say, ‘Hear adimacus by the living God and the keen virtue of a lion’s hearing.’”13

During the Middle Ages, deaf people were denied the right to marry, to celebrate Mass, and to claim inheritance. Regardless, examples of deaf people being educated have been recorded. Venerable Bede, a Saxon monk, wrote about Bishop Hagulstad, otherwise known as St. John of Beverley, teaching a dumb14 youth to speak in 712 AD.15 This enabled some people to accept the fact that deaf people could be taught to speak, and St. John continued to teach the youth by an oral method using repetition of letters, syllables, words, and sentences. He eventually became the patron saint of teachers of the deaf.16

THE RENAISSANCE

After the Middle Ages, the Renaissance ushered in an era of revival of classical art, literature, and learning. Some indication of attitudes toward deaf people in this period may be found in the writings of Leonardo da Vinci, Dutch humanist Rudolphus Agricola, and the Italian mathematician and physician Girolamo Cardano. Agricola and Cardano played a role in generating awareness of the potential of deaf people’s ability to learn.17

In 1499, Leonardo da Vinci referred to lipreading in his written works Precepts of the Painter, as published in the passage Of Parts of the Face.18 Agricola’s 1528 work, De Inventione Dialecta, described a deaf person who had been taught to read and write.19 He advocated the theory that the ability to use speech was separate from the ability of thought.20 Agricola’s work fell into the hands of Cardano, who mused upon the ability of deaf people being able to “speak by writing” and “hear by reading,” and described how deaf people may conceive words and associate them directly with ideas.21 Cardano was not necessarily a professional teacher of the deaf but became involved in deaf education due to his personal experience as a parent of a unilaterally deaf son. He challenged Aristotle’s theory,22 recognizing that deaf people could reason while advocating that they be taught to read and write and that abstract ideas be conveyed through signs.23

The mid-fifteenth century saw the introduction of the printing press, a significant invention that dramatically affected all societies throughout the world. This included deaf people. The printing press enabled teachers and literate parents of deaf children to read about each other’s experiences with deaf students and children in published works. The increasing availability of published works strongly encouraged societies to use the written word to communicate and reduce reliance on the spoken word. This spread of the written word enabled deaf people to rely upon and use written language as used by hearing people for their education24 and to enjoy the “enhanced benefits that came with an understanding of words.”25

The emergence of Spain as a powerful nation influenced the lives and education of deaf people. During the sixteenth century, methods of education for deaf people were influenced by laws for deaf people in Spain. In 1578, the great advocate of deaf people, Pedro Ponce de Leon, described how he taught the congenitally deaf sons of lords and other notables to read and write; to gai...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Abbreviations

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. International Developments: A Historical Outline of Deaf Education

- 2. Speech Is the Birthright of Every Child: Oralism in NSW from the 1940s to the 1960s

- 3. The March of Integration: The 1970s

- 4. Mainstreaming and Auslan: The 1980s

- 5. A New Era in Deaf Education in Australia: The 1990s

- 6. Diversity: The 2000s

- 7. A True Consumer Organization: 2010 and Beyond

- Conclusion: “In Pursuit of Better Outcomes”

- Bibliography

- Index