eBook - ePub

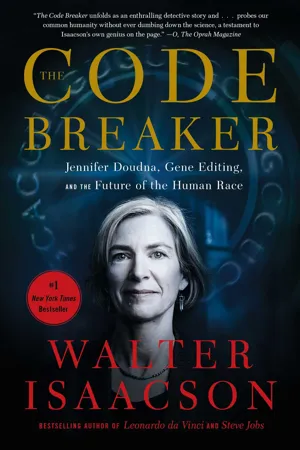

The Code Breaker

Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race

- 560 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A Best Book of 2021 by Bloomberg BusinessWeek, Time, and The Washington Post

The bestselling author of Leonardo da Vinci and Steve Jobs returns with a “compelling” (The Washington Post) account of how Nobel Prize winner Jennifer Doudna and her colleagues launched a revolution that will allow us to cure diseases, fend off viruses, and have healthier babies.

When Jennifer Doudna was in sixth grade, she came home one day to find that her dad had left a paperback titled The Double Helix on her bed. She put it aside, thinking it was one of those detective tales she loved. When she read it on a rainy Saturday, she discovered she was right, in a way. As she sped through the pages, she became enthralled by the intense drama behind the competition to discover the code of life. Even though her high school counselor told her girls didn’t become scientists, she decided she would.

Driven by a passion to understand how nature works and to turn discoveries into inventions, she would help to make what the book’s author, James Watson, told her was the most important biological advance since his codiscovery of the structure of DNA. She and her collaborators turned a curiosity of nature into an invention that will transform the human race: an easy-to-use tool that can edit DNA. Known as CRISPR, it opened a brave new world of medical miracles and moral questions.

The development of CRISPR and the race to create vaccines for coronavirus will hasten our transition to the next great innovation revolution. The past half-century has been a digital age, based on the microchip, computer, and internet. Now we are entering a life-science revolution. Children who study digital coding will be joined by those who study genetic code.

Should we use our new evolution-hacking powers to make us less susceptible to viruses? What a wonderful boon that would be! And what about preventing depression? Hmmm…Should we allow parents, if they can afford it, to enhance the height or muscles or IQ of their kids?

After helping to discover CRISPR, Doudna became a leader in wrestling with these moral issues and, with her collaborator Emmanuelle Charpentier, won the Nobel Prize in 2020. Her story is an “enthralling detective story” (Oprah Daily) that involves the most profound wonders of nature, from the origins of life to the future of our species.

The bestselling author of Leonardo da Vinci and Steve Jobs returns with a “compelling” (The Washington Post) account of how Nobel Prize winner Jennifer Doudna and her colleagues launched a revolution that will allow us to cure diseases, fend off viruses, and have healthier babies.

When Jennifer Doudna was in sixth grade, she came home one day to find that her dad had left a paperback titled The Double Helix on her bed. She put it aside, thinking it was one of those detective tales she loved. When she read it on a rainy Saturday, she discovered she was right, in a way. As she sped through the pages, she became enthralled by the intense drama behind the competition to discover the code of life. Even though her high school counselor told her girls didn’t become scientists, she decided she would.

Driven by a passion to understand how nature works and to turn discoveries into inventions, she would help to make what the book’s author, James Watson, told her was the most important biological advance since his codiscovery of the structure of DNA. She and her collaborators turned a curiosity of nature into an invention that will transform the human race: an easy-to-use tool that can edit DNA. Known as CRISPR, it opened a brave new world of medical miracles and moral questions.

The development of CRISPR and the race to create vaccines for coronavirus will hasten our transition to the next great innovation revolution. The past half-century has been a digital age, based on the microchip, computer, and internet. Now we are entering a life-science revolution. Children who study digital coding will be joined by those who study genetic code.

Should we use our new evolution-hacking powers to make us less susceptible to viruses? What a wonderful boon that would be! And what about preventing depression? Hmmm…Should we allow parents, if they can afford it, to enhance the height or muscles or IQ of their kids?

After helping to discover CRISPR, Doudna became a leader in wrestling with these moral issues and, with her collaborator Emmanuelle Charpentier, won the Nobel Prize in 2020. Her story is an “enthralling detective story” (Oprah Daily) that involves the most profound wonders of nature, from the origins of life to the future of our species.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Code Breaker by Walter Isaacson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Tecnología e ingeniería & Biografías de ciencias sociales. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE The Origins of Life

The Lord God made a garden in the east, in Eden;and there he put the man he had made.Out of the ground the Lord God caused to growevery tree that is beautiful and good for food;the tree of life also in the midst of the garden,and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.—Genesis 2:8–9

CHAPTER 1 Hilo

Haole

Had she grown up in any other part of America, Jennifer Doudna might have felt like a regular kid. But in Hilo, an old town in a volcano-studded region of the Big Island of Hawaii, the fact that she was blond, blue-eyed, and lanky made her feel, she later said, “like I was a complete freak.” She was teased by the other kids, especially the boys, because unlike them she had hair on her arms. They called her a “haole,” a term that, though not quite as bad as it sounds, was often used as a pejorative for non-natives. It imbedded in her a slight crust of wariness just below the surface of what would later become a genial and charming demeanor.1

A tale that became part of the family lore involved one of Jennifer’s great-grandmothers. She was part of a family of three brothers and three sisters. Their parents could not afford for all six to go to school, so they decided to send the three girls. One became a teacher in Montana and kept a diary that has been handed down over the generations. It is filled with tales of perseverance, broken bones, working in the family store, and other frontier endeavors. “She was crusty and stubborn and had a pioneering spirit,” said Jennifer’s sister Sarah, the current generation’s keeper of the diary.

Jennifer was likewise one of three sisters, but there were no brothers. As the oldest, she was doted on by her father, Martin Doudna, who sometimes referred to his children as “Jennifer and the girls.” She was born February 19, 1964, in Washington, D.C., where her father worked as a speechwriter for the Department of Defense. He yearned to be a professor of American literature, so he moved to Ann Arbor with his wife, a community college teacher named Dorothy, and enrolled at the University of Michigan.

When he earned his doctorate, he applied for fifty jobs and got only one offer, from the University of Hawaii at Hilo. So he borrowed $900 from his wife’s retirement fund and moved his family there in August 1971, when Jennifer was seven.

Many creative people—including most of those I have chronicled, such as Leonardo da Vinci, Albert Einstein, Henry Kissinger, and Steve Jobs—grew up feeling alienated from their surroundings. That was the case for Doudna as a young blond girl among the Polynesians in Hilo. “I was really, really alone and isolated at school,” she says. In the third grade, she felt so ostracized that she had trouble eating. “I had all sorts of digestive problems that I later realized were stress related. Kids would tease me every day.” She retreated into books and developed a defensive layer. “There’s an internal part of me they’ll never touch,” she told herself.

Like many others who have felt like an outsider, she developed a wide-ranging curiosity about how we humans fit into creation. “My formative experience was trying to figure out who I was in the world and how to fit in in some way,” she later said.2

Fortunately, this sense of alienation did not become too ingrained. Life as a schoolkid got better, she developed a genial spirit, and the scar tissue of early childhood began to fade. It would become inflamed only on rare occasions, when some act—an end run on a patent application, a male business colleague being secretive or misleading—scratched deeply enough.

Blossoming

The improvement began halfway through third grade, when her family moved from the heart of Hilo to a new development of cookie-cutter houses that had been carved into a forested slope further up the flanks of the Mauna Loa volcano. She switched from a large school, with sixty kids per grade, to a smaller one with only twenty. They were studying U.S. history, a subject that made her feel more connected. “It was a turning point,” she recalled. She thrived so well that by the time she was in fifth grade, her math and science teacher urged that she skip ahead. So her parents moved her into sixth grade.

That year she finally made a close friend, one she kept throughout her life. Lisa Hinkley (now Lisa Twigg-Smith) was from a classic mixed-race Hawaiian family: part Scottish, Danish, Chinese, and Polynesian. She knew how to handle the bullies. “When someone would call me a f—king haole, I would cringe,” Doudna recalled. “But when a bully called Lisa names, she would turn and look right at him and give it right back to him. I decided I wanted to be that way.” One day in class the students were asked what they wanted to be when they grew up. Lisa proclaimed that she wanted to be a skydiver. “I thought, ‘That is so cool.’ I couldn’t imagine answering that. She was very bold in a way that I wasn’t, and I decided to try to be bold as well.”

Doudna and Hinkley spent their afternoons riding bikes and hiking through sugarcane fields. The biology was lush and diverse: moss and mushrooms, peach and arenga palms. They found meadows filled with lava rocks covered in ferns. In the lava-flow caves there lived a species of spider with no eyes. How, Doudna wondered, did it come to be? She was also intrigued by a thorny vine called hilahila or “sleeping grass” because its fernlike leaves curl up when touched. “I asked myself,” she recalls, “ ‘What causes the leaves to close when you touch them?’ ”3

We all see nature’s wonders every day, whether it be a plant that moves or a sunset that reaches with pink fingers into a sky of deep blue. The key to true curiosity is pausing to ponder the causes. What makes a sky blue or a sunset pink or a leaf of sleeping grass curl?

Doudna soon found someone who could help answer such questions. Her parents were friends with a biology professor named Don Hemmes, and they would all go on nature walks together. “We took excursions to Waipio Valley and other sites on the Big Island to look for mushrooms, which was my scientific interest,” Hemmes recalls. After photographing the fungi, he would pull out his reference books and show Doudna how to identify them. He also collected microscopic shells from the beach, and he would work with her to categorize them so they could try to figure out how they evolved.

Her father bought her a horse, a chestnut gelding named Mokihana, after a Hawaiian tree with a fragrant fruit. She joined the soccer team, playing halfback, a position that was hard to fill on her team because it required a runner with long legs and lots of stamina. “That’s a good analogy to how I’ve approached my work,” she said. “I’ve looked for opportunities where I can fill a niche where there aren’t too many other people with the same skill sets.”

Math was her favorite class because working through proofs reminded her of detective work. She also had a happy and passionate high school biology teacher, Marlene Hapai, who was wonderful at communicating the joy of discovery. “She taught us that science was about a process of figuring things out,” Doudna says.

Although she began doing well academically, she did not feel that there were high expectations in her small school. “I didn’t get the sense that the teachers really expected very much of me,” she said. She had an interesting immune response: the lack of challenges made her feel free to take more chances. “I decided you just have to go for it, because what the hell,” she recalled. “It made me more willing to take on risks, which is something I later did in science when I chose projects to pursue.”

Her father was the one person who pushed her. He saw his oldest daughter as his kindred spirit in the family, the intellectual who was bound for college and an academic career. “I always felt like I was the son that he wanted to have,” she says. “I was treated a bit differently than my sisters.”

James Watson’s The Double Helix

Doudna’s father was a voracious reader who would check out a stack of books from the local library each Saturday and finish them by the following weekend. His favorite writers were Emerson and Thoreau, but as Jennifer was growing up he became more aware that the books he assigned to his class were mostly by men. So he added Doris Lessing, Anne Tyler, and Joan Didion to his syllabus.

Often he would bring home a book, either from the library or the local secondhand bookstore, for her to read. And that is how a used paperback copy of James Watson’s The Double Helix ended up on her bed one day when she was in sixth grade, waiting for her when she got home from school.

She put the book aside, thinking it was a detective tale. When she finally got around to reading it on a rainy Saturday afternoon, she discovered that she was right, in a sense. As she sped through the pages, she became enthralled with what was an intensely personal detective drama, filled with vividly portrayed characters, about ambition and competition in the pursuit of nature’s inner truths. “When I finished, my father discussed it with me,” she recalls. “He liked the story and especially the very personal side of it—the human side of doing that kind of research.”

In the book, Watson dramatized (and overdramatized) how as a twenty-four-year-old bumptious biology student from the American Midwest he ended up at Cambridge University in England, bonded with the biochemist Francis Crick, and together won the race to discover the structure of DNA in 1953. Written in the sparky narrative style of a brash American who has mastered the English after-dinner art of being self-deprecating and boastful at the same time, the book manages to smuggle a large dollop of science into a gossipy narrative about the foibles of famous professors, along with the pleasures of flirting, tennis, lab experiments, and afternoon tea.

In addition to the role of lucky naïf that he concocted as his own persona in the book, Watson’s other most interesting character is Rosalind Franklin, a structural biologist and crystallographer whose data he used without her permission. Displaying the casual sexism of the 1950s, Watson refers to her condescendingly as “Rosy,” a name she never used, and pokes fun at her severe appearance and chilly personality. Yet he also is generous in his respect for her mastery of the complex science and beautiful art of using X-ray diffraction to discover the structure of molecules.

“I guess I noticed she was treated a bit condescendingly, but what mainly struck me was that a woman could be a great scientist,” Doudna says. “It may sound a bit crazy. I guess I must have heard about Marie Curie. But reading the book was the first time I really thought about it, and it was an eye-opener. Women could be scientists.”4

The book also led Doudna to realize something about nature that was at once both logical and awe-inspiring. There were biological mechanisms that governed living things, including the wondrous phenomena that caught her eye when she hiked through the rainforests. “Growing up in Hawaii, I had always liked hunting with my dad for interesting things in nature, like the ‘sleeping grass’ that curls up when you touch it,” she recalls. “The book made me realize you could also hunt for the reasons why nature worked the way it did.”

Doudna’s career would be shaped by the insight that is at the core of The Double Helix: the shape and structure of a chemical molecule determine what biological role it can play. It is an amazing revelation for those who are interested in uncovering the fundamental secrets of life. It is the way that chemistry—the study of how atoms bond to create molecules—becomes biology.

In a larger sense, her career would also be shaped by the realization that she was right when she first saw The Double Helix on her bed and thought that it was one of those detective mysteries that she loved. “I have always loved mystery stories,” she noted years later. “Maybe that explains my fascination with science, which is humanity’s attempt to understand the longest-running mystery we know: the origin and function of the natural world and our place in it.”5

Even though her school didn’t encourage girls to become scientists, she decided that is what she wanted to do. Driven by a passion to understand how nature works and by a competitive desire to turn discoveries into inventions, she would help make what Watson, with his typical grandiosity cloaked in the pretense of humility, would later tell her was the most important biological advance since the double helix.

Darwin

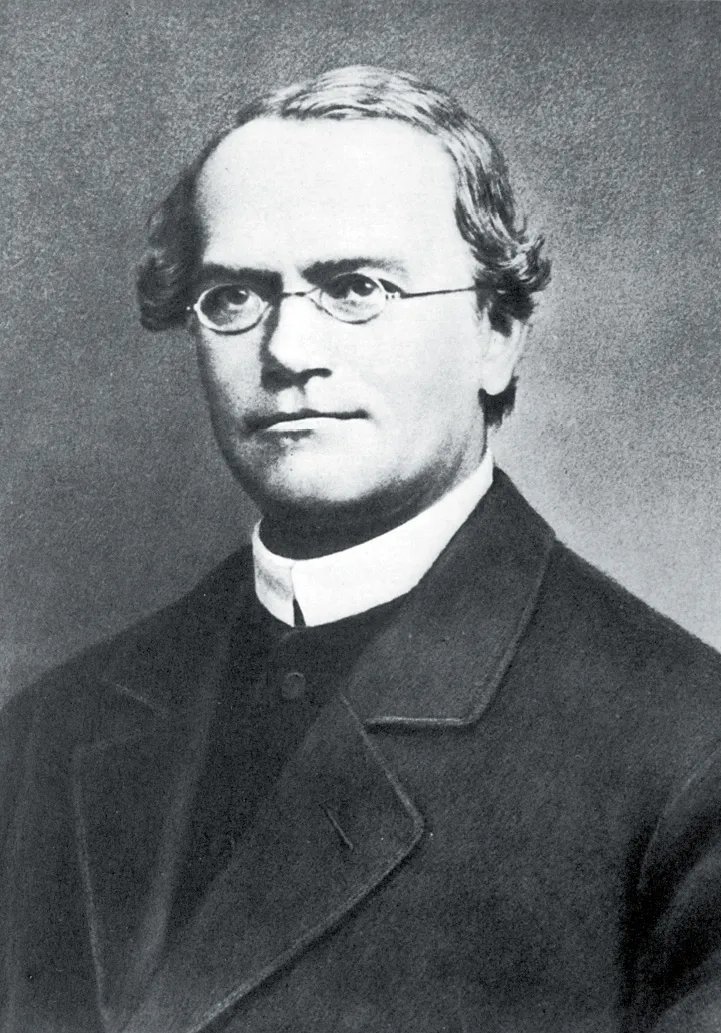

Mendel

CHAPTER 2 The Gene

Darwin

The paths that led Watson and Crick to the discovery of DNA’s structure were pioneered a century earlier, in the 1850s, when the English naturalist Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species and Gregor Mendel, an underemployed priest in Brno (now part of the Czech Republic), began breeding peas in the garden of his abbey. The beaks of Darwin’s finches and the traits of Mendel’s peas gave birth to the idea of the gene, an entity inside of living organisms that carries the code of heredity.1

Darwin had originally planned to follow the career path of his father and grandfather, who were distinguished doctors. But he found himself horrified by the sight of blood and the screams of a strapped-down child undergoing surgery. So he quit medical school and began studying to become an Anglican parson, another calling for which he was uniquely unsuited. His true passion, ever since he began collecting specimens at age eight, was to be a naturalist. He got his opportunity in 1831 when, at age twenty-two, he was offered the chance to ride as the gentleman collector on a round-the-world voyage of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Introduction: Into the Breach

- Part One: The Origins of Life

- Part Two: Crispr

- Part Three: Gene Editing

- Part Four: CRISPR in Action

- Part Six: CRISPR Babies

- Part Seven: The Moral Questions

- Part Eight: Dispatches from the Front

- Part Nine: Coronavirus

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Notes

- Index

- Image Credits

- Copyright