eBook - ePub

The Stuff of Spectatorship

Material Cultures of Film and Television

- 354 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Film and television create worlds, but they are also of a world, a world that is made up of stuff, to which humans attach meaning. Think of the last time you watched a movie: the chair you sat in, the snacks you ate, the people around you, maybe the beer or joint you consumed to help you unwind—all this stuff shaped your experience of media and its influence on you. The material culture around film and television changes how we make sense of their content, not to mention the very concepts of the mediums. Focusing on material cultures of film and television reception, The Stuff of Spectatorship argues that the things we share space with and consume as we consume television and film influence the meaning we gather from them. This book examines the roles that six different material cultures have played in film and television culture since the 1970s—including video marketing, branded merchandise, drugs and alcohol, and even gun violence—and shows how objects considered peripheral to film and television culture are in fact central to its past and future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Stuff of Spectatorship by Caetlin Benson-Allott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Collecting and Recollecting

Battlestar Galactica through Video’s Varied Technologies of Memory

On September 17, 1978, Battlestar Galactica (ABC, 1978–1979) was supposed to be the biggest thing on television. Billed as “the most fantastic space adventure ever filmed,” the three-hour series premiere was also ABC’s Sunday Night Movie of the Week, intended to capitalize on the recent success of George Lucas’s Star Wars (1977).1 Television and print advertisements built anticipation for the debut, as did stories in Newsweek, People, TV Guide, and other magazines.2 But the grand premiere was interrupted. At approximately 10:00 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time, ABC temporarily cut in on their space opera with a newsflash announcing the signing of the Camp David Accords, a surprise breakthrough in the long-term hostilities between Egypt and Israel. Some viewers were frustrated by the intrusion, others amused by the uncanny coincidence it created between fantasy and real-world diplomacy. For Battlestar Galactica begins with a peace treaty between twelve human planetary colonies and their long-standing enemies, the warmongering robot Cylons. As it happens, the Cylon armistice is a ruse, designed to distract the humans while the Cylons destroy all their colonies and most of their military. That conceit probably inclined ABC viewers to receive the Camp David Accords ironically at best, cynically at worst. But contemporary viewers cannot share their reaction to the historic juxtaposition, because no off-the-air recordings of it remain.

With those recordings, a certain relationship to television history was also lost. Battlestar Galactica is still widely available—it has been released on every major home video platform since VHS—but different video platforms facilitate different forms of cultural memory, including none at all. As opposed to personal memory, cultural memory refers to artistic, institutional, and other texts that serve as mnemonics to trigger ideas about historical events. How one accesses television history on video influences a series’ relationship to both of those terms—television and history—as it can position the show as either an important facet of cultural memory or merely entertainment.

When Battlestar Galactica premiered, television was a genre largely understood through hermeneutics of liveness, ephemerality, and flow, but recording fixes TV as history, or rather histories.3 All video technologies can be what Marita Sturken calls “technologies of memory,” or rather memories, since each new video format generates a new history for the series distributed on it.4 Video technologies are not self-similar technologies, in other words, and they do not offer the same kinds of access to content. Our relationship to television history and, through it, cultural history changes depending on whether we access it through off-the-air recordings, prerecorded videocassettes, DVD or Blu-ray season box sets, or digital files delivered through a video-on-demand platform. When I watch an off-the-air recording of a television program, I inevitably see traces of its broadcast history within the televisual flow of series, commercials, and news flashes, no matter how scrupulously the person who made the recording may have tried to edit out such interstices. A prerecorded videocassette of the same episode isolates it from both history and its series, compromising television’s intrinsic seriality and intertextuality to create a stand-alone commodity. When I watch that episode as part of a prerecorded DVD or Blu-ray season box set, I see it through the logic and economy of the “Collector’s Edition,” which governs both these formats. The box set’s distributor imbues their product with the ahistorical ideology of collection through auteurist bonus features that promote the artistic value of the show. These supplements are unavailable when one streams or downloads the program.5 Video-on-demand platforms smooth out differences of production, distribution, and access, making all content available in the same way and enabling a form of shallow spectatorship that I call transient viewing.

By reexamining the pilot episode of Battlestar Galactica through each of the videographic technologies of memory outlined here, this chapter argues that Battlestar Galactica’s status as historical document and televisual text changes depending on its distribution technology. This is not to say that the medium is the message, however, or that “the ‘content’ of any medium is always another medium.”6 With all due respect to McLuhan, my argument is not so technodeterminist as his. Rather, I posit that the commodity forms—which is to say, the commercial framing—of different video formats change consumers’ perception of television’s historical value.7 Video as we’ve constructed it changes what we value when we value television, meaning both television programming and television history. This distinction is especially important for legacy television, series originally broadcast on over-the-air networks or cable channels. Many scholars are examining the changes that new platforms create in television production. Fewer analyze how these changes affect legacy television, and almost none have studied the way that video-on-demand platforms affect viewers’ conception of television history or its place in cultural memory.8 Therefore this chapter takes up the crucial work of analyzing video formats not just in terms of access—perhaps the key term of video studies—but in terms of value.9 As television historians, theorists, and fans, we must ask what it is we are being shown when we watch old television on new media.

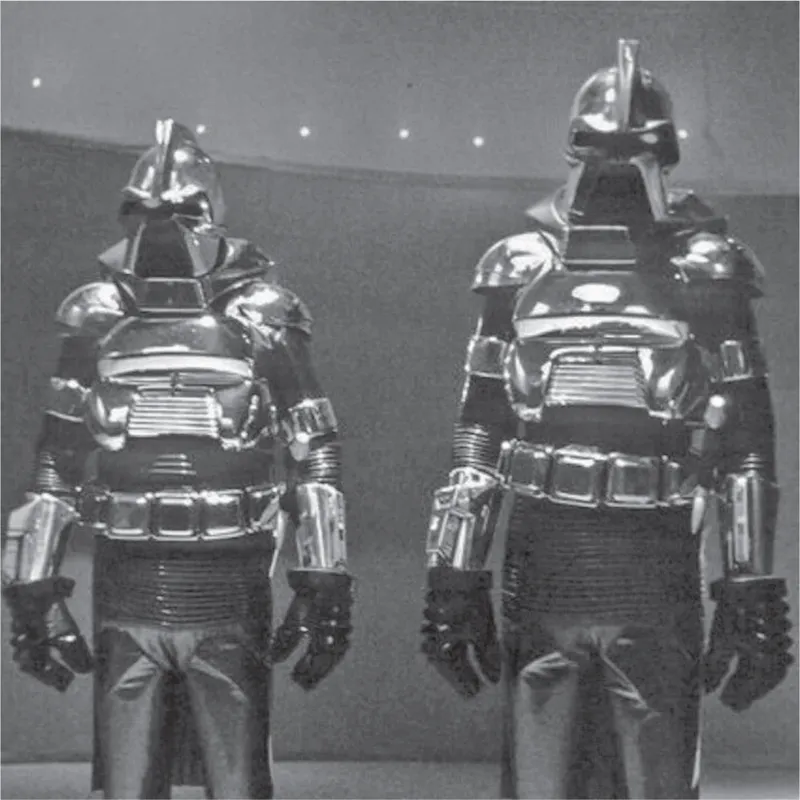

OFF-THE-AIR RECORDING AND HISTORICAL SIMULATION

In 1978, less than 2 percent of US households had VCRs, yet the Battlestar Galactica premiere was one of the most video-worthy events of the emerging home video era.10 In the 1970s, VCRs were marketed as time-shifting devices; consumers mostly used them to record television programs for later viewing. Battlestar Galactica was heavily promoted as an important, big-budget series and calibrated to appeal to multiple generations, genders, and racial and ethnic groups. The series boasted cutting-edge special effects by John Dykstra, who had recently won an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects for Star Wars. Having Dykstra and his team on board positioned Battlestar Galactica as the de facto sequel to Lucas’s blockbuster, then the second-highest-grossing film ever made.11 As mentioned, the series pilot, “Saga of a Star World,” begins with the signing of a false truce between the twelve human planetary colonies and the Cylons (figure 4). The false truce distracts the humans while Cylons attack, destroying all their planets and all but one of their military spacecrafts. The eponymous battlestar Galactica only survives because its commander, the skeptical Adama (Lorne Greene), doubted the Cylons’ intentions and the possibility for peace. Now Adama must lead his crew and the few civilian survivors on a caravan for “Earth,” a mythic thirteenth colony located “somewhere beyond the heavens.”

FIGURE 4. The Cylons of Battlestar Galactica (ABC, 1978–1979).

This premise promised lots of extraterrestrial excitement for newly minted Star Wars fans, but it also offered timely commentary on earthly affairs. Diplomacy was front-page news in the 1970s, as American experiments in “ping-pong” and citizen diplomacy contributed to a thaw in the Cold War. In April 1971, the US table tennis team became the first representatives of the United States to visit the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in over twenty years. Two months later, Mao Zedong (a ping-pong enthusiast) came to the United States as captain of the Chinese team. Soon thereafter President Richard Nixon became the first US president to visit the PRC since its founding in 1949. A few years later, Robert Fuller raised the public profile of citizen diplomacy by visiting the Soviet Union. Fuller was part of an international movement of private citizens contesting the continued hostilities between the United States and the Soviet Union through personal travel. Together, ping-pong and citizen diplomacy inspired new hope for a peaceful solution to the Cold War.12 In that context, the Cylons’ false truce in Battlestar Galactica represents more than just extraterrestrial treachery; it engages contemporaneous concerns about the power of diplomacy and cynically questions the wisdom of trusting longtime enemies. In many ways, the humans’ negotiations with the Cylons resembled recent thaws in the Cold War—making the Cylons’ duplicity that much more disturbing. Their betrayal justifies Adama’s rather hawkish insistence on active military vigilance, not to mention his scorn for pacifists like his president, whose faith in the Cylon armistice led to the destruction of the human colonies.

The show’s militarist commitments provided an inauspicious frame tale for the real-world truce that interrupted its premiere in the Eastern and Central time zones: the Camp David Accords. Unbeknownst to most of the world, US president Jimmy Carter had earlier that month invited Egyptian president Anwar el-Sadat and Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin to the presidential retreat in rural Maryland for a secret summit about their countries’ ongoing conflict.13 After thirty years, both sides had finally expressed interest in ending hostilities, but neither was willing to compromise publicly. Hence their private conference at Camp David, where Carter served as mediator and go-between for Sadat and Begin, who reportedly were not on speaking terms. After thirteen days, Begin and Sadat reached two partial agreements, or accords, leading to the Israel-Egypt Peace Treaty of 1979 and a shared Nobel Peace Prize.

ABC, NBC, and CBS all interrupted their Sunday evening broadcasts with live coverage of this historic diplomatic achievement. During the signing ceremony, Carter acknowledged that “there are still great difficulties that remain” but expressed “hope that the foresight and the wisdom that have made this session a success will guide these leaders and the leaders of all nations as they continue the progress toward peace.”14 Such hope might have seemed naive to Battlestar Galactica viewers, as the show’s Manichean universe primed them to question the power of the Accords. After all, the pilot begins with Adama’s warning to his president that long-term enemies can never trust one another. As he puts it, the Cylons “hate us with every fiber of their existence. We love freedom. We love independence—to feel, to question, to resist oppression. To them, it’s an alien way of existing they will never accept.” When the Cylons violate their truce, Adama’s cynicism seems prescient. Giving peace a chance only gives the enemy the upper hand. As Adama’s speech builds on real Cold War American exceptionalist rhetoric, the Cylons’ attack seems to justify that rhetoric via analogy. It also inadvertently promotes skepticism of Sadat and Begin’s momentous achievement.

The Camp David interruption has become a feature of Battlestar Galactica trivia collections, which is how I first learned about it. Some fans remember with pleasure ABC’s inadvertent juxtaposition of real-world and fantasy statecraft, but others recall only irritation. The younger the viewer at the time, the more likely they were to have been annoyed by the interruption. On multiple Battlestar Galactica and television fan forums, formerly juvenile viewers recollect how “at the end of hour two, ABC news broke in with the enfamous [sic] report” for approximately twenty minutes.15 Many were frustrated with the unplanned suspense and afraid that their parents would not let them stay up to watch the episode’s delayed conclusion. It was, after all, a school night. Blogger Bob R. recollects that he “FREAKED THE HELL OUT!!!” when ABC cut to the newsflash, while Jon Nichols, in a post to the blog Esoteric Synaptic Events entitled “You’re a jackass, Jimmy Carter,” asks sarcastically: “what did I get to see for a full hour? Not Richard Hatch as Apollo. Not Dirk Benedict as Starbuck. Not even that brat kid Boxey.” Instead he was “treated” to an unprecedented breakthrough in international relations, an offence, he satirically suggests, that may have led directly to the Egyptian president’s subsequent murder: “Wasn’t Anwar Sadat assassinated just a few years after signing those accords in the middle of Battlestar Galactica? Was an incensed Battlestar Galactica fan involved? Coincidence? I think not.”16

Then-adult Battlestar Galactica fans demonstrate more mature responses to the Accords interruption. Startrek.com writer David McDonnell appreciates the postmodernity of Battlestar Galactica’s historical coincidence: “Bizarrely, I recall ABC interrupting the story mid-premiere for breaking news coverage of the Middle East-Camp David Accords Signing (starring U.S. President Jimmy Carter with this episode’s special guest stars Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar el-Sadat). The juxtaposition of televised fiction and historical reality, of tomorrow’s space warfare and the promise of peace on Earth today was, well, jarringly surreal to say the least.”17 Journalist and blogger Steven Hart—who was a college student in 1978—now believes that “the announcement of the accords . . . was the most memorable thing about the show,” although he considers that to be the minority opinion: “Interesting, isn’t it, how the thirtieth anniversary of some crappy sci-fi TV show gets more attention than the thirtieth anniversary of the Camp David Accords?”18 Another viewer remembers watching the show at a comics convention and muses, “Looking back, I can only imagine that some who were against the peace accords must have tried to draw parallels between Israel and Egypt and the humans versus the Cylons who are about the sign a peace treaty . . . but that didn’t occur to me at the time.”19 In fact, there are no records of such cultural commentary at the time, yet the intersection of science fiction and world politics certainly emphasized the conservative ideology behind TV’s latest spectacle.

Viewer recollections may now be all that remain of the historical coincidence between Battlestar Galactica’s premiere and the signing of the Camp David Accords. There are no off-the-air recordings of “Saga of a Star World”—with or without the ABC newsflash that interrupted it—in any government, industry, or university archives. The Library of Congress possesses neither the newsflash nor the series. The UCLA Film & Television Archive and the Paley Center for Media have copies of the Battlestar Galactica broadcast master but not an off-the-air recording. The Vanderbilt Television News Archive only recorded regularly scheduled news programs on September 17, 1978, not news briefs, and the ABC News VideoSource likewise does not archive news break-ins.20 The Jimmy Carter Presidential Library does not keep recordings of network news coverage, only the White House Communication Agency logs (the master footage from which network news briefs are made).21 My inquiries to fans and on Battlestar Galactica message boards also failed to turn up a single off-the-air recording of the interrupted pilot in watchable condition. The few fans who have off-the-air recordings of “Saga of a Star World” edited their copies to eliminate ABC’s break-in. Only one claimed to own an off-the-air recording of the episode with news flash, and unfortunately, “it hasn’t held up well over the years.”22 Videotapes may be technologies of memory, as Sturken claims, but the technology is subject to elision and can also fail entirely. Like any material technology, it is vulnerable to the ravages of time, as are those who would use it to remember.

Off-the-air recording is thus a technology of co...

Table of contents

- Subvention

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Material Mediations

- 1. Collecting and Recollecting: Battlestar Galactica through Video’s Varied Technologies of Memory

- 2. The Commercial Economy of Film History: Or, Looking for Looking for Mr. Goodbar

- 3. “Let’s Movie”: How TCM Made a Lifestyle of Classic Film

- 4. Spirits of Cinema: Alcohol Service and the Future of Theatrical Exhibition

- 5. Blunt Spectatorship: Inebriated Poetics in Contemporary US Television

- 6. Shot in Black and White: The Racialized Reception of US Cinema Violence

- Conclusion: Expanding the Scene of the Screen

- Appendix: Documented Incidents of Cinema Violence in the United States through December 31, 2019

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index