- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

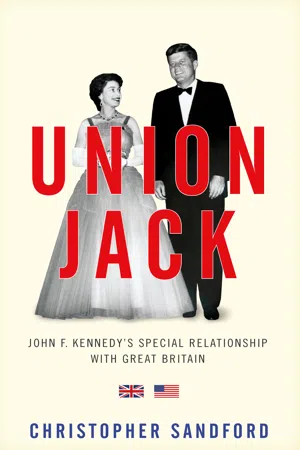

John F. Kennedy carried on a lifelong love affair with England and the English. From his speaking style to his tastes in art, architecture, theater, music, and clothes, his personality reflected his deep affinity for a certain kind of idealized Englishness. In Union Jack, noted biographer Christopher Sandford tracks Kennedy's exploits in Great Britain between 1935 and 1963, and looks in-depth at the unique way Britain shaped JFK throughout his adult life and how JFK charmed British society. This mutual affinity took place against a backdrop of some of the twentieth century's most profound events: The Great Depression, Britain's appeasement of Hitler, the Second World War, the reconstruction of Western Europe, the development and rapid proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and the ideological schism between East and West. Based on extensive archival work as well as firsthand accounts from former British acquaintances, including old girlfriends, Union Jack charts two paths in the life of JFK. The first is his deliberate, long-term struggle to escape the shadow of his father, Joseph Kennedy, former U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain. The second is the emergence of a peculiarly American personality whose consistently pro-British, rallying rhetoric was rivaled only by Winston Churchill. By explaining JFK's special relationship with Great Britain, Union Jack offers a unique and enduring portrait of another side of this historic figure in the centennial year of his birth.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Union Jack by Christopher Sandford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Process. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

“Father Does Not Always Know Best”

FOR THE PAST SIXTY YEARS, the British have occupied a subsidiary role in the much-vaunted Atlantic partnership. In fact, the basic terms of trade were already at work in the last days of World War II, when, over its ally’s strong military objections, the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt unilaterally laid down the strategy for the final conquest of Nazi Germany, although it would be more than a decade before the Anglo-American balance of power assumed its modern tone. It took the Suez crisis of October 1956 to fully execute the mid-twentieth century role reversal that would see London essentially act as a branch office of its Washington headquarters. The story of how Britain, in league with France and Israel, took armed action against the Egyptian dictator Colonel Gamal Nasser following his nationalization of the Suez Canal Company, and how President Eisenhower’s anger at his allies’ intervention was sufficient for Prime Minister Eden, in Downing Street, to recall picking up the transatlantic phone and hearing a flow of soldierly language at the other end “so furious I had to hold the instrument away from my ear” illustrates the harsh truth that national self-interest will usually, if not always, triumph over a fuzzy concept such as the so-called Special Relationship.*

Similarly, in 1965 differing views on Vietnam led Lyndon Johnson to assess the British premier Harold Wilson as “a creep,” while Richard Nixon in turn privately considered Edward Heath “weak” and “as crooked as a corkscrew,” which was surely high praise coming from that quarter. Nor did the British relinquish this peripheral role when Ronald Reagan found himself in power at the same time as Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s, frequently ruffling her feathers on issues ranging from the Strategic Defense Initiative to the US invasion of Grenada. In more recent years, we’ve seen Tony Blair pandering to George W. Bush and Gordon Brown agonizing over the most “culturally correct” gift to take Barack Obama and receiving some hastily acquired DVDs (in a format incompatible with British technology) in return. This has been roughly the state of affairs in the Atlantic alliance right up to the time of President Trump and Prime Minister May in 2017.

The one significant exception to the rule of postwar Anglo-American relations is the presidency of John F. Kennedy. It’s true that there were moments of mutual exasperation in Kennedy’s dealings with his British counterpart Harold Macmillan, both on a personal and a strategic level. Although the specific details are in some doubt, it’s agreed that the libidinous young president once turned to the monogamous, if not celibate, prime minister (born under the reign of Queen Victoria) at the end of a long meeting called to discuss the deployment of nuclear arms and mildly enquired, “I wonder how it is with you, Harold? If I don’t have a woman for three days, I get a terrible headache.”1

Then there was the occasion, in August 1962, when Macmillan returned from an afternoon’s grouse shoot on the Yorkshire moors to find a telegram awaiting him to casually announce that Washington was about to supply a consignment of Hawk surface-to-air missiles to Israel, so preempting a possible sale of Britain’s own Bloodhound rocket. Macmillan’s immediately cabled salvo to Kennedy was not notable for its deference or restraint. There was no salutation. “I have just received the information [about the missiles],” it began, “and that the decision will be conveyed to the Israelis tomorrow. This follows two years of close co-operation during which we decided [the sale] would be unwise.” After some more in this vein, Macmillan went on to get personal. “I cannot believe,” he fumed, “that you were privy to this disgraceful piece of trickery. For myself I must say frankly that I can hardly find words to express my sense of disgust and despair. Nor do I see how you and I are to conduct the great affairs of the world on this basis.”

Four months later, the same two leaders went on to have a contentious meeting at Nassau on the question of Britain’s continued right to possess an independent nuclear deterrent. Following the discussions, the president archly remarked that “looking at it from the [British] point of view—which they do almost better than anybody—it might well be concluded” that they were entitled to such a weapon.2 One of Kennedy’s final acts in office was to commission a report on the whole affair, which he read over the weekend of November 16–17, 1963, as he prepared to leave for campaign trips in Florida and Texas. The First Lady recalled him saying ruefully of the task, “If you want to know what my life is like, read this.” It was the only government paper he ever gave her. An annotated copy of the report—mischievously suggesting it might be sent on as a Christmas gift to Macmillan—was found on top of the files in Kennedy’s briefcase following his assassination.

But on the whole, John Kennedy’s story is remarkable for the distance that he put between his views and those that forged his father Joseph’s notorious World War II isolationism (if not his clinical Anglophobia) and the way in which, with variations of technique and tempo, the young, Democratic president came to share a common purpose and vision of the world with his seemingly decrepit, Conservative British counterpart. Of course, there were compelling tactical reasons for the exceptional closeness of the Atlantic alliance in the years 1961–1963. This was the era of the Berlin Wall and the Cuban Missile Crisis, among several other Soviet-inspired threats to global peace and security. But there are almost always human factors behind political relationships. Kennedy and Macmillan liked each other, in general admired each other, shared a mutual connection to the superbly aristocratic Cavendish family and their ancestral home, and each of them was prepared up to a point to bend his nation’s policy to accommodate the other’s needs—for example, in Kennedy’s guaranteeing the continued British nuclear arsenal over the objections of most of his cabinet and senior advisers at the Nassau summit in December 1962, which was, as one American observer said, “a case of ‘king to king,’ [which] infuriated the court.”3

Kennedy was surely unique among American presidents not only in the depth of his personal prior experience of Britain and Western Europe, but in the almost Shakespearian struggle he waged for some twenty-five years in order to distance his Atlantic policy from that of his still living father. Joseph Kennedy, at least in his tenure as US ambassador to Britain, did not always make a sympathetic figure. He was authoritarian and brusque both with British officials and his own staff (one of whom was found to be a pro-Nazi spy), and while becoming increasingly isolationist and defeatist about Britain’s prospects in the war with Germany, he showed little concern for the sensibilities of the host government once hostilities were declared and even less for the feelings of the British people as they came under a rain of enemy bombs. While still serving as his nation’s representative, Joe argued strongly against giving military or economic aid to the United Kingdom. “Democracy is finished in England. It may be here,” he notoriously stated in an American newspaper interview in November 1940.4

At the time ambassador Kennedy made these remarks, ordinary British citizens were being killed on a nightly basis in German incendiary bombing raids. Just forty-eight hours later, the English midlands city of Coventry was subjected to a sustained terror assault by 515 enemy aircraft, with the loss of an estimated 650 civilian lives and 5,300 buildings, including the town’s medieval cathedral. His comments, consequently, were not well received by the British public as a whole. Kennedy in fact contrived to spend much of his time while in office on home leave in the United States, including a four-month sabbatical in the critical period from November 1939 to March 1940, and even when compelled to remain in England he increasingly preferred to inhabit a seventy-room mansion (today the home of the Legoland theme park) in the western countryside around Windsor rather than to risk personal harm in London.5 As one unattributable but popular quote of the day had it, “I thought my daffodils were yellow until I met Joe Kennedy.”

It has to be said that as ambassador, Kennedy also exhibited a consistently poor sense of timing and protocol. In September 1940, he was once unavoidably close to the scene of a Nazi bombing raid, and his essential contempt for the British people was seen in the offhand remark he made at the time to an embassy colleague named Harvey Klemmer. “The first night of the blitz,” Klemmer recalled, “we walked down Piccadilly and he [Kennedy] said I’d bet you five to one any sum that Hitler will be in Buckingham Palace in two weeks.”6 According to the ambassador’s generally forgiving biographer David Nasaw, it reached the point where “the British Foreign Office began to monitor [Kennedy’s] activities as if he were an enemy agent. . . . They were so concerned by his endless badmouthing of British war efforts that they debated whether to notify [the United Kingdom ambassador] Lord Lothian in Washington and, if necessary, ask him to speak to Mr. Roosevelt.”7

It may well be, as has been argued, that Joe Kennedy’s attitudes to Britain in her hour of peril were founded less on the principle of American isolationism per se than on the fear of a worldwide economic collapse in the event of a prolonged war. In late July 1939, as Hitler planned the further realization of his dream of Lebensraum—the occupation of Poland—Kennedy in turn arranged to take an extended family vacation on the French Riviera. “I am leaving tomorrow on a holiday,” he wired President Roosevelt, “and before I go, I would like to tell you about what I regard as the makings of the worst market conditions the world has ever seen. . . . I feel more pessimistic [about] this than ever.”8

Kennedy’s despondency would seem to have been moved by considerations of racial theory as much as pure economics. “I get very disturbed reading what’s taking place in America on the Jewish question,”9 he wrote in November 1938, voicing his concern that a concerted “Hebrew lobby” would conspire to force the United States into a war with Germany. The following year, Kennedy was agitating, possibly on what he considered humanitarian grounds, for the widespread resettlement of European Jews in remote parts of Venezuela, Costa Rica, and Haiti. More than a decade later, he still seemed bemused at the negative reaction to many of his prewar policies and initiatives, blaming it in part on “a number of Jewish publishers and writers” who had somehow wanted to provoke a fight with Hitler.10

AS THIS BOOK hopefully shows, John F. Kennedy made a long, arduous, but ultimately successful journey to free himself from the taint of his father’s attitudes and prejudices as seen in the critical years leading up to World War II. Although he took longer to outgrow some of those beliefs than others, the younger man came of political age with astonishing speed. Barely two decades after his father’s inglorious departure from London, Kennedy was elected president—an office to which he brought an obvious and profound sympathy for the British position on almost every substantive issue. (Even then, the seventy-two-year-old former ambassador retained his sense of presumed authority, briskly informing his son, the president-elect, that he should nominate his younger brother Bobby to be attorney general, for example.) It remains to be fully seen how much of Jack Kennedy’s path to power was the result of conscious opposition to his father and how much was simply a brilliantly shrewd reaction to changing events and circumstances. In either case, it’s also worth noting that there was a part of America’s thirty-fifth president, whether innate or acquired, that was “more English than the English.”

Time and again in the Kennedy-Macmillan partnership, it was the “cocky young Yank” (as a Foreign Office minister once called him) who proved to be the cool and phlegmatic one and the avuncular Briton who often worked himself up into a nervous state to an extent that made him physically ill before delivering a major speech. In July 1963, on hearing the news of a successful outcome to nuclear test-ban negotiations in Moscow, Macmillan, having waited anxiously by his phone all day, promptly burst into tears of relief. Kennedy’s own published schedule for the day in question notes only some routine meetings with cabinet officers and visiting Ethiopian dignitaries, although it’s thought he may have allowed himself a celebratory cigar following his mid-afternoon swim. Similarly, Kennedy loved British historical literature and political gossip; although afflicted by a whole series of truly debilitating illnesses, he apparently thought it bad form to speak of such things in public; and as his close British friend David Ormsby-Gore, son of Lord Harlech, remarked, “He was somebody who didn’t like the display of undue emotions. . . . His character told him that people who become hysterical and get overexcited don’t usually have good judgment—it’s not actually an emotion for which he had any great admiration.”11 In short, Kennedy—the embodiment of the American New Frontier—was in some ways more stereotypically an Englishman.

In London, Joe Kennedy’s popularity had reached the lowest point of its curve with his notorious “Democracy is finished” outburst in 1940. “While he was here his suave monotonous smile, his nine over-photographed children and his hail-fellow-well-met manner concealed a hard-boiled business man’s eagerness to do a profitable deal with the dictators and deceive many English people,” A. J. Cummings wrote in the London News Chronicle.12 It wasn’t just that the soon-to-depart ambassador had appeared to betray the trust of his nation’s closest ally. His perfidy also seemed to undermine the political prospects of his two oldest sons, Joe Jr. and Jack, both of them frequently resident at the embassy in London and each, in his own way, with ambitions of future public service. It was a case of “the old name be[ing] mud in England for the next generation,” Jack noted ruefully to a local friend.13 The twenty-three-year-old was even sufficiently moved to write to his father in December 1940 to complain that he found himself being personally attacked in the British press as “being an appeaser and a defeatist.” That sort of reputation could prove ruinous to Kennedys both young and old, he went on to warn. “It must be remembered continually that you wish to shake off the word ‘appeaser,’” Jack told his father. “It seems to me that if this label is tied to you it may nullify your immediate effectiveness, even though in the long run you may be proved correct.”14 “We regarded the [former] ambassador with some contempt,” Harold Macmillan confirmed following the American presidential election of 1960. “It was generally thought he was unfriendly, and defeatist. . . . I had no particular reason to have any affection for his son.”15

In all, then, John Kennedy’s legacy from his father was mixed: he enjoyed certain contacts and points of access in the higher echelons of British society not normally open to a young American undergraduate. But set against this, he was tarred with the same brush as the ex-ambassador—“Jittery Joe”—whom many in England saw not only as a self-centered and crooked “twister,” but also as positively ludicrous in some of his social affectations. Longing to be accepted as a shrewd and progressive businessman, Joe was at the same time touchingly gratified to...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1 } “Father Does Not Always Know Best”

- 2 } My Trip Abroad

- 3 } Why England Slept

- 4 } A Very Broad-Minded Approach to Everything

- 5 } Europe’s New Order

- 6 } John F. Kennedy Slept Here

- 7 } Family Feud

- 8 } Special Relationships

- 9 } “We Are Attempting to Prevent World War Three”

- 10 } Harold and Jack

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- Illustrations