Venus

Room 30 of the National Gallery in London is like a giant jewellery box, a grand hall lined with crimson damask. On its walls hangs a collection of seventeenth-century Spanish ‘masterpieces’. There is one naked body in the room. It’s a young woman’s, reclining with her back to us, fully nude on a bed whose covers are agitated with the promise of sex. The ripples of silk and cotton echo the curves of her body. Her waist is impossibly small, her buttocks smooth and peachy, and her skin pearlescent, free from blemish, bruise or hair. Spectators ebb and flow to gaze at her body, seemingly unperturbed by their voyeurism. She doesn’t seem bothered either. A pot-bellied toddler with wings props up a mirror in front of her and on its charred surface you can just see her face, looking back at us, as we look at her body. She isn’t smiling, or scowling. She doesn’t look scared or anxious – or even surprised. She’s just seeing you looking at her, and she knows that’s the way it goes. After all, she has been here a long time. Gallery visitors amble past, the word ‘beautiful’ dropping casually from their lips and amateur artists copy her curves. Images of illustrious men surround her. Like sentinels, they flank her – one an archbishop, one a king. Do they guard her or own her? It’s hard to tell.

The woman is Venus, the mythological goddess of love and beauty. But if we want to be literal, it is a painting of a woman with no clothes on who in the late 1640s posed as the goddess Venus for the male artist Diego Velázquez who produced this for a male patron to enjoy, either in private or as an envy-stoking trophy in his art collection that would be looked at and discussed with other men in his elite circle. The context of its commission is undocumented, but it was in the collection of the Marqués del Carpio from 1651, shortly after its creation. It’s often described as the only surviving nude by the Spanish painter, a precious relic of a wealthy man’s display of status and power that escaped the punitive clampdown on sex and luxury in the religious climate of seventeenth-century Spain, perhaps painted in more tolerant Italy during a visit by the artist. (Velázquez took a risk in even producing it – the usual consequence for an artist painting a picture of a nude woman in seventeenth-century Spain was excommunication.)

The ‘Rokeby Venus’ is not the painting’s original name but recalls one of the places it was on display before arriving at the National Gallery in 1906. J.B.S. Morritt bought the painting in 1813 to hang in his collection in his house, Rokeby Park in Durham. He wrote to his friend Walter Scott in 1820 describing how its position above the fireplace made for a flattering play of light on Venus’ painted buttocks and observed how the picture made women feel uncomfortable.4 Before it entered a British collection, the painting had been owned by the Spanish president Manuel Godoy. It represents (at least in part) what a sequence of powerful male owners have historically wanted to look at unchallenged and untroubled. But for over a century, Velázquez’s Venus has been the ‘[British] nation’s Venus’, hanging in public among the tourists and the schoolchildren who circulate around the National Gallery. Guided groups are brought before her to revere the extraordinary achievements of the master artist, or to be teased by the play of gazes in the image – that Venus sees us seeing her – and, most of all, to be educated, enlightened and inspired by a picture of a woman with no clothes on.

The naked body of a woman in an art gallery is so normal, who would be pedantic enough to question it? This Venus is one of a bounteous number of female nudes currently hanging on the walls of the National Gallery. She’s an iconic goddess from classical mythology who represents love, fertility and beauty, and a reminder of our unerring belief in the cultural authority of ancient Greece and Rome. Venus means ‘Art’ with a capital ‘A’. Good art. High culture. Unimpeachable value. The inviolate tradition of beauty. Wander into the gallery shop and there she is again on the most popular postcard, a vehicle of the culture industry’s mythmaking. You can take her home on a poster or wear her printed on a cotton tote bag. She is a hot commodity.

The mythological goddess Venus may be shorthand for love, sex, beauty and fertility, all aspects of the human condition that warrant contemplation and celebration, but I can’t help but think that here – as the only nude surrounded by portraits of illustrious men – the Rokeby Venus seems to be cast as little more than a rich man’s plaything.

There’s an important story concerning the Rokeby Venus that’s nowhere to be found in Room 30 of the National Gallery. Get too close to her and alarms trill: she must be protected. She’s been hurt before. Look closely at her body and you’ll see the sutures. The scars are well-disguised, but the silver slithers stretch across her hips and back. In March 1914, the suffragette Mary Richardson walked into the National Gallery with a cleaver concealed in her coat and calmly approached Velázquez’s painting before slashing the canvas, leaving deep gashes in the alabaster surface of Venus’ body. Guards rushed to defend the gallery’s most prized nude, and Richardson was willingly detained while awaiting transfer to police custody.

The press seized on the attack and positioned it as a tale of two types of womanhood. On the one hand, there was the mutilated canvas that was animated into a passive victim: the gorgeous painted Venus who represented the silent and wounded paragon of ideal femininity. On the other was Mary Richardson, or ‘Slasher Mary’ as she became known: a monstrous example of deviant womanhood whose destructive impulse was taken as confirmation that suffragettes couldn’t be trusted with the business of political responsibility or respect for public property.

But Mary Richardson’s attack was not a mindless act of high-profile vandalism. She had a mission in destroying Venus, and justified her actions cogently:

Richardson was referring to the notoriously brutal treatment of imprisoned suffragettes, including their founder and leader Emmeline Pankhurst. While prisons inflicted torturous force-feeding on inmates, police were also beating and maiming women on the streets as they demanded to have a say in how their lives were governed. In her assault on Venus, Mary Richardson wanted to highlight the hypocrisy that a picture of a nude woman demanded more respect than the actual bodies of half of the population; her action was part of a wider guerrilla campaign of defacing public property that drew attention to the suffragettes’ aims. Years later she added that she also hated how men gawped at the painting all day.

By violating the ideal representation of passive, beautiful and enticing femininity, Richardson dismantled an illusion; she tore open its painted surfaces and showed that it could not bleed or suffer or die because, unlike the abused suffragette prisoners, it was an object and not a real body.

Visitors to London’s National Gallery very often don’t know this story. I’ve told it many times when teaching students or the general public, and it always piques mixed reactions. Indignation is the most common. ‘How could someone do something so sacrilegious to a beautiful work of art?’, they often ask, shaking their heads in disappointment. ‘Haven’t they done a good job at restoring her?’ is the other.

The intent behind Slasher Mary’s militant attack has long since been absorbed by the damask-lined walls of the National Gallery; the intervention is acknowledged in neither the accompanying wall text nor in the room’s interpretative materials. (Why would it be?, you might be asking yourself, but to me the silence speaks volumes about the way in which women’s critical voices become smothered and marginalised.)

When in 2018, the centenary year of the Representation of the People Act (which granted some women the right to vote), it became impossible not to mention the suffragette intervention, I heard a talk by a gallery educator in front of the painting, who dismissed any readings of sexual objectification that have since been levelled at the Rokeby Venus – as if the obstruction to women’s suffrage, and the viewing of women as sexual objects to satisfy a male patron’s gaze, could not possibly be related to one another.6

This wilful suppression of the gender politics written across the body of the Rokeby Venus makes me think that perhaps we don’t want inconvenient truths to get in the way of consuming the beautiful images we’ve become accustomed to enjoying, or that we don’t like being asked to accept that seductive highlights of culture contain more complex issues about gender, class, racism and capital behind their painted surfaces. Perhaps most of all, we really don’t want to consider how looking at art in our free time plays a part in all of this.

Maybe we feel like the public museum should be about uncomplicated and restorative leisure, diversion and the appreciation of human cultural achievement. Which they can be, but they are also about social aspiration and status, and about a complicated sense of virtue that we derive from visiting them. ‘Culture’ or ‘the arts’ is certainly one of the smuggest clubs to belong to. This is in part because appreciating the sort of art found in the National Gallery has often meant acquiring a new language of symbols, stories and references from texts such as the Bible and books of classical mythology – so the appreciation of art history beyond surface appearances has been contingent on access to privileged learning. Curators and directors of museums also privilege a certain sort of knowledge when they decide what goes on the walls, what remains in storage, what gets acquired to add to the collection, or how we change conversations about what images mean. Who is seen, how they are seen and who or what is erased from the walls of the gallery is a loaded issue.

Somewhere like London’s National Gallery is a place deeply informed by social aspiration. Since the gallery’s foundation in 1824, the working man could see the art collection of kings for free on any day of the week. Its founding ethos was to always be free of charge, and it was intentionally built in the midway point between the wealthy residential west of the city and the working-class slums in its east in order to be accessible for all. With its imposing, temple-like façade, the National Gallery sits in a space of pomp and pageantry: the building takes up one whole side of Trafalgar Square, a space designed and built to celebrate British military supremacy and Nelson’s defeat of Napoleon. Visitors get spat out onto the portico on the building’s façade as they exit, where the gilded monolith of Big Ben, at the political heart of the nation, strikes the eyeline. Immediately in front of us is Nelson’s Column, guarded by its yawning stone lions, and something of a connection is implied between the works on the walls of the gallery and the sense of stability in the British establishment. No wonder then that there are those who avidly defend the Rokeby Venus with a reverence that mingles with patriotism, aspiration and the satisfaction that looking at paintings like this is a morally virtuous and edifying pursuit. But how, you might wonder, does the proud display of a painting of a nude woman fit into this?

The original male owner of Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus was also driven to look at paintings like this one as a means of securing his status and political identity as a man in seventeenth-century Europe. In the 1650s, as is still the case now, looking at the Rokeby Venus was about education, taste, social aspiration and luxury. The presumed but undocumented first ‘owner’ of the Rokeby Venus was a social elite who built his status among other men by possessing and looking at beautiful objects – from intricately painted still life scenes to luscious female nudes. As art historian Maria Loh writes: ‘“Woman” was the cipher that enabled men to parade their prowess and power in front of one another.’7 (We might argue that looking at naked women is still a means of heteronormative male-bonding – take for example the ritual tradition of groups of men visiting strip clubs on stag, or bachelor, parties.)

The allure of Venus is also her classical pedigree, which speaks to Western culture’s faith in the pillars of ancient Greece and Rome as the benchmark for our understanding of ‘civilisation’. At best this has obscured (and at worst erased) the possibility of other expressions of taste, cultural achievement and beauty that derive from cultures outside of the ancient Mediterranean. Taste and beauty are therefore unerringly political issues: while each geographical region may have its own traditions of beauty, the default in global culture is always the classical white Venus. And this is important because our reverence for Venus and for classical culture has trickled down into the way in which we see women’s bodies generally and the expectations that we place on them.

In the house I grew up in, a poster of the Rokeby Venus hung above my bed in a gold frame. It was given to me by my mother when I was a teenager after I decided to study art history at university and I loved it. I had been seduced by Venus into internalising a patriarchal fantasy of womanhood. A child of the 1980s, I had grown up with beauty pageants on TV and men’s magazines hovering at the edges of my vision on the top shelf of the newsagent. The Rokeby Venus fitted right into the fantasies of girlhood I had been exposed to: she was a grown-up version of a Disney princess or teen mag model, and a more refined version of the Playboy pin-up. I wanted to learn more about her because on some level I thought I was meant to aspire to become her, because she was the apogee of what the world I lived in wanted me to be: fertile, graceful, desired and moreover that I would enjoy being desired before I atrophied into another archetype on my biologically predetermined destiny as a woman. And understanding Venus to me meant understanding and accessing the lofty echelons of art and culture that as a girl from a working-class family I was so fascinated by. But placing that image in my adolescent boudoir, that sanctuary of secrets and self-development, feels very wrong to me now.

After Mary Richardson’s assault on the canvas, Venus was put back together for our viewing pleasure. Order was restored. And Venus has been remodelled in every era since. I’d like us to open up the idea of Venus again and see how her image has spawned an avalanche of imitations within and beyond the walls of the gallery in pictures that have impacted the way women live and perceive their bodies.

Venus is an ubiquitous figure in collections of Western art around the globe. Her prime position and visibility in art and culture is a symptom of what art historian Griselda Pollock has called ‘culture’s deep, phallic unconscious’. But Venus is also in your pocket right now on a social media feed on your phone. She’s in a magazine you’ll pick up in the next couple of days or in a television commercial you’ll see in the next few hours. She’s on a billboard at the bus stop selling fast fashion and making girls feel bad about their breasts. She’s reminding you that you need to shave your legs so that men will like you. Or she’s educating boys on what to expect when they first get laid. Until recently she was in the newspaper in the UK, every day, on the third page.8 Venus is everywhere that there are women’s bodies representing ideas about female beauty, sex, wealth and status: from Renaissance paintings to the Victoria’s Secret runway; from cosmetics adverts to paintings by Picasso.

By looking more closely at what makes the mythical image of Venus, we can think about the repressed fears and desires that are projected onto the female body in our collective cultural consciousness. These include fears about our human physiology, how our bodies bleed, grow hair, and have diseases. I’d like us to think about how pictures of Venus can start conversations about racial and sexual difference and how the female body has been exploited to shape ideas about male genius and creativity. How it has stifled female sexuality and stoked racist assumptions about women of colour. How it has become a legitimate spectacle for objectification. I’d like us to think about how Venus has been employed to make ideal versions of femininity seem normal and to teach us patriarchy’s version of sex.

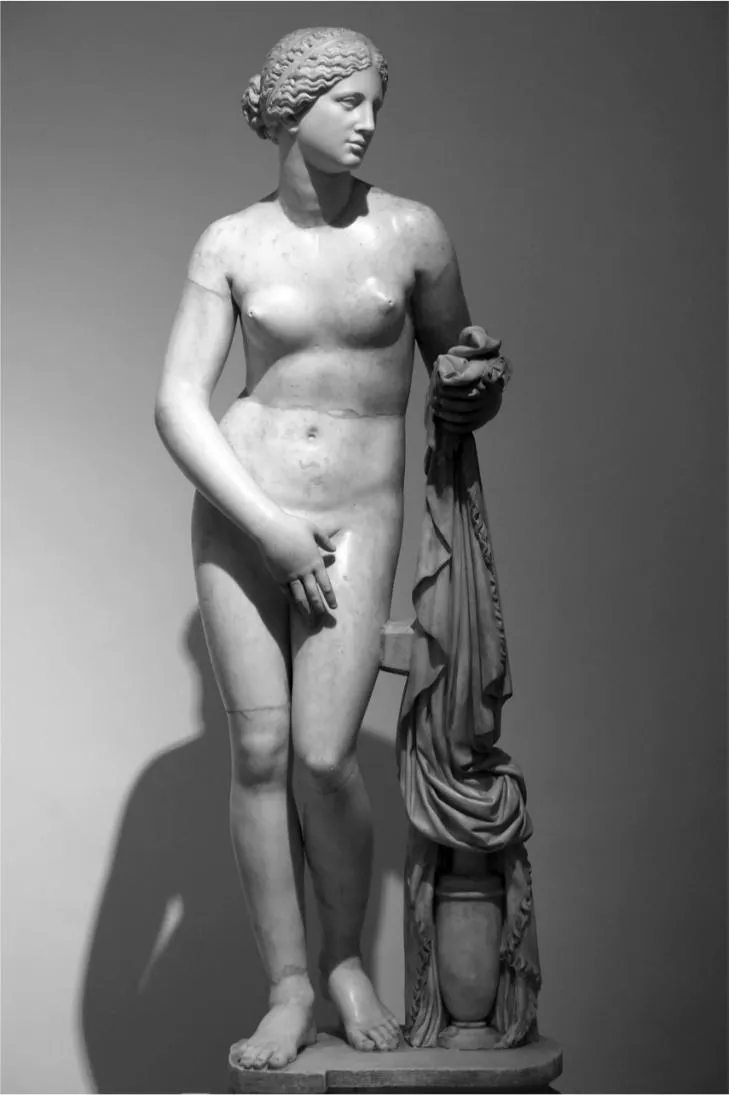

Venus is the Roman name for the Greek goddess Aphrodite, who probably derived from an earlier Mesopotamian deity of sexuality called Ishtar. Early depictions of the goddess are varied and sometimes show her as an armoured warrior who originally symbolised both war and love. But we’re going to meet her in her most well-known and most reproduced identity in a fourth century BCE sculpture that has inspired not only a whole history of art and contemporary visual culture but also the internalised fantasy of what womanhood should look like.

The first fully nude freestanding statue of Aphrodite appeared in 350 BCE. It’s called the ‘Knidian Aphrodite’ and is carved from marble. It was made by the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and was once a focus of devotion in a temple in Knidos in Greece which celebrated the cult of the goddess. It also, as far as I know, gives us the...