- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

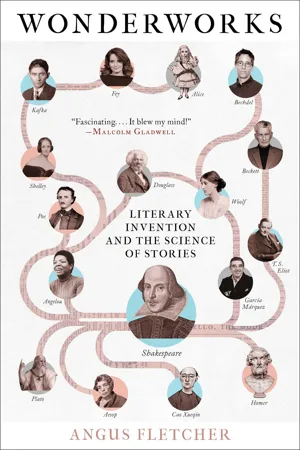

This "fascinating" (Malcolm Gladwell, New York Times bestselling author of Outliers ) examination of literary inventions through the ages, from ancient Mesopotamia to Elena Ferrante, shows how writers have created technical breakthroughs—rivaling scientific inventions—and engineering enhancements to the human heart and mind. Literature is a technology like any other. And the writers we revere—from Homer, Shakespeare, Austen, and others—each made a unique technical breakthrough that can be viewed as both a narrative and neuroscientific advancement. Literature's great invention was to address problems we could not solve: not how to start a fire or build a boat, but how to live and love; how to maintain courage in the face of death; how to account for the fact that we exist at all. Wonderworks reviews the blueprints for twenty-five of the most significant developments in the history of literature. These inventions can be scientifically shown to alleviate grief, trauma, loneliness, anxiety, numbness, depression, pessimism, and ennui, while sparking creativity, courage, love, empathy, hope, joy, and positive change. They can be found throughout literature—from ancient Chinese lyrics to Shakespeare's plays, poetry to nursery rhymes and fairy tales, and crime novels to slave narratives.A "refreshing and remarkable" (Jay Parini, author of Borges and Me: An Encounter ) exploration of the new literary field of story science, Wonderworks teaches you everything you wish you learned in your English class, and "contains many instances of critical insight....What's most interesting about this compendium is its understanding of imaginative representation as a technology" ( The New York Times ).

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

ONE Rally Your Courage

The Origins of the Invention

The tone was the ring and timbre of the voice. Maybe the voice trembled when it spoke of terrible creatures or chuckled when it spoke of ridiculous coincidences. Maybe the voice was rich with empathy when describing the pains of the poor, or deep with wonder when talking of the gods.The taste was the subject matter preferred by the voice. Maybe the voice liked to concentrate on nature and the seasons. Maybe the voice preferred to speak at length about love, or war, or urban architecture, or sea leviathans.

We do not really mean, we do not really mean that what we are about to say is true. A story, a story; let it come, let it go.

When all was water, the animals were above in Galûñ'lăt, beyond the arch; but it was very much crowded, and they were wanting more room. They wondered what was below the water, and at last Dâyuni'sĭ, “Beaver’s Grandchild,” the little Water-beetle, offered to go and see if it could learn. It darted in every direction over the surface of the water, but could find no firm place to rest. Then it dived to the bottom and came up with some soft mud, which began to grow and spread on every side until it became the island which we call the earth. It was afterward fastened to the sky with four cords, but no one remembers who did this.

The Narrator God

- Wonder. Wonder, as we saw in the introduction, is generated by the stretch. And stretch is what the God Voice does. It stretches truth into Truth, and law into Law, and light into cosmic brightness, making all the stuff of life feel bigger, expanded from the familiar to the divine.

- Fear. Fear is a near cousin to wonder; things that inspire awe were once said to be “awe-full” or “awful,” because the same bigness that stretches our brain can easily alarm. So, it’s only to be expected that a narrator who booms like an omnipotent deity would make us nervous. Its gigantic size is scare inducing; it skips our pulse and sends a light chill down our spine.

Courage—and Its Neural Source

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Preface: A Heaven of Invention

- Introduction: The Lost Technology

- Chapter 1: Rally Your Courage: Homer’s Iliad and the Invention of the Almighty Heart

- Chapter 2: Rekindle the Romance: Sappho’s Lyrics, the Odes of Eastern Zhou, and the Invention of the Secret Discloser

- Chapter 3: Exit Anger: The Book of Job, Sophocles’s Oedipus Tyrannus, and the Invention of the Empathy Generator

- Chapter 4: Float Above Hurt: Aesop’s Fables, Plato’s Meno, and the Invention of the Serenity Elevator

- Chapter 5: Excite Your Curiosity: The Epic of Sundiata, the Modern Thriller, and the Invention of the Tale Told from Our Future

- Chapter 6: Free Your Mind: Dante’s Inferno, Machiavelli’s Innovatori, and the Invention of the Vigilance Trigger

- Chapter 7: Jettison Your Pessimism: Giovanni Straparola, the Original Cinderella, and the Invention of the Fairy-tale Twist

- Chapter 8: Heal from Grief: Shakespeare’s Hamlet and the Invention of the Sorrow Resolver

- Chapter 9: Banish Despair: John Donne’s “Songs” and the Invention of the Mind-Eye Opener

- Chapter 10: Achieve Self-Acceptance: Cao Xueqin’s Dream of the Red Chamber, Zhuangzi’s “Tale of Wonton,” and the Invention of the Butterfly Immerser

- Chapter 11: Ward Off Heartbreak: Jane Austen, Henry Fielding, and the Invention of the Valentine Armor

- Chapter 12: Energize Your Life: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Modern Meta-Horror, and the Invention of the Stress Transformer

- Chapter 13: Solve Every Mystery: Francis Bacon, Edgar Allan Poe, and the Invention of the Virtual Scientist

- Chapter 14: Become Your Better Self: Frederick Douglass, Saint Augustine, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and the Invention of the Life Evolver

- Chapter 15: Bounce Back from Failure: George Eliot’s Middlemarch and the Invention of the Gratitude Multiplier

- Chapter 16: Clear Your Head: “Rashōmon,” Julius Caesar, and the Invention of the Second Look

- Chapter 17: Find Peace of Mind: Virginia Woolf, Marcel Proust, James Joyce, and the Invention of the Riverbank of Consciousness

- Chapter 18: Feed Your Creativity: Winnie-the-Pooh, Alice in Wonderland, and the Invention of the Anarchy Rhymer

- Chapter 19: Unlock Salvation: To Kill a Mockingbird, Shakespeare’s Soliloquy Breakthrough, and the Invention of the Humanity Connector

- Chapter 20: Renew Your Future: Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, and the Invention of the Revolution Rediscovery

- Chapter 21: Decide Wiser: Ursula Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, Thomas More’s Utopia, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, and the Invention of the Double Alien

- Chapter 22: Believe in Yourself: Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings and the Invention of the Choose Your Own Accomplice

- Chapter 23: Unfreeze Your Heart: Alison Bechdel, Euripides, Samuel Beckett, T. S. Eliot, and the Invention of the Clinical Joy

- Chapter 24: Live Your Dream: Tina Fey’s 30 Rock, a Dash of “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious,” and the Invention of the Wish Triumphant

- Chapter 25: Lessen Your Lonely: Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, and the Invention of the Childhood Opera

- Conclusion: Inventing Tomorrow

- Coda: The Secret History of This Book

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Translations, Sources, and Further Reading

- About the Author

- Index

- Copyright