- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

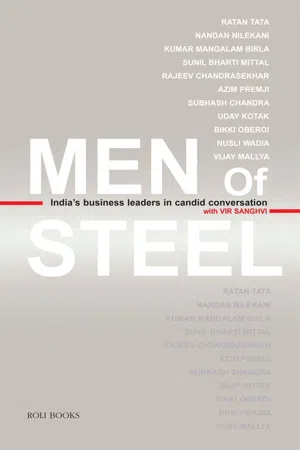

Men of Steel

About this book

Vir Sanghvi is probably the best-known Indian journalist of his generation. Founder editor of Bombay, his career has included editorship of Imprint, Sunday and The Hindustan Times. Sanghvi also has a parallel career as an award-winning TV interviewer and has hosted various successful shows on the Star TV network and on the NDTV news channel. One of India's premier food writer, his book Rude Food won the Cointreau Award, the international food business's Oscar, for Best Food Literature Book in the world. He is the author (along with Rudranghshu Mukherjee) of India Then and Now, also published by Roli Books. Madhavrao Scindia: A Life, a biography co-authored with Namita Bhandare is his latest publication.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Men of Steel by Vir Sanghvi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

winning india’s television trick

subhash chandra

Chairman, Zee Telefilms & Essel Group

s

Why, I ask Subhash Chandra, does he maintain that distinctive lock of white hair on the front of his head? Is it a fashion statement? Does it remind him of Indira Gandhi under whose benevolence he made many crores transacting Russian rice deals?

Subhash Chandra laughs. ‘Nothing like that,’ he says. ‘At first, it was natural, but now I have decided I like the look.’

The origin of the white tuft dates back, apparently, to Chandra’s struggling days. He was about to lease a factory when his partner backed out at the last moment. ‘Such was the tension and stress that this part of my hair turned white overnight. And it remained white,’ he recalls.

And now? I mean, he clearly dyes his hair black, so why is that single lock exempted from the treatment?

Chandra is not offended by what many businessmen might consider a rude question. ‘When I went to get my hair dyed, one day my barber told me that it might look better to keep this white. After all, that was how it had been even when the rest of my hair was black. So, I thought about it and I decided that he was probably right.’

‘I am an enterpreneuer. I know that I can create something from nothing.’

The episode should tell us three things about Chandra. One, that he enjoys his style statements. Two, that he is secure enough to discuss dyeing his hair. And three, that he hasn’t had it easy. There have been very tough times and moments of incredible stress.

Feeding the army to make a living

We know Subhash Chandra as the multi-millionaire father of the Indian commercial TV revolution. His Zee TV taught Indians what televized entertainment was all about. All the other commercial Hindi channels that followed have, in one way or another, been influenced by the legacy of Zee.

We know also that he is now astonishingly rich and well connected. Ask about his net worth and first he will duck the question, saying things like, ‘After the first crore, you stop counting.’ But when you push, he will admit that his family has a total worth of ‘around Rs 5,000 crore’. Nor will he talk about the contacts that allowed him to wage a successful battle against the global might of Rupert Murdoch. But once again, when you press, he will agree to discuss the battle even if it is only in general terms.

What we don’t realize is quite how small he was when he started out. His family are Marwaris who settled in the old undivided Punjab four generations ago. They entered the grain trade and by 1966, ran one dal mill and two cotton gins.

This was small time but still it wasn’t bad going. Until 1967, that is. His father lost heavily in cotton trading and the business’ entire net worth was wiped out. Plus, there were debts to suppliers and moneylenders.

At the time, Chandra was seventeen and in his first year at engineering college. His father pulled him out of university and told him that he had to find some way of helping the family business.

This was easier said than done. They were bankrupt, in debt and Subhash’s uncles were not sure that a seventeen-year-old had the answers to their problems.

As he remembers now, ‘We had no capital to run any business, so I struggled to find something that we could do without putting in our money. Fortunately, I met the district manager of the Food Corporation of India who took a liking to me and agreed to do some business with us.’

The army was a big buyer of grains, pulses and dry fruit. But it had extraordinarily high standards and the Food Corporation was unable to meet those levels. Chandra suggested that his family could upgrade the product (polishing rice, cleaning almonds, etc.) so that it met their standards. The corporation agreed and the family was back in business because he had found a way to add value without putting in any money.

‘Even then,’ he says, ‘we were not rich. We were still paying off debts and four families lived off the business.’

Then, in 1973-74, India had a bumper crop and the Food Corporation ran out of warehouses to store the grain. One solution was to make polythene tents to cover the mounds of wheat. Sensing an opportunity, Chandra entered this business, buying polythene sheets and then cutting them into tents. When this proved successful, he moved into making packaging material for agricultural pesticides.

In 1978, he leased an old plant in Delhi to manufacture fumigation sheets for chemicals and believed he had made the shift from agriculture to industry. In fact, he lost money on the plant. Undeterred, he imported a new technology and began making plastic tubes which he believed (correctly, as it turned out) would replace metal tubes as toothpaste containers. But even this experiment took time to take off and in the process the packaging business kept losing money.

But by 1981, these failures had ceased to worry Chandra. He had found a new way to make big money. And it had to do with grain.

Grain gain again, but with Russians

This is the bit where most profiles of Subhash Chandra suddenly begin to take on an uncertain air. We know that by 1985, he was very rich. We know also that it had to do with Russians and the Congress. But we don’t quite know exactly how he made his money.

Oddly enough, Chandra has no hesitation in talking about this phase. The way it worked, he says, was this: each year the Russians would import enormous quantities of rice from India. The deal was always routed through the government, which would indicate a rice trader of its choice.

In 1981, Indira Gandhi’s government told the Russians that they were to deal with Subhash Chandra. He made crores in profit on the first transaction and though he does not say so, it seems probable that some of those crores were shared with the Congress. At any rate, Mrs Gandhi was so pleased with Chandra’s performance that he got the Russian rice deal every single year during her second term in office.

When Rajiv Gandhi took over, Chandra did the deal the first year and then, at the government’s request, took on a 50 per cent partner in the second year. By the third year, the Congress had its own bagmen in place and he bowed out.

Is it all right to ask how much money he made on these deals, I wonder, a little tentatively. Some of it may have gone into Swiss bank accounts and I wouldn’t want to embarrass him.

‘No, not at all,’ says Chandra. ‘We took all our profits legally. They are there in our books. Many years later, when they launched income tax and FERA investigations against me, nobody was able to find anything illegal in those transactions.’

So, how much did he really make on the Russian rice deals?

‘A lot of money. Lots of money. About Rs 70-80 crore, which was worth even more in those days than it is today.’

After all those years at industrial diversification, Chandra was a millionaire. And the profits had not come from industry or packaging.

They had come from the business that was in his blood: grain trading.

A Marwari ritual

What do you do when you have Rs 80 crore in cash? Either you put it into your business or you look for new investments.

Chandra did both. But first, he made his brothers go through a traditional Marwari ritual calle ‘pani mein namak daalna’ or literally putting salt in water. It is, he says, a sacred vow within the Marwari trading community. Once you agree to do something during this ritual, you can never back out.

The vow was: the family would be completely legit from now on. There would be no businesses that were at all underhand. Instead, they would try and do everything by the book.

As part of this endeavour, they opened the Essel Packaging plant and made huge investments in property including 800 acres in Gurgaon – Subhash had the foresight to see that as Delhi expanded, this would be a growth area.

‘I think the decisions we made during that period have served us well,’ he says. ‘Essel Packaging now has twelve plants in eight countries. We are developing Essel Towers in Gurgaon. The land we bought in Mumbai shot up in value and we built Essel World on part of it. But the best thing we did was the pani mein namak daalna. So many governments have tried to investigate me but they have never found anything because I have nothing to hide.’

It was one of these decisions that led to the creation of Zee TV. Chandra built Essel World as a sort of Indian Disneyland in 1989-90 and was devastated when it failed to get the footfalls he had predicted. Consumer research led him to the conclusion that while people wanted to be entertained, they were not willing to drive two hours for this entertainment.

‘The obvious thing from a business point of view was to take entertainment to people if people were not going to come to your entertainment,’ he remembers. ‘In those days, video was very big. So, I planned to equip a fleet of video vans that would tour the countryside charging people money to watch the videos.’

In retrospect, it doesn’t seem like such a great idea, but at least it got Chandra focused on video and TV. The second idea was to run a terrestrial television station just outside the Indian border (in Nepal, perhaps) and to beam programming into the country. This too was abandoned when he realized the limitation of a terrestrial beam: it wouldn’t reach any major Indian city.

Then, in 1991, watching CNN during the Gulf War, it finally came to him: why not use this new satellite technology to beam programming to India?

A STAR on the horizon

How does a wealthy Indian who has made his money in the grain trade and whose industrial experience consists of manufacturing toothpaste tubes enter the international television business?

Chandra had no idea. But he intended to find out.

He heard about Asiasat and chased the chief executive, finally locating him in the Christmas of 1991 when the man was on holiday in Canada. The Asiasat boss told Chandra that all his transponders had been leased to a new company called Satellite Television Asian Region, or STAR for short. If he wanted to run his own TV station, he needed to call STAR.

Repeated approaches to STAR headquarters in Hong Kong rarely moved higher than the level of junior executives. Eventually, because of Chandra’s sheer persistence, they agreed to fix a meeting with Richard Li, son of Li Ka Shing, the owner of STAR. It was not a pleasant experience.

‘We were all sitting in a room, waiting for a long time,’ remembers Chandra, ‘when Richard Li walked in. His executives told him that we were interested in an Indian channel. “India!” said Richard. “There is no money in India. I have no interest in India.” Naturally, I was flabbergasted but kept my patience.’

The younger Li then asked Chandra, ‘How much will you pay for this transponder? I don’t want to do a joint venture with you so you can take the transponder on your own.’

Chandra said that a price of $1.2 million had been agreed with STAR executives.

‘Not enough,’ said Richard Li.

‘I don’t know what came over me,’ recalls Chandra, ‘but I got up and told him that I would take it for 5 million dollars. There was just one catch. The deal was only valid for twenty-four hours.’

If we were dealing with fiction, then Li would have said yes on the spot and Chandra would have got his transponder. But real life is never like that.

Richard Li refused to take Chandra seriously and left the room.

Enter Rupert Murdoch

By then, STAR had hired a merchant banker to advise it on potential Indian partners. The banker was scornful of Chandra who had no media credentials and sent STAR to talk to major Indian newspaper groups. But nobody was willing to pay as much as Chandra. On 21 May 1992, Richard Li finally came to India, was taken to see the Essel packaging factory, was made aware that Essel supplied to Levers’, Procter & Gamble and other international companies, and finally overcame his reservations about Chandra.

And Zee TV was born.

Chandra’s original business plan hoped to tap into the Rs 90 crore advertising market for video. This was not big money by...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Bookname

- Other Lotus Titles

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- The World is Flat

- Gennext Icon

- The Sim-sim Saga

- Fighting a Good Fight

- There’s More to Life

- Winning India’s Television Trick

- Raising the Luxury Bar

- Of Friends and Foes

- Man of Substance

- Fishing for more Business: The Kingfisher Way

- It’s Lonely at the Top

- Backcover