![]()

1

Seizing the Momentum to Reshape Agriculture for Nutrition

Shenggen Fan, Sivan Yosef* and Rajul Pandya-lorch

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Washington, DC, USA

Introduction

The importance of agriculture to human welfare cannot be overstated. At its most basic level, agriculture, which includes not only plant cultivation but also animal husbandry, fisheries, and any activity occurring along the value chain from production to consumption, is the source of food and sustenance for the world’s population. Ancient societies began cultivating and domesticating crops, livestock, and fish thousands of years ago. Key agricultural achievements such as irrigation, fertilizers, and selective breeding helped agriculture flourish in all parts of the globe under diverse, and at times barren, landscapes, enabling local populations to thrive. For much of history, humans have viewed agriculture as a tool of survival by way of providing enough calories.

This singular goal of agriculture, as a way of overcoming famine, carried over through the centuries and shaped the aims of perhaps the most famous achievement of modern agriculture, the Green Revolution, which focused on boosting agricultural production and productivity by investing in science and technology (to improve staple crops such as rice, wheat, and maize), irrigation, roads, and fertilizer production (Spielman and Pandya-Lorch, 2009). From 1960 to 1990, this series of investments improved access to food and/or provided a critical source of income for approximately 1 billion people (Evenson et al., 2006).

But for all its achievements in the areas of production and productivity, and as a source of raw materials for industry, one critical contribution of agriculture has not received sufficient attention: nutrition. Food contains more than just calories. It delivers macronutrients, such as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, as well as micronutrients, or vitamins and minerals. Humans need these micronutrients throughout their entire life cycle, though most critically from conception to 2 years of age, in order to achieve good growth and development. The taste and quality of highly nutritious food also affects people’s demand for it. Beyond food, agriculture also provides a critical source of income for the world’s poorest people, enabling them to purchase a wide array of healthy foods, healthcare, and education. It is linked to nutrition through myriad other ways, including by shaping gender roles, impacting food prices, and more. Despite these intractable links between agriculture and nutrition, the global community has historically been slow to get on board in expanding its vision of what agriculture can really do.

The consequences of inaction are staggeringly high. In 2017, 821 million people were undernourished (FAO et al., 2018). Stunting (being too short for one’s age) affected more than one in five children, or 151 million children around the world, under 5 years of age (FAO et al., 2018). An additional 51 million children were affected by wasting, being too thin for their height. Among women of reproductive age, 33% were affected by anemia (FAO et al., 2018). What is more, poor nutrition has lifelong and generations-long implications. Children who are undernourished at a young age start school later and complete fewer grade levels later in childhood (Alderman et al., 2006), and receive lower wages as adults (Behrman et al., 2004; Maluccio et al., 2009). Poorly nourished women give birth to poorly nourished children, perpetuating the cycle.

Agriculture feeds 7.6 billion people, and employs 69% of populations in low-income countries (FAO, 2011; ILO, 2017). It therefore has a vast potential to impact nutrition positively, a potential that has not been fully tapped. In response to this gap, individuals, organizations, and communities have begun to scale up their efforts to link agriculture and nutrition. This past decade has seen a flurry of activity to build up the evidence base on the ways in which agricultural and food systems can be redesigned and re-imagined for the benefit of nutrition.

This book seizes upon that momentum. It brings together research and programmatic advances, and policy developments at the national, regional, and global levels, during the past 5–10 years that have brought the two sectors closer together. It draws heavily from the International Food Policy Research Institute’s (IFPRI) own research, as well as that of the growing agriculture–nutrition academic community, with supplementary insights from implementing and normative organizations. By highlighting the achievements – and setbacks – it offers lessons for those who want to engage in this work, whether within the policy arena, academia, or programming, and sets the stage for closing knowledge gaps and scaling up successes that can transform food systems and improve the nutrition of billions of people.

Conceptual Links Between Agriculture and Nutrition

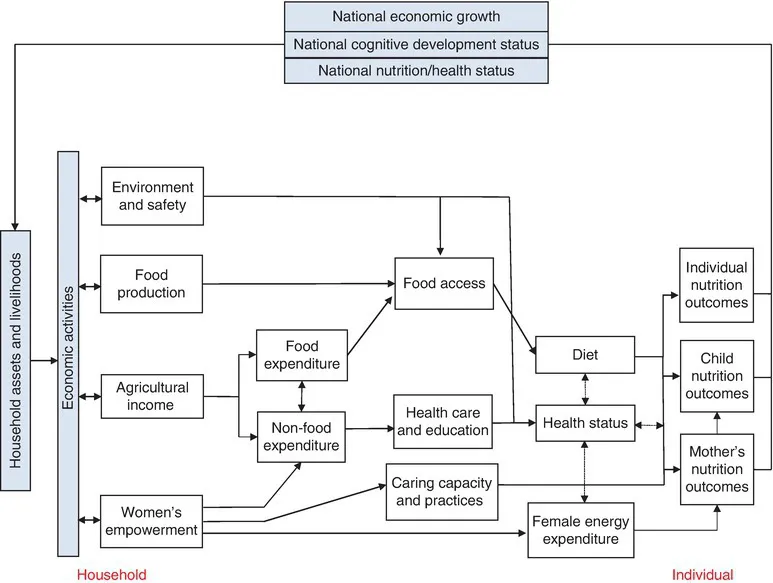

The authors in this volume introduce a range of conceptual frameworks, reflecting their different disciplines, to describe the relationship between agriculture and nutrition. Figure 1.1 shows these various relationships, as well as the feedback loop from individual nutrition outcomes to national economic growth, and the nutrition, health, and development of populations.

As noted above, agriculture is ultimately the source of food, delivering energy, macronutrients, and micronutrients essential for growth. Diversity in agricultural production is important along with total supply: areas with higher agricultural diversity produce more nutrients (Jessica Fanzo, see Chapter 4, this volume). Also, since many food producers consume what they produce, production diversity is strongly and positively associated with dietary diversity among young children (Kumar et al., 2015).

Agriculture is also a source of income for farmers that they can use to purchase healthy, diverse foods, as well as services that are integral to maintaining nutrition, including healthcare and education. Conversely, this income can be also used to purchase processed, unhealthy foods that can lead to overweight, obesity, and ill health (Olivier Ecker, see Chapter 8). One instrument that can affect the linkage between agriculture and nutrition, explored in Chapter 2 by Derek Headey and William Masters, is the relative cost of nutritious foods. The authors ponder whether different sources of calories have different levels of affordability. They compare the costliness of cereals, roots/tubers, fruits, vegetables, legumes, and animal-source foods in low-income versus wealthier countries. Furthermore, they probe the extent to which high prices hinder people from consuming certain foods.

A number of pathways from agriculture to nutrition consider the role of gender, as focused on by Hazel Malapit in Chapter 6. Participation in agriculture may give women increased access to and decision-making power over resources, such as income, and agricultural assets such as land and livestock, which in turn can increase their social status and empowerment to allocate food, health, and care within their households (Kadiyala et al., 2014). Women’s time, and the trade-offs they make when they participate in agriculture, such as spending time on childcare (or not), can positively or negatively affect their own nutritional status and that of their children. Exposure to occupational health hazards, and excessive energy expenditure can also impact women’s health and nutrition and the transmission of undernutrition to their future children (Kadiyala et al., 2014). Given these links, many interventions focus on women as beneficiaries, but should the aim to empower women actually expand more broadly to achieving gender equality within households? Malapit explores the recent research and program findings on this very question.

The impact of agricultural hazards goes beyond gender to affect producers’ health through zoonotic and vector-borne diseases (since agriculture also includes animal husbandry), as well as consumer health through food safety. Agricultural practices may also lead to environmental degradation and subsequently poor health and nutrition, especially as many parts of the world face additional challenges like climate change (Daniel Raiten and Gerald Combs, see Chapter 7). The agricultural system may exacerbate inequality, such as when agricultural policies favor large farms, marginalizing smallholders; or contract farming results in unequal power dynamics (Dury et al., 2014).

One useful way of envisaging the links between agriculture and nutrition is by using a value-chain approach, which considers how nutrition can be retained in or added to food from production and processing to marketing and consumption. In Chapter 3, Summer Allen, Mar Maestre, and Aulo Gelli explore how value chains can build up the supply of nutritious food by improving agriculture-related infrastructure and processes, such as transportation and storage; or boost demand by, for example, promoting behavior change among consumers. The authors envision great potential for scaling up nutrition-driven value chains.

A Nascent Field

Although the agriculture–nutrition relationship was probed early on by some academics, their questions mostly focused on food security or calorie intake. As such, academic and policy interest in a broad range of agriculture–nutrition linkages is fairly recent. As described above, throughout most of the 20th century, the main focus of agricultural efforts was to address food shortages by increasing production (World Bank, 2014). Up until the 1980s, most economists still focused solely on strategies to produce more energy to meet consumer demand, under the assumption that nutrition did not play a role in consumer preferences.

The nutrition community had a similarly myopic view, focusing its efforts in the 1940s–1960s on addressing protein deficiency. In the 1970s, nutritionists embraced multisectorality, advocating for the embedding of nutrition cells into larger government programs or divisions for agriculture or health within developing countries (Gillespie and Harris, 2016). This effort was largely abandoned a decade later due to lack of funding, capacity, political attention to nutrition, and poor project performance (World Bank, 2014).

In the 1990s, a small segment of the development community began to explore a wider agriculture–nutrition nexus, mainly through a focus on delivering micronutrients by consuming specific foods. In Chapter 5, Howarth Bouis, Amy Saltzman, and Ekin Birol take us through the journey of biofortification, the process of increasing the density of vitamins and minerals in a crop through plant breeding, transgenic techniques, or agronomic practices, which began in the early 1990s at CGIAR. These efforts, at the time anyway, still operated within a niche segment of the international development community. By now, nutrition professionals had shifted focus to delivering nutrition-specific interventions; agriculture professionals, on the other hand, continued on the path to improving productivity and market-led growth (World Bank, 2014). From 1973 onwards, for example, the World Bank carried out 40 agriculture projects that contained nutrition components, but nutrition was not a project development objective in any of these.

The early 2010s seemed to signal a turning point. The power of the conceptual links between agriculture and nutrition was increasingly recognized, as were the shortcomings in their real-life application. The research community released several key reviews. Masset et al. (2011) concluded that there was a lack of empirical evidence on nutrition status outcomes of agricultural interventions, mainly due to poor study designs. Hawkes et al. (2012) undertook a mapping and gap analysis of 151 research projects, one-third of which were led by CGIAR, which revealed critical research gaps on such topics as value chains, agriculture’s indirect effects on nutrition, and multisectoral governance and policy processes. Turner et al. (2013) confirmed these results.

In 2011, IFPRI held a global policy consultation on ‘Leveraging Agriculture for Improving Nutrition and Health’ in New Delhi, India. The consultation gave momentum to launch the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH), a large program which undertakes work on healthy food systems, biofortification, food safety, supportive policies and programs, and human health. It also prompted the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (UN) to conduct an internal evaluation of its nutrition work, guided the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) to expand bilateral funding into the agriculture–nutrition nexus, and changed professional discourse, by ‘boosting the frequency of reference to cross-sector impacts on both nutrition and health’ (Paarlberg, 2012). The research underlying this conference was compiled and released by Fan and Pandya-Lorch (2012).

This book focuses on the advances in agriculture and nutrition from this critical turning point, exploring research, policy, and programmatic advances during the past 5–10 years to review what has c...