- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

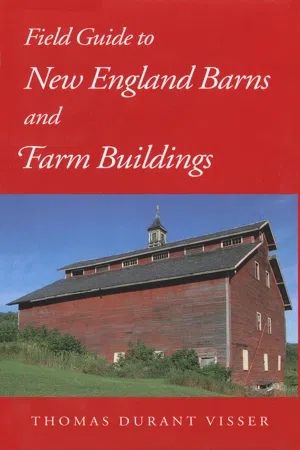

Field Guide to New England Barns and Farm Buildings

About this book

The quintessential New England barn–photogenic, full of character, and framed by flaming autumn foliage–is an endangered species. Of some 30,000 barns in Vermont alone, nearly a thousand a year are lost to fire, collapse, or bulldozers. Thomas Durant Visser's field guide to the barns, silos, sugar houses, granaries, tobacco barns, and potato houses of New England is an attempt to document not just their structure but their traditions and innovations before the surviving architectural evidence of this rich rural heritage is lost forever. A recognized authority on historic barn preservation, Visser has combed the six-state region for representative barns and outbuildings, and 200 of his photographs are reproduced here. The text, which includes accounts from 18th– and 19th–century observers, describes key architectural characteristics, historic uses, and geographic distribution as well as specific features like timbers and frames, sheathings, doors, and cupolas. From English barns to bank barns, from ice houses to outhouses, these irreplaceable assets, Visser writes, "linger as vulnerable survivors of the past. Yet before these buildings vanish, each has a story to tell." Travelers, residents, and scholars alike will find Visser's text invaluable in uncovering, understanding, and appreciating the stories inherent in these dwindling cultural artifacts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Field Guide to New England Barns and Farm Buildings by Thomas Durant Visser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Discovering the History of Farm Buildings

Fig. 1-1. Dairy farm with mid-nineteenth-century barns in Franklin County, Vermont.

The architectural legacy of New England’s rich agricultural heritage awaits discovery across much of the region’s landscape. Whether surrounded by hay fields or scattered through developed residential areas, historic barns and farm buildings linger as vulnerable survivors of the past. Yet before these buildings vanish, each has a story to tell. Together they provide a fascinating window into the cultural traditions and technological innovations that helped shape the history and landscape of New England.

Since written information about the history of specific farm structures is usually scarce, the best source of historical evidence is often the building itself. This chapter discusses some ways to estimate the age of a building through a careful examination of its construction materials, frame design, and architectural features. By correlating such bits of evidence with an understanding of the evolution of building technology and farming practices, it is often possible to piece together the history of a barn. Reading the history of a structure from physical evidence can be challenging. Often one must play the role of a detective to decipher clues of the past through observations of intermingled layers of evidence and alterations.

Usually, the design and types of materials used in a building indicate the age of construction, but New Englanders often used salvaged boards and old timbers when rebuilding their barns. Although unraveling this contradictory evidence can pose a challenge to researchers, a careful examination of the recycled materials may reveal the type and size of the building that was torn down. Thus, a large barn built in the late nineteenth century might have hand-hewn beams from a farm’s original late-eighteenth-century barn. Wear patterns on floor boards, empty mortises in timbers, and “ghost lines” on walls may reveal missing interior features. A bright flashlight and a camera with a flash are valuable tools for barn research. A careful walk around the farmstead may even reveal stones marking the footprint of the earlier barn.

Fig. 1-2. Circa 1790 English barn, Westford, Vermont. Around 1900 this barn was moved onto a new foundation, with cow stables in the basement. The original main door opening was located in the middle of the side wall between the posts behind the barrel.

From the outside the most effective identification procedure for vernacular farm buildings is to first determine their function, based on the size, shape, location, and distinctive exterior features. Examples of the major types of historic New England farm buildings are illustrated in this field guide.

Design Traditions, Fashions, and Innovations

Before exploring the evolution of farm building design in New England, perhaps we should ask: Who decides how a structure is designed and built? What factors influence these decisions?

Certainly, the answers are complex. The intended uses of the building, the siting options, the availability of materials, and the budget all influence design decisions by the owner. In addition, the farmer could be influenced by suggestions from family members and friends, designs completed by neighboring farmers, and perhaps recommendations offered in agricultural newspapers and other publications.

Although some New England farmers had the time, talent, tools, and experience to work professionally as carpenters or builders, for most farmers construction work was limited by their busy schedules. Winter often allowed time for logging and for hewing timbers, but only a few weeks in the early summer, between the planting season and the haying season, were available to launch major construction projects. For these, farm owners typically employed a contractor or master builder to oversee the project and design the timber frame and carpentry details.

Preparations for building a large barn could take years of saving and collecting materials. Some farmers harvested their own trees for the boards and timbers that were sawn or hewn to the dimensions specified by the master builder. After helping to plan the building with the owner, often months or years in advance, the master builder would arrive with a skilled framing crew. Within several weeks the timbers would be cut and the frame erected. Barn raisings were occasionally large social events, with scores of neighbors and friends available to lend a hand (see fig. 1-22). Most small farm buildings, however, were probably swiftly erected with the deliberate work of less than a half dozen workers. The owner would typically hire other tradesmen to prepare the foundation and do the finish carpentry. Farmhands and family members often helped with site work, raising the frame, laying floors, and boarding and shingling the building.1

The role and influence of skilled master builders, timber framers, and carpenters in the design of vernacular architecture is often ignored. The occupations typically required a period of training through a lengthy apprenticeship. As early as the seventeenth-century colonial English settlement of New England, these specialized tradesmen were among those actively recruited for voyages to the New World.2

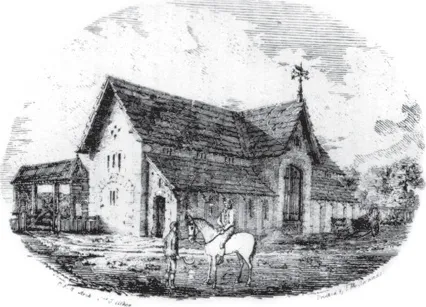

By comparing the architectural features of farm buildings in old England and New England, we can see that early colonial farmers and their barn builders generally followed the traditional English building designs that were common to their original home regions, with innovations made for the harsher climate and availability of construction materials. Some features of early New England farm architecture can be traced back to the Elizabethan and medieval eras. An example is the basic design of the barn. Following a plan used from the Middle Ages for the storage and processing of grain harvests, the interior of the old English barn was typically divided into three sections with large storage bays on both gable ends. Separating the bays was a central wooden threshing floor aligned with pairs of hinged doors on the front and rear eaves sides. This design would allow farmers to bring wagons into the barn to unload the grain or hay and then drive forward to exit.

Fig. 1-3. As this 1830s architect’s rendering of a picturesque “Old English Barn” suggests, barns built in Elizabethan England often featured gable-roofed “porches” to shelter the side entrances.

Early New England farmers modified the old English barn design by combining the functions of both the English grain barn and the cow stable into one larger building. Known simply as “the barn,” the practicality of the design is reflected by its lack of change for nearly two centuries.

The so-called English barn design built in New England before the early nineteenth century balanced the functional and structural needs of the building with an aesthetic that echoes a medieval English heritage. Each piece of the barn frame was handcrafted for its specific location and function. Squat posts and oversize beams supporting thin, tapered rafters and purlins express a hierarchy of proportion. Smooth surfaces of adzed timbers contrast with the raw, natural textures of unfinished log floor joists.

Rather than introducing overtly stylish embellishments intended for the pleasure of humans into a realm shared with domesticated farm animals, the austere design vocabulary for barns traditionally reflects the practical purposes of protecting harvests, sheltering work, and comforting the herds and flocks. But through this austerity we may also detect an elegance of grace and simplicity.

With the deeply engrained Puritan ethic of frugality and hard work etched into the New England culture, decorations on farm buildings were few. Indeed, before the mid-1800s decorative embellishments on New England barns might be limited to a few patterned holes cut high in the gable walls, but even these served the practical purpose of housing swallows and other birds. As one Groton, Connecticut, farmer reminisced in 1855:

In barns built after the old style, “swallow holes” were always to be seen. In some of these barns I have counted twenty nests at one time, all of them being occupied. A barn swarming with a multitude of such happy, innocent inhabitants, resounds with such flutterings, twitterings and gushing outbursts of song, that it seems as if every one who enters within its precincts, even if he be a confirmed hypochondriac, must forget all his troubles, and feel his heart drawn upwards to praise Him “to whom praise alone praise is due,” for their cheerful melodies. . . . And, besides the pleasure we receive from their society, they, and especially the swallows, destroy during their short stay with us an innumerable multitude of insects, which is a fact of no little importance in these insectivorous times.3

Most New England farmers were content with traditional austere designs for their barns (as well as their houses) through the first half of the nineteenth century, but fashions were changing. The profound influences of the industrial revolution were ushering in an era of experimentation and innovation influenced by new construction technologies, advances in the agricultural sciences, and the “Victorian” design aesthetic th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface to Ebook Edition

- Preface

- 1 Discovering the History of Farm Buildings

- 2 Barns

- 3 Outbuildings

- 4 Buildings for Feed Storage

- 5 Other Farm Buildings

- 6 Farm Buildings for Specialty Crops

- Notes

- Index