- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

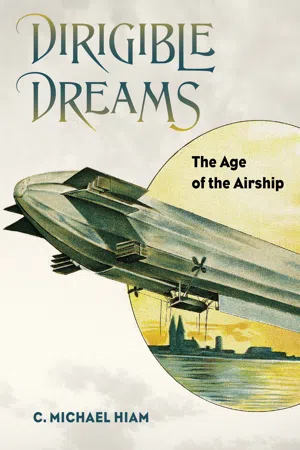

Here is the story of airships—manmade flying machines without wings—from their earliest beginnings to the modern era of blimps. In postcards and advertisements, the sleek, silver, cigar-shaped airships, or dirigibles, were the embodiment of futuristic visions of air travel. They immediately captivated the imaginations of people worldwide, but in less than fifty years dirigible became a byword for doomed futurism, an Icarian figure of industrial hubris. Dirigible Dreams looks back on this bygone era, when the future of exploration, commercial travel, and warfare largely involved the prospect of wingless flight. In Dirigible Dreams, C. Michael Hiam celebrates the legendary figures of this promising technology in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—the pioneering aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont, the doomed polar explorers S. A. Andrée and Walter Wellman, and the great Prussian inventor and promoter Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, among other pivotal figures—and recounts fascinating stories of exploration, transatlantic journeys, and floating armadas that rained death during World War I. While there were triumphs, such as the polar flight of the Norge, most of these tales are of disaster and woe, culminating in perhaps the most famous disaster of all time, the crash of the Hindenburg. This story of daring men and their flying machines, dreamers and adventurers who pushed modern technology to—and often beyond—its limitations, is an informative and exciting mix of history, technology, awe-inspiring exploits, and warfare that will captivate readers with its depiction of a lost golden age of air travel. Readable and authoritative, enlivened by colorful characters and nail-biting drama, Dirigible Dreams will appeal to a new generation of general readers and scholars interested in the origins of modern aviation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dirigible Dreams by C. Michael Hiam in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

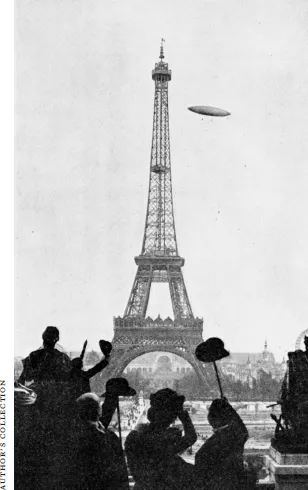

As enthusiastic supporters of the aeronaut’s experiments, Parisians welcomed his newest creation, “Santos-Dumont Number 5,” and early one quiet Saturday morning, July 13, 1901, No. 5 started off from the Parc d’Aérostation at Saint Cloud in the direction of the Eiffel Tower. At the controls stood the airship’s designer and sole occupant, Alberto Santos-Dumont, while the Scientific Commission of the Aéro Club watched from the ground. Santos-Dumont reached the tower, about three and a half miles distant, in ten minutes, and, cautiously circumventing the structure, set a course back to Saint Cloud. Having made good speed thus far and cruising safely over the chimney pots and steeples of Paris, he had minutes to spare, but then, in the homestretch, No. 5 faced stubborn headwinds that proved too much for its sixteen-horsepower motor. Knowing he would not be awarded the Deutsch Prize that day, a frustrated Santos-Dumont passed over the upturned heads of the Scientific Commission at an altitude of 660 feet, the thirty-minute time limit allotted for the sortie having long since elapsed.

“Just at this moment,” Santos-Dumont recalled of what happened next, “my capricious motor stopped, and the airship, bereft of its power, drifted until it fell on the tallest chestnut tree in the park of M. Edmond de Rothschild.”2 Inhabitants and servants ran out of the villa toward the stricken No. 5, and there they saw Santos-Dumont marooned on high. Nearby lived the Princess Isabel, Comtesse d’Eu, exiled heir to the Brazilian throne, and she sent a champagne lunch up to her compatriot with an invitation to, after he got down, come tell her of his trip. “When my story was over,” he recalled, “she said to me: ‘Your evolutions in the air made me think of the flight of our great birds of Brazil. I hope that you will succeed for the glory of our common country.’”3

The Scientific Commission reassembled less than a month later, this time at 6:30 a.m., and its members again watched as Santos-Dumont flew toward the Eiffel Tower in his quest for the Deutsch Prize, named for the petroleum magnate and aviation enthusiast, Henri Deutsch de la Meurthe, who promised 100,000 francs to the first person to fly from Saint Cloud to the Eiffel Tower and back. The Brazilian aeronaut reached his goal in nine minutes—sixty seconds faster than his previous attempt, although along the way No. 5 had begun a slow descent because hydrogen had started to leak out from somewhere in the ellipsoidal-shaped gasbag. Ordinarily, Santos-Dumont would have come to earth immediately, but to do so would have meant abandoning the prize, and therefore he took the risk of going on. Again he successfully rounded the tower, although now his gasbag had shrunk visibly and, with the fortifications of Paris near La Muette beneath him, the suspension wires holding the keel of the craft to the gasbag had begun to sag. Some of the wires caught the propeller. “I saw the propeller cutting and tearing at the wires,” he said. “I stopped the motor instantly. Then, as a consequence, the airship was at once driven back toward the Tower by the wind, which was strong.”

Santos-Dumont always dreaded the prospect of being dashed against the Eiffel Tower in one of his airships and falling, he fretted, “to the ground like a stone,” and so he frantically searched for a place to land. However, with No. 5 fast losing hydrogen, chances to do so appeared slim. “The half-empty balloon,” he said of the gasbag above him, “fluttering its empty end as an elephant waves his trunk, caused the airship’s stem to point upward at an alarming angle. What I most feared, therefore, was that the unequal strain on the suspension wires would break them one by one and so precipitate me to the ground.”

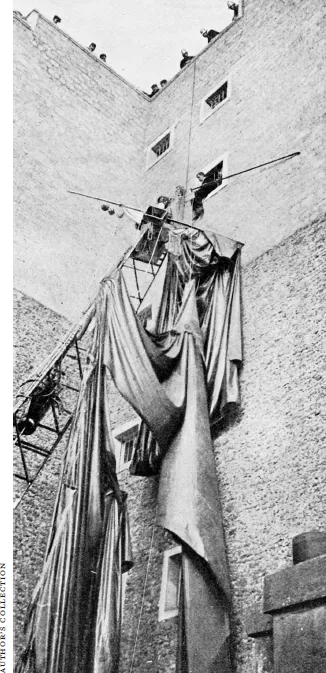

He thought he could fly clear of the building immediately in front of him, the Trocadéro Hotel, and settle his craft on the Seine embankment just beyond, but instead he descended to about a hundred feet and hit the hotel roof, rupturing the bag. “This was the ‘terrific explosion,’” he said, “described in the newspapers of the day.” Santos-Dumont and his No. 5 tumbled into a deep courtyard, but before hitting the ground the keel of the craft, a sixty-feet-long framework of curved pine scantlings and aluminum joints, fortuitously wedged itself at a forty-five-degree angle between a side wall and scaffolding beneath. The Brazilian aeronaut, perched fifty feet from the ground and balancing precariously on his overturned basket, managed to climb onto an adjacent windowsill where, once again, he found himself marooned on high. “After what seemed like tedious waiting,” he said, “I saw a rope being lowered to me from the roof above. I held to it and was hauled up, when I perceived my rescuers to be the brave firemen of Paris. From their station at Passy they had been watching the flight of the airship. They had seen my fall and immediately hastened to the spot.” It had been a close call, and Santos-Dumont admitted as much. “The remembrance of it,” he said, “sometimes haunts me in my dreams.”

Before he began experimenting with dirigibles, Santos-Dumont had designed a balloon of the free-floating, rotund type and called it Brazil, after his native country. Compared to the other balloons then flying over Paris, Brazil was a speck of a thing, a scant twenty feet in diameter and, even when deflated, as light as a feather. Santos-Dumont, himself diminutive at five feet, five inches and—he claimed—110 pounds, used very thin but very strong Japanese silk to hold the balloon’s 4,104 cubic feet of hydrogen. He also did everything else he could to keep the Brazil extremely light. The varnished silk envelope weighed only thirty-one pounds, the balloon’s basket just thirteen pounds, the guide rope seventeen and a half pounds (yet was a hundred yards long), and the grappling iron a mere six and a half pounds. Despite the misgivings of experts, Santos-Dumont’s little balloon proved successful. “The ‘Brazil’ was very handy in the air, easy to control,” he said of his aerial runabout. “It was easy to pack also, on descending; and the story that I carried it in a valise is true.”

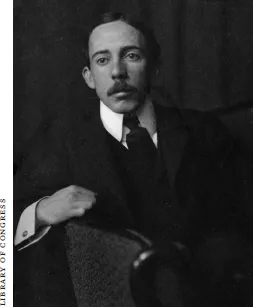

Alberto Santos-Dumont.

To reinflate the Brazil he would need hydrogen, a gas relatively simple to make and praised by aeronauts because of its natural buoyancy. Fifteen times lighter than air, when hydrogen is trapped inside a balloon it can lift impressive loads. The gas expands and contracts with changes in atmospheric pressure and air temperature, but at sea level and at sixty degrees Fahrenheit a cubic foot of hydrogen will lift a little more than an ounce. Under these conditions, therefore, to loft Santos-Dumont’s 110 pounds required 1,760 cubic feet of hydrogen, meaning that his Brazil, with a capacity of 4,104 cubic feet, was more than adequate for the job. Hydrogen, of course, did have and still has one very severe drawback: its enormous explosive potential when mixed with oxygen. Many an unlucky aeronaut in Santos-Dumont’s day met a ghastly end—often luridly depicted in the illustrated newspapers—through hydrogen explosions. Although acutely aware of this danger, he, like all aeronauts, stuck with hydrogen because there was no better substitute, hot air having far less lifting force and requiring that a flame be kept on board, while the nonflammable helium was still decades away.

Santos-Dumont and his No. 5 rounding the Eiffel Tower, July 13, 1901.

No. 5 with its keel wedged in the courtyard and its gas bag in shreds.

Prior to his first flight in the Brazil, Santos-Dumont had made, by his estimate, about thirty ascents in other balloons, and the most memorable flights at night. “One is alone in the black void,” he rhapsodized of his nocturnal jaunts, “in a murky limbo where one seems to float without weight, without a surrounding world, a soul freed from the weight of matter! There is a flash upward and a faint roar. It is a railway train, the locomotive’s fires, maybe, illuminating for a moment its smoke as it rises. Then, for safety, we throw out more ballast and rise through the black solitudes of the clouds into a soul-lifting burst of splendid starlight. There, alone in the constellations, we await the dawn!”

The aerial explorer admitted that balloons were his obsession, and that he had the money to indulge in them. (The family plantation back in São Paulo had four million coffee trees and 9,000 laborers, not to mention factories, docks, ships, and 146 miles of private railroad line.) “Some of these spherical balloons I rented,” Santos-Dumont explained of his hobby. “Others I had constructed for me. Of such I have owned at least six or eight.”4 Still, even with his great wealth, it took Santos-Dumont a long time before he could overcome his aversion to the costly “honorarium”5 demanded by Parisian aeronauts for even the shortest of ascents.

It was in a Rio bookshop one day in 1897, while he was buying things to read for his second sea voyage to France, that Santos-Dumont, aged twenty-five, came across an account of Andrée and the giant polar balloon. Intrigued, when he arrived in Paris the young man sought out the balloon’s builder, Henri Lachambre, and asked how much it would cost to be taken up. Lachambre, perhaps moved by the youthful Brazilian’s enthusiasm, quoted a reasonable price. At the appointed day and hour Lachambre’s colleague, Alexis Machuron (just returned from the Arctic after inflating the Swedish aeronaut Andrée’s balloon) gave the order “Let go all!” and instantly Machuron and his passenger were airborne.

“Villages and woods,” said Santos-Dumont describing his first ascent, “meadows and châteaux, pass across the moving scene, out of which the whistling of locomotives throws sharp notes. These faint, piercing sounds, together with the yelping and barking of dogs, being the only noises that reach one through the depths of the upper air. The human voice cannot mount up into these boundless solitudes. Human beings look like ants along the white lines that are highways, and the rows of houses look like children’s playthings.” From down below a peal of bells sounded, the noonday Angelus ringing from an unknown village belfry. “I had brought up with us a substantial lunch of hard-boiled eggs, cold roast beef and chicken, cheese, ice cream, fruits and cakes, Champagne, coffee and Chartreuse,” Santos-Dumont said. “Nothing is more delicious than lunching like this above the clouds in a spherical balloon. No dining room can be so marvelous in its decoration. The sun sets the clouds in ebullition, making them throw up rainbow jets of frozen vapor like great sheaves of fireworks all around the table.”

The balloonists entered a fog. “The netting holding us to the balloon is visible only up to a certain height,” Santos-Dumont said. “The balloon itself had completely disappeared, so that we had for the moment the delightful impression of hanging in the void without support—of having lost the last ounce of our weight.”6 After nearly two hours in the air, including fifteen minutes spent snagged on a tree while wind gusts “kept us shaking like a salad-basket,”7 Machuron and his enraptured passenger came to rest on the grounds of the Château de La Ferrière, sixty miles from Paris.

By 1901, however, those days of free ballooning were over for Santos-Dumont, now in the midst of his dirigible obsession. Although the determined aeronaut had nearly come a cropper after his encounter with the Trocadéro Hotel, that very evening he laid out specifications for No. 6. The new airship was twenty-two days in the making, and test flights, with the exception of a mishap or two, proved highly successful. No. 6 was larger and, thanks to an air-cooled engine, more powerful than its predecessors. However, like them, it was elegant, even artistic, in appearance and spare in design, especially compared to the frumpy gasbags and the jumble of thick rigging that distinguished the other airships of the era. “I have always been charmed by simplicity,” Santos-Dumont confessed, “while complications, be they ever so ingenious, repel me.”

It was Santos-Dumont’s earlier modification of a simple, two-cylinder, automobile tricycle motor—weighing just sixty-six pounds, yet producing three and a half horsepower—that allowed him to lay claim to having flown the world’s first airship with true dirigibility. Others may have tried (most notably Henri Giffard’s 1852 attempt with a steam-powered engine), but none were truly successful before Santos-Dumont.

“Dirigibility,” as any nineteenth-century aeronaut would have known, meant the ability to navigate through the air by motive power. This is in contrast to being held captive to the wind, as balloonists had been for over a century, and indeed it did take that long before, on September 20, 1898, Santos-Dumont was able to demonstrate dirigibility with his first dirigible airship, No. 1, to great applause on the beautiful grounds of the new Zoological Garden west of Paris. “Under the combined action of the propeller impulse,” he explained, “of the steering rudder, of the displacement of the guide rope, and of the two sacks of ballast sliding backward and forward as I willed, I had the satisfaction of making my evolutions in every direction—to right and left, and up and down.”

Encouraged by the ease in which he could steer No. 1 through the air, Santos-Dumont allowed his craft to rise to 1,300 feet. Whether he estimated or measured this he did not say, but an altimeter, an instrument sensitive to changes in air pressure (which increases and decreases with altitude), would have told him how high he was flying. “At this height I commanded a view of all the monuments of Paris,” he recounted, “and I continued my evolutions in the direction of the Longchamps race-course.”8 As long as Santos-Dumont retained this altitude, the expanding hydrogen kept the gasbag as tight as a drum, but when it came time to descend, the hydrogen contracted and the bag began to fold up like a jackknife. It had been a mistake to have gone so high, a lesson the novice airship navigator had just learned the hard way. “The descent became a fall,” Santos-Dumont said. “Luckily, I was falling in the neighborhood of the grassy turf of Bagatelle, where some big boys were flying kites.” The Brazilian, who spoke perfect French, cried out to the boys to grab the end of his guide rope and run as fast as they could against the wind. “They were bright young fellows, and they grasped the idea and the rope at the same lucky instant,” he said. “The effect of this help in extremis was immediate and as such as I had hoped. By the maneuver we lessened the velocity of the fall, and so avoided what would otherwise have been a bad shaking up, to say the least.” The small aeronaut thanked the big boys and then packed the deflated No. 1 into his wicker basket. “I finally,” he said, “secured a cab and took the relics back to Paris.”

When Santos-Dumont made his third attempt for the Deutsch Prize a month later, the ballooning season had nearly ended and so he had to make this last chance count. No. 6 was ready and, despite wind speeds on top of the Eiffel Tower measuring fourteen miles per hour, telegrams had been sent out to members of the Scientific Commission requesting their presence at Saint Cloud on October 19 at 2 p.m.

The official start came forty-two minutes later and, with a southwest wind striking his craft sideways, Santos-Dumont held an ascending course straight toward his dangerous goal. He reached the tower in record time, but it would not be smooth sailing from then on. “The return trip,” he complained, “was almost directly in the teeth of the wind.”9 After battling the elements for one-third of a mile homeward, his engine threatened to quit, providing “a moment of great uncertainty.” He realized that he had to make a quick decision, and to make it fast. “It was to abandon the steering wheel for a moment, at the risk of drifting from my course, in order to devote my attention to the carbureting lever and the lever controlling the electric spark.”

At the sound of a spluttering engine coming from somewhere above, crowds at the Auteuil racetrack, where the Prix Fin-Picard had just finished, averted their eyes from the horses on the ground. When the cause of the noise was located it provided a splendid sight: that of Santos-Dumont passing perhaps two to three hundred feet overhead with the nose of No. 6 pointing diagonally upward. Although the applauding throng did not know it, the aeronaut was desperately fighting for altitude when, suddenly, his engine came back to life. Spitting thunder, No. 6 shot upward to shouts of alarm below, but Santos-Dumont knew what he was doing and remained composed. “In the air I have no time to fear,” he said, “I have always kept a cool head. Alone in the airship, I was always very busy.”10 The airship commander maintained a firm grip on the rudder while letting his craft climb on its own accord before coaxing it back down to a horizontal position. Then, at an altitude of almost 500 feet and with the propeller spinning madly, No. 6 soared above Longchamps, crossed the Seine, and cont...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index