![]()

1

A Modern Prometheus

Making his way to the podium at a high-level conference in Hong Kong in November 2018, He Jiankui is visibly nervous. An indignant murmur rises from the audience. A few seconds ago, the moderator called on listeners to ‘let him speak without interruption’ and to ‘remember we are here to listen to what he has to say’ – a very unusual request when a scientist is about to present his results.

The moderator, a prominent geneticist, also emphasizes that when the organizers booked He Jiankui many months previously, they had no idea what results he was going to present. As for He Jiankui himself, he is clearly proud of his achievement.1

‘If this were my child – if I were in the same situation – I would give this a try,’ he says later, during the Q&A session.

* * *

In 2018, 200 years after the publication of Frankenstein, Trinity College Dublin celebrated Halloween with a reading of the whole novel. At more or less the same time as Mary Shelley’s words were ringing out in the venerable university, twins ‘Lulu’ and ‘Nana’ – the first ever gene-edited babies – came into the world.2 This was not the first time scientists had intervened in the genetic material of unborn babies, but never before had anyone deliberately altered a specific gene.

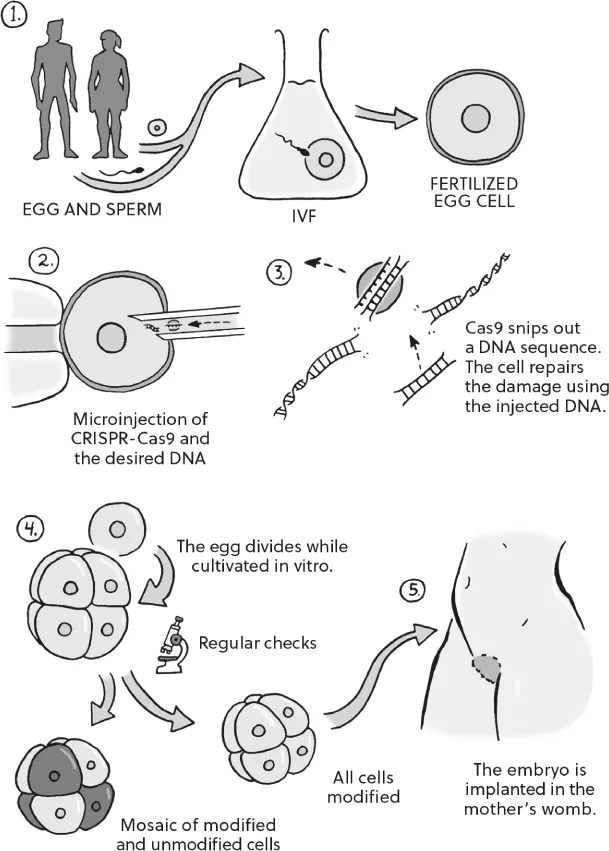

He Jiankui took eggs and sperm from a couple who wanted to become parents and performed conventional IVF. But before the fertilized eggs had begun to divide, he injected them with the ‘gene scissors’, CRISPR-Cas9, to alter a specific gene in their genetic material.

The gene that He Jiankui chose to alter, known as CCR5, is responsible for a tiny part of the immune system. Just like other genetic material, this gene sometimes undergoes a small change or mutation, and the new, mutant variant is passed on from parents to children. The result is that people carry different variants of the same gene or genes, depending on what they happen to have inherited from their parents. In most cases, tiny mutations of this kind make little difference; the genes function just as normal. Some mutations can cause problems that result in disease. But in certain rare cases, mutations can actually bring about a small improvement.

Some people have a mutant variant of CCR5 that seems to protect them against HIV. This variant is quite common in Europe, where about 10 per cent of the population have inherited it from one parent. However, to be protected against HIV you need to have inherited it from both your mother and your father, and that applies to only a very small percentage of people.3

Given that HIV has only been infecting people since the twentieth century, this mutation of CCR5 can’t have become widespread just because it protects against that specific virus. It’s been speculated that it may also have provided protection against other diseases in the course of history, such as bubonic plague or smallpox. However, some studies suggest that people who have inherited this particular mutation are also at greater risk of contracting other illnesses, such as West Nile fever and flu. The international scientific community doesn’t yet know quite how it affects the body, apart from reducing the risk of an HIV infection.

Though we humans have been gene-editing animals for some decades now, there has been a near-total consensus among scientists that we shouldn’t interfere with human embryos that are going to be brought to term. To grasp why this is so much more revolutionary than other gene technologies, we need to understand a basic issue: there are different categories of cell.

* * *

The human body contains over 37,000 billion cells, ranging from the specialized light-sensitive receptors in our eyes to the rectal muscles that move what remains of the food we’ve consumed to its final destination.4 But gene technology distinguishes just two types: somatic cells and embryonic cells.

Nearly all cells are somatic. The word comes from the Greek soma, meaning body. Somatic cells belong to us alone, as individuals: our children don’t inherit cells from our nose or heart. That means that the risks associated with applying gene technology to cure a tumour, correct a failing eye or support a damaged liver always come down to the danger of harming the individual patient. While such risks may be considerable, they are always weighed up against the pain and the difficulties the patient suffers as a result of the disease which the medical practitioner is trying to cure. They are the same risks that proved so devastating for Jesse Gelsinger – tragic in their effect, but confined to a single person.

However, there are major existential issues at stake if, like He Jiankui, you alter embryonic cells: eggs, sperm and the very first cells that form once an egg has accepted a sperm and begun to divide. At this stage, interventions that modify genetic material can have a huge impact. They may cure terrible genetic diseases, or, possibly, reduce the future child’s risk of succumbing to everything from Alzheimer’s to heart attacks. However, editing embryonic cells has two major consequences. First, the genetic modification will be present in every cell of the body into which the embryo develops. The change effected by He Jiankui will be with ‘Lulu’ and ‘Nana’ all their lives, from birth to adulthood to menopause, and in old age.

Second, the edited genes will be passed on to the next generation. A gene-edited child who becomes a grandmother can pass on the altered gene to her grandchildren and their grandchildren’s children. There is a chance – and a risk – of changing the whole future of humankind. That was why the audience murmured and the cameras flashed when He Jiankui announced the girls’ birth.

* * *

He Jiankui had contacted an organization supporting people living with HIV in China, BaiHuaLin, to request help with finding couples consisting of a would-be father with HIV and an uninfected would-be mother. The aim was to protect any future offspring from being accidentally infected by their father in daily life, and from the discrimination and stigma suffered by many people with HIV in China. So he was looking specifically for couples in which the would-be father felt vulnerable and discriminated against because of his infection. To protect an embryo against HIV infection from a father with the virus, the sperm of the father-to-be are ‘washed’ before insemination to rid them of the virus. He Jiankui also followed this procedure. Three couples decided to take part in the experiment, though one pair later withdrew.5

The parents-to-be had a choice between modified embryos, in which He Jiankui had attempted to edit the CCR5 gene, and unmodified ones. Both couples opted for gene-edited embryos. By the time He Jiankui spoke at the conference, the second woman was pregnant with a gene-edited baby, who was presumably born in 2019. The reason the child’s fate remains unknown will soon become clear.

When He Jiankui announced his results, it turned out that he hadn’t succeeded in creating the precise variant of CCR5 that scientists know protects against HIV. Rather, he had produced new mutations which may – or may not – have the same effect. In the case of one of the twins nearly everything went as planned, so that the same mutation is to be found in all the child’s cells, at least in theory. With the other, however, something happened that’s common when humans try to gene-edit animals: some cells were changed, but not all of them. Presumably that was because the egg had already started to divide before He Jiankui edited the gene. As a result, the child’s body is now a mosaic of modified and unmodified cells. It isn’t clear whether this will protect her against HIV, or whether it will have any other effects in the course of her life.6 He Jiankui has been criticized for failing to halt the experiment when he saw that the wrong mutation had taken place and that not all the cells had been altered.

There’s also a risk that the CRISPR ‘scissors’ may have cut genetic material in several places, modifying some other gene in the girls’ bodies. It’s incredibly hard to identify tiny changes in genetic material. He Jiankui claims to have searched for unintended modifications without finding any, but it’s impossible to be sure.

There are no international laws to prevent scientists (or countries) from gene-editing embryos. The 1997 Oviedo Convention, signed by 30 countries, bans inheritable genetic modifications, but countries such as the UK haven’t signed it, claiming that it is too restrictive.7 Conversely, Germany has refrained from signing because it regards the convention as too permissive.

So views on gene-editing vary, and the stance of each individual country is a matter of national law. However, in 2015 some of the world’s leading geneticists took the initiative of reaching a kind of gentleman’s agreement. The gist of it was that they would edit embryonic genes only in the context of basic research to deepen understanding of diseases and foetal development. Thus only embryos that would never develop into babies could be modified. The scientists concerned decided that experimental gene-editing of foetuses that would be brought to term was irresponsible until the safety issues had been resolved, and until there was broad societal acceptance of such experiments, and the scientific community could participate in an open process. These were idealistic but reasonable aims. For the time being, the watchword was ‘No tweaking!’8

If the truth be told, the conference in late 2015, when the guidelines were drawn up, was a hastily arranged affair. The new gene technology was still a novelty. Although it had always been clear that the method could be used on human embryos, most of the scientists assessing the situation thought that stage was a fairly long way off. This was partly because of existing legislation, but largely because science sometimes develops at a very uneven pace.

But this time things moved ultra-fast. Immediately after the publication in 2012 of the first studies showing the workings of CRISPR, the ‘gene scissors’, scientists in China began to try gene-editing human embryos. The first scientific article to show that this was possible appeared as early as spring 2015.9 The study in question was the work of Chinese scientists, who had tried to edit a gene responsible for thalassaemia, a hereditary blood disorder common in South East Asia and the Mediterranean region. This experiment was sufficiently impressive, and aroused sufficient concern, to push the scientific conference mentioned above into drawing up guidelines the very same year. Since then, quite a few scientific papers on modified human embryos have been published. After the first few that came out between 2015 and 2018, they have been appearing with increasing frequency. Soon after the first results emerged, scientists in countries including the United States, the UK and Sweden began applying CRISPR to embryos to clarify certain scientific issues. However, most results have come from China, where the technique has been further developed and a number of problems resolved – though application has been restricted to basic research, without any children being born as a result. Up till now.

* * *

Beijing’s Forbidden City lies in a hutong district, an extensive area of one-storey dwellings built around small inner courtyards, forming an intricate system of alleys and narrow streets. Parts of this quarter date back to the fourteenth century. Despite the scale of rebuilding and social change, some of the most central hutongs remain as they were, and they teem with life. People sit at tables playing games, others lounge in courtyard doorways, smoking or keeping an eye on children at play. Strolling through the alleys gives one a sense of timelessness in a city that’s 3,000 years old. I am here to investigate how far Chinese scientists have advanced with the very latest developments in gene technology.

Any genetic modification of the embryo must take place before the fertilized egg starts to divide. Scientists inject CRISPR-Cas9 into the cell, where the CRISPR system can cut out or edit chunks of genetic material. By the time the egg starts to divide, all its cells will have been modified. However, occasionally something goes wrong, resulting in an embryo that is a patchwork of modified and unmodified cells.

If you walk eastwards from the Forbidden City and stroll through the picturesque hutongs for a good half-hour, you’ll reach a newly built shopping centre, cheek by jowl with the old quarters of town. It looks as if a highly sophisticated spaceship has landed in the city, a vessel built by wealthy extraterrestrials with a finely developed sense of the aesthetic. Huge oval beehives of white concrete and dark glass are linked together by gently curving footbridges, illuminated fountains and sculptures. These edifices, teeming with stores and boutiques, are a magnet for families on shopping trips. This centre provides a glimpse of the new China, a country that makes a European wonder whether she’s accidentally time-travelled into the future. In a Starbucks cafe inside the shopping centre, I meet Tang Lichun, one of the first scientists to succeed in modifying a human embryo in a laboratory.

‘We began this project as early as 2014, very early. And in the beginning we had many difficulties; it didn’t work on the embryos. […] We tried and we tried […] and got results. It was very exciting,’ says a beaming Tang Lichun when I ask him to tell me about the experiment.10

The technical problems he and his colleagues encountered meant they weren’t the very first to demonstrate that the new technology could be used to gene-edit human embryos. But they were the first to show that it can also be applied to healthy embryos – embryos that could develop into babies – although Tang...