Imagine the following scenario –

You wake up on a chilly, dark morning in winter. You have a cold; your head hurts and your nose is blocked. You get up and drag yourself to the shower, but because you aren’t feeling well, getting ready takes longer and you don’t have time for breakfast. You get into university and into your first class of the day, only to discover that your two best friends are also ill and have decided to stay at home. Feeling a little lonely, hungry, ill and cold, you settle down at a desk by yourself. You don’t like the class that is about to begin, and you find the subject boring.

How much learning do you think you’ll do in this class? How easy will it be to concentrate, take in new information, make connections to things you’ve already learned and increase your understanding of this subject?

Now imagine this scenario –

You wake up on a sunny day, late in spring. You slept well the night before and feel refreshed and full of energy. You eat your favourite breakfast and then head into university for your favourite class, on a subject that you’re passionate about. As you wait for class to start, you chat to your two best friends and make plans for fun things you’ll do this weekend.

How much learning will you do in this class? How easy will it be to concentrate, take in new information, make connections to things you’ve already learned and increase your understanding of this subject?

When put like this, it’s easy to say that you will probably learn more in the second scenario. When we’re feeling full of energy and enthusiasm, it is much easier to learn and perform well than when we feel ill, tired, upset, hungry or lonely. When we set these two scenarios together like this, it is easy to see how our wellbeing can impact on our learning and academic performance.

But now let’s ask another question – when you usually think about your learning and academic achievement, how often do you think about the role your wellbeing played in how much you learned or in the grades you got?

For many of the students that I’ve worked with over the years, when they think about what might determine their academic learning and performance, their wellbeing comes way behind other thoughts (if at all). Most students tend to focus on their own academic ability, the quality of the teaching they received, how much work they did, the practical things that got in the way or helped them, and luck.

For those students who do think about the role their wellbeing has played, it’s often because something very obvious happened – they fell ill just before an exam or they experienced severe exam anxiety, for instance.

Other students may be aware that improving their wellbeing might help their learning, but they don’t yet know how to make positive changes that will stick.

The relationship between our wellbeing and our learning can be one of those things we sort of know about but don’t think about or prioritise. As a result, we can slip into behaviours and habits that mean we learn less and, as a result, get less enjoyment out of being a student.

Luckily, there are many ways to improve your wellbeing and your learning.

Taking control

Although we can’t control everything that happens to us, we often have more influence over our wellbeing than we realise. Even in difficult circumstances, there are usually things we can do to support our wellbeing. How we feel isn’t determined entirely by what happens in the world around us.

Of course, this is very easy to say, and taking control of our wellbeing is often more difficult to do. Sometimes, life throws up problems and barriers to healthy activities or we may not know how to take control of our particular circumstances. Even with the best of intentions, we sometimes start out planning to do something that is good for us and then find we have slipped back into old unhealthy habits.

How many of us have tried to adopt a healthier diet or spend less time on our phone and then realised that we are eating our way through a bar of chocolate or spending hours on Instagram?

What is true for our wellbeing is also true for our learning and academic performance. Even when we recognise that we could improve our skills, understanding and ability, finding the motivation to practise, work more or seek out support can be difficult. For some students, it can also be easy to assume that our academic ability is fixed and therefore that there is no point in trying to improve.

In this book, we will explore different ways to improve both your wellbeing and your learning. It is absolutely possible to do both – sometimes with the same intervention. Because our wellbeing and learning are linked, when you improve one, you can frequently improve the other as well.

Holistic model of learning and wellbeing

Performance of any kind is heavily influenced by a whole range of factors. Think about athletes in almost any professional sport. They don’t just practise the skills they need; they also make sure they are eating the right diet, getting enough sleep and resting. They need to have good relationships around them, whether that means bonding with teammates or making sure there is unity with their coaching team. Finally, top athletes devote time to ensuring that they have a positive mind-set and good self-belief.

These things matter for our ability to produce good performance. Just look at the number of soccer teams at the World Cup that are full of brilliant players but go on to underperform because the squad is divided, unhappy or bored.

The same is true of academic performance.

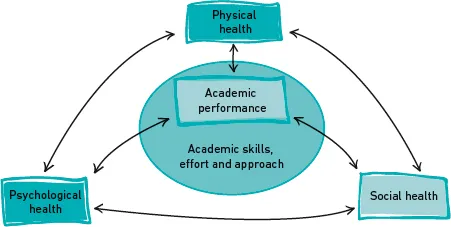

Take a look at the figure below [1].

This shows how physical health, psychological health and social health – when added to academic ability, effort and approach to learning – produce your overall academic performance.

But the model also shows two other important things.

First of all, the arrows run in both directions – not only does your wellbeing influence learning and performance but learning and performance also have an impact on your wellbeing. (In Chapter 4, we’ll look at how this works – but for now, just think about how a poor exam result can affect your psychological wellbeing.)

Second, each of these domains of wellbeing also affects each other. For example, your physical health impacts on your mood and your social health. Just think of times when you’ve felt ill; when this happens, it isn’t unusual for someone to feel emotionally down or irritable and to want to withdraw from other people until they feel well again. Sometimes, we can think about different aspects of ourselves as though they are unconnected. For instance, we may think that how we are managing our physical wellbeing and how we are performing academically are two completely separate things. But they are not – all of these things are constantly influencing each other.

So, if you want to improve your learning, it is worth looking at ways of improving your skills or increasing the amount of effort you’re putting in – we’ll look at this in Chapter 4.

But depending on your circumstances, you might also gain from getting better sleep or spending more time with friends.

Throughout the rest of this book, we’ll look at how we can make improvements in each of these areas and we’ll examine some of the evidence that shows us how improving our wellbeing can improve our learning and vice versa.

Before that, there are some key principles that are worth bearing in mind.

1. Nothing works for everyone – but everyone can find something that works for them

One of the great things about people is that we are all different from each other. Our diversity makes the world a better and more interesting place – but it also means that we respond differently to the same thing. You can see this really clearly when we look at interventions to help people who are experiencing problems with their mental health. If you look at the evidence from clinical trials and from practice, you will see that no treatment can resolve things for 100% of the population. Some will get better with one type of therapy, some from another and some will get no benefit from any type of therapy but may benefit from support to change their lifestyle.

This means that if you’ve already tried something and it hasn’t worked, don’t get downhearted. It just means you haven’t found the right thing for you – yet. If you keep experimenting and use support, you will find an approach that works for you.

2. Small steps win the race

When you want to improve things in your life, it can be tempting to throw everything overboard and to try to change everything at once. Unfortunately, what tends to happen when we do this is that we get overwhelmed, slip back into old habits and then give up. Human beings are generally creatures of habit and we will gravitate back to what we know, in terms of routine, even when it is bad for us.

That’s why it is important to begin by taking a few small, positive and achievable steps that help you to meet your needs in a more healthy way. By focussing ...