![]()

1

Jesus: Reliably surprising, generously orthodox

DAVID F. FORD

It is appropriate that a book on generously orthodox Christian theology should begin with Jesus. If generous orthodoxy, or any other account of faith and understanding, is to have any Christian validity it must ring true with who Jesus is and what he has done and continues to do.

As this book was brought together, generous orthodoxy was initally described as an approach to theology that ‘has deep roots in the Scriptures and the great tradition of Christian orthodoxy, wants to learn from the riches of the whole church and is always expectant for the Holy Spirit who makes all things new’. That suggests something of good theology’s depth – here, scriptural depth; its length – the long tradition of Christian orthodoxy; its breadth – the riches of the whole Church; and its height – the Holy Spirit poured out from on high on all flesh. The imagery of the Spirit in Scripture in fact reaches in all directions: in spatial imagery, the wind of the Spirit blows where it will from any direction, the water of the Spirit wells up from the depths to eternal life; and, in temporal terms, the Spirit inspires the prophets and others in the past, is the foretaste of what is to come, and in the present can lead into all the truth, give all sorts of gifts, produce the fruit of ‘love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control’ (Galatians 5.22–23), unite us with Jesus and with each other in love and peace, and, in short, is the ultimate reality of generous abundance. As the Gospel of John says, the Spirit is given ‘without measure’ (John 3.34).

And Jesus is intrinsic to each of these elements of a generous orthodoxy.

As regards Scripture, it is not just that he is the central figure of the New Testament, and not just that the Old Testament was his own Scripture, shaping him deeply; in addition, what scholars call the intertextuality between the two is so pervasive that one simply cannot adequately understand the New Testament witness to Jesus without going deeper and deeper into the Old Testament. My favourite work of New Testament scholarship in recent years is Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels by Richard Hays. It is a profound inquiry into how the New Testament is illuminated by its multiple, rich echoes of the Old Testament in stories, imagery, terms, titles, patterns and a God-centred figural imagination.

If the Church today is to be orthodox it needs to be as deeply immersed in the Old Testament as Jesus was. The sad fact is that the Old Testament is often neglected, sometimes omitted from readings in services, and, in my experience, seldom preached on. One of the most powerful and convincing advocates of the immense importance of the Old Testament is Ellen Davis, a colleague of Richard Hays at Duke University. Her book Wondrous Depth: Preaching the Old Testament is a scholarly and passionate call to preach the Old Testament, together with some superb examples of her own sermons.1 Her more recent collection, Preaching the Luminous Word: Biblical Sermons and Homiletical Essays, has some of the best sermons I have ever read or heard.2 Best of all is her recent major work, Opening Israel’s Scriptures, which moves through the whole Old Testament/Hebrew Bible in short, wise and theologically rich chapters.3 Both Davis and Hays figure high on my list of outstanding exemplars of generous orthodoxy.

As regards the long tradition of Christian orthodoxy, for the first half millennium or so the main doctrinal debates in the Church circled around Jesus. They led to the Council of Nicaea in 325, and its decision on the full divinity of Jesus as being of one substance (homoousios) with the Father; the Council of Chalcedon (451), and its definition of the full humanity in relation to the full divinity of Jesus; and parallel developments in decisions about the Holy Spirit that together led to the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity. And, in the millennium and a half since then, Jesus has remained central to mainstream Christianity, as represented by Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant and, more recently, Pentecostal Churches.

That diversity leads into learning from the riches of the whole Church. Each of those traditions, and their numerous sub-traditions, has things to teach the others about Jesus. I suspect few of us who have been privileged to engage in any depth with the literature, the communities and the faithful members of Christian traditions other than our own would deny that there is much to be learned from them. I myself think back to my time living in Birmingham and two remarkable women, Miss Fisher and Miss Reeve, then in their seventies, who had founded Hockley Pentecostal Church there during the Second World War. They made it a place where, in an open service on Saturday evenings, people came from far and wide to take part in worship where Jesus was Lord, Saviour, healer and giver of the Holy Spirit. And, almost without fail, Miss Reeve at some point would give a prophecy, almost always touching, in a variety of biblical imagery, on the abundance of God’s love and gifts. I was intrigued by the fact that, in a tradition that did not put much emphasis on the Lord’s Supper, or Holy Communion, the imagery she used was so often that of the meal to which Jesus invites us. ‘My children, I have prepared a feast for you, and you have come, but you have only nibbled at the first course. There is so much more I have for you! Come and feast on the abundance I provide!’ Her Jesus was the very embodiment of generous and attractive love.

On a more academic note regarding the riches of the whole Church, it has been one of the many delights of my time as a university teacher to see the way in which one whose PhD I was privileged to supervise, the Catholic lay theologian Professor Paul Murray of Durham University, has in recent years pioneered the movement called Receptive Ecumenism. It is an excellent example of generous orthodoxy in practice, encouraging each Christian tradition to be hospitable towards, and learn from, the others, and I hope that it is taken up throughout the worldwide Church, as it deserves to be – and that Paul Murray is a prophet who is heeded in his own country, too.4

And, finally, there is the Holy Spirit who makes all things new. Clearly, in the New Testament, Jesus and the Holy Spirit are inseparable, from Mary’s conception of Jesus to his resurrection and ascension. It is especially significant that the Gospel of John, which I (along with most scholars) take to be the latest of the four canonical Gospels, and which I (along with some scholars) understand to have been written with knowledge of the other three, Synoptic, Gospels, both has most emphasis on the person of Jesus (most vividly in the series of ‘I am’ sayings) and also has most to say about the Holy Spirit. This Gospel, which seems to have been written out of eyewitness testimony, and out of reading and rereading the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Jewish Hebrew Scriptures), the Synoptic Gospels and, I think (along with a few scholars), Paul’s letters too, all combined with many years of reflection, prayer and Christian living, unites Jesus and the Spirit as closely and intimately as possible – most clearly in the resurrected Jesus himself breathing the Spirit into his disciples (John 20.19–23).5

So, not only are all those marks of generous orthodoxy inseparable from Jesus, but he is utterly vital to each. Having, I hope, established that, in the rest of this chapter I want to do three things.

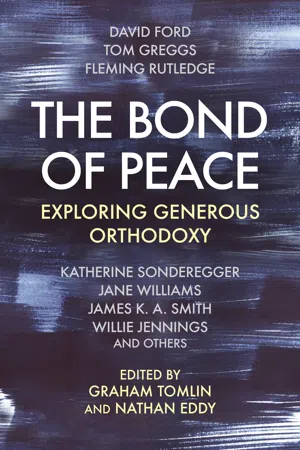

First, I will recommend the theology of Hans Frei, whom I consider the twentieth-century American theologian who has most generative potential for twenty-first-century Christian theology. He was one of my own teachers, and he had a great influence on numerous others too during his years as a professor at Yale.6 It is especially appropriate to focus on Frei in this book because it was he who gave fresh currency to the term ‘generous orthodoxy’ (he took it from his own teacher at Yale, Robert Calhoun).7 Frei used it to describe his own position; and many others have found it attractive. But, like other such phrases, it can be taken to mean many things, and can be used as a slogan for very different positions. I will briefly give an account of three key elements in Frei’s generously orthodox theology that I would propose as essentials.

Second, I will try to move beyond Frei’s largely synoptic focus to a consideration of the Gospel of John as perhaps the best New Testament example of generous orthodoxy in relation to Jesus.

Finally, I will supplement the term ‘generous orthodoxy’ as applied to Jesus with a phrase that I have deliberately put first ahead of that in my title: ‘reliably surprising’.

Frei and generous orthodoxy

So, first, what has Frei to contribute to twenty-first-century generous orthodoxy? Out of many possible points, I will confine myself to three, and even these will be extremely condensed.8

The first point is his approach to who Jesus is. His book The Identity of Jesus Christ sums this up well. The basic argument is as follows. The Gospels are primarily about Jesus, and they testify to his identity through telling his story in history-like, realistic narrative form. This conveys who he is through his intentional actions, interactions and what happens to him, and inseparable from this story is its conclusion in his resurrection, which is presented as God acting and Jesus appearing. The meaning of the story is found through following its characters and events in their interplay, not, for example, by finding some conceptual or moral sense that happens to be expressed in this narrative form, nor by seeking to reconstruct the history behind it by historical critical methods.

The second point is that all this unavoidably raises simultaneously the questions of historical and of theological truth, and faces readers with a decision, which is sharpest and most significant in relation to the resurrection. As Mike Higton, in his fine Foreword to the updated and expanded edition of Frei’s book, puts it:

Frei allows that it is conceivable that the resurrection could be falsified, but not that it could be conclusively verified by historical critical methods, which rightly are concerned with ‘the kinds of things that happen’ and therefore not suited to something qualitatively unique and conceived as the one-off pivot on which history turns. It is true both that historical testimony is relevant to this event and person, and therefore critical historical cross-examination is appropriate, and that God is essential to the character of this event and person, and therefore, as Higton later says:

The careful, thorough case that Frei makes out for this needs to be followed in detail. His remarkable achievement is to have offered the most convincing answer I know to the question of the relationship between what is sometimes called the Jesus of history and the Christ of faith. It is backed up by his major work on hermeneutics, The Eclipse of Biblical Narrative, which describes in detail the various ways in which historians and theologians, conservatives, liberals and radicals, failed to do justice to the particularity of the Gospel narratives during the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The third point is that Frei in his Types of Christian Theology offers a map of modern theology that is better than any other I know, including those vague, largely political and generally unhelpful categories: conservative, liberal and radical. (It is one of the virtues of the description ‘generous orthodoxy’ that its wiser uses also manage to transcend those categories, enabling healthy theology to be conservative in some respects, liberal in others – liberality and generosity go together – and radical in yet others.) The strengths of Frei’s five-type continuum are many, but, for my purposes here, two are most important: it pivots around how narrative portrayal of Jesus in the Gospels is understood a...