![]()

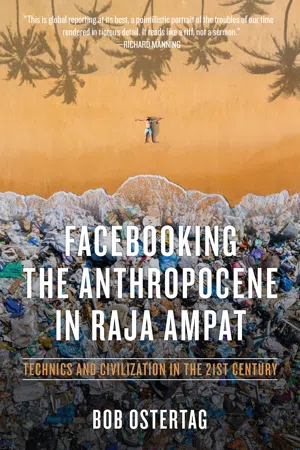

Facebooking the Anthropocene in Raja Ampat

Notes on a One-Year Concert Tour

Dear Friends,

Forgive me for being such a poor correspondent during my year around the world. The daily kaleidoscope was so relentlessly compelling I found it difficult to collect my thoughts, much less write them down.

At the end of it all I have arrived in Berlin, an island of sanity in a crazy world.

More precisely, I am in the naked gay sunbathing section of the Tiergarten, Berlin’s large city park. Green grass, green trees, blue sky, a lovely blanket of calm everywhere, lots of naked men lying in the sun. Families with little kids walking by. The easy mixing of naked gay men and kids on their way to get ice cream bothers no one.

Beautiful Berlin.

The only men not lying motionless are me and two others just to my left. One of these is in a motorized wheelchair. He has a disorder that makes it impossible for him to control his movement and is flailing around in the chair. The other man is the flailing man’s caretaker, who is spoon-feeding the one in the chair. The man in the chair is naked. His caretaker, clothed, has brought him here so he can be naked in the park with the rest of the guys.

The condition of the man in the chair is so severe that it is hard for him to swallow, and the quiet tranquility of the park is periodically broken by his loud and urgent choking when the food goes does the wrong way.

I am doing yoga.

Perfect.

At last I can think.

Love,

Bob

The first thing that jumps out at you while traveling the world today is that the world you are moving through is coming apart. Or rather, there is one world—the old world—coming apart, and a new world is coming into view.

I have seen this with my own eyes, laid out in front of me like a buffet, yet I must almost certainly be wrong. The end of the world has, after all, been described over and over through the millennia by honest and well-meaning people who were certain they were witnessing it and who convinced many others to believe the same.

William Miller, for example, did a particularly deep dive into Bible numerology, and concluded that the world would end “sometime between March 21, 1843, and March 21, 1844.” The message spread first through a periodical out of Boston called Signs of the Times, then by a Millerite movement. By the time the moment for the end of the world arrived, the movement claimed to have distributed five million copies of Millerite periodicals, and there were avowed Millerites in Canada, England, Norway, Chile and the Sandwich Islands (now Hawaii). When March 21, 1844 passed uneventfully, Millerite numerologists redid their math, found the mistake (it was in the 2,300-day prophecy in Daniel 8:14) and proved that the world would end on “the tenth day of the seventh month of the present year, 1844,” which worked out to be October 22. When the day came and went, what followed became known as “The Great Disappointment.” Stunned Millerites confronted not just their own confusion, but church burnings, mob violence, and constant ridicule.

So no one should be dumb enough these days to declare that the world is ending. Yet, even as the naked man in the wheelchair was choking on his food, the world’s preeminent geologists were, in fact, announcing the end of the old world and the beginning of the new, in the form of a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene: a world in which the consequences of human activity have reached geological proportions.

More precisely, the Anthropocene Working Group, of the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy, voted to recommend that the International Commission on Stratigraphy declare the Anthropocene a new geological epoch.

Human activity, they declared, now affects natural global systems and processes so profoundly as to leave its mark in the stratigraphic record. Martian stratigraphers arriving on earth millions of years in the future to study the chemical composition of layers of rock would learn that vast and unprecedented planetary changes suddenly began occurring right about now.

Geologists spend a lot of effort sorting out when one geological epoch ends and a new one begins. They have agreed on dividing lines for geological eras going back 545 million years: the Pleistocene, the Pliocene, the Miocene, and so on. Each of these geological epochs lasted for millions of years. The most recent epoch, the Holocene, began just eleven thousand years ago. By the timescale of all other geological epochs, the Holocene was a newborn. So to declare that the Holocene has already given way to the Anthropocene is to declare that something has occurred (a geological era has lasted just ten thousand years) that has no precedent on earth in the last five hundred million years: Earth 2.0.

Geologists are a pretty staid and stable bunch. They arrived at this utterly preposterous conclusion by analyzing the chemical composition of things like glacial ice cores, layers of rocks, and sediment at the bottom of lakes. But nongeologists without chemistry labs can still see the processes of the Anthropocene at work. All we have to do is hop on an airplane and go look around.

Incidentally, airplane travel is one of the most effective ways an individual can contribute to the processes of the Anthropocene. The only behavior a single person can engage in that leaves a bigger carbon footprint than airplane travel is eating beef.

I left my home in San Francisco in March 2015. California was in the midst of a historic drought. Lakes were drying up and forests were burning. The biggest forest fires in history. Just before I left, the crab fishing season along the entire coastline of California was cancelled because the unusually warm waters in the Pacific had turned the crab toxic. As I was coming home a year later, research confirmed that the largest coral “bleaching event” ever was underway in that same Pacific Ocean.1

I arrived in Europe for the historic European heat wave of 2015. Temperatures topped 100 degrees Fahrenheit in northern Germany. I left Europe for Lebanon, where one in five people living within the nation’s borders is a refugee from neighboring countries racked by historic droughts.

In El Salvador I attended a water management class for campesinos from villages with no more water. Their water now arrives by truck. Central America was in its worst drought on record. The corn harvest failed for many Salvadoran subsistence farmers for the first time in anyone’s life. The purpose of the class was to search for new water management methods that would allow subsistence farming to continue in areas where the only water available arrives by truck.

How can you have subsistence farming if the only water arrives by truck?

I visited my friend Myrna at her beach house outside of San Salvador, the capital city. The house formerly opened onto a beautiful sandy beach, but a few months before my arrival the area experienced what was being called a “tidal event.” One day the high tide rose higher than it ever had or was predicted to, leaving both the beach houses of the comparatively well off, and the crude wooden shops of their poorer neighbors, standing in saltwater. Not nearly as dramatic as a tsunami. The water arrived on a tide instead of a wave. Nevertheless, the “event” covered the land with salt water and the beach with rocks. The salt killed the trees, while the rock now completely blankets the beach. Not the tiny sort of rocks that generally cover rocky beaches but boulders of all shapes and sizes. Boulders strewn about everywhere, one on top of another on top of another.

For the army colonel who owns the only big modern hotel on the beach and has strings to pull and money to spend, there is no problem. If he can marshal the resources to move the rocks off his property, he will have the only beach around. Otherwise, he can take his money and his connections elsewhere. For middle-class Myrna, the rocks mean that the beautiful beach she came here for is gone. Not a happy turn of events, but she will survive. It is her beach house, not her home. But for all the shopkeepers who had invested what little they had in the ramshackle wooden shops that lined the beach, it is the end of their livelihoods, and they live in a very poor country where alternative livelihoods are hard to come by.

On the scale of the consequences of the transition from the Holocene to the Anthropocene, the “tidal event” on El Salvador’s coast is no big deal. Tinier than tiny. Not even anything. Yet there, where the beach used to be, sit tons and tons of rock and the abandoned shacks left behind by their proprietors, along with all their hopes and dreams.

What will the displaced shopkeepers from the beach do? Or the campesinos from the mountain villages which have run dry? The best option may be to flee, and begin the long and dangerous journey to the US, where they will be viewed as “illegal immigrants,” not “climate refugees.”

Prediction: in the near future, a new political drama will emerge over who gets to be a “climate refugee.” Until now, the big political drama of human migration has been about who counts as a “political refugee” fleeing political oppression, as opposed to those fleeing economic hardship, who get stuck being “immigrants.” As if economic hardship and political oppression could be so neatly disentangled. Was the economic hardship the cause or the result of the political repression? International NGOs, United Nations officials, and academics have actually been trying to develop criteria to answer that question. But in practice the distinction is made not by reasoned argument but by political power and advantage. In the US, people who flee regimes that are not friendly with the US are “refugees,” while those fleeing friendly regimes are “immigrants.” “Refugees” are sometimes welcomed because they demonstrate the superiority of our political system. “Immigrants” are tolerated up to a point as long as they clean our toilets, pick our crops, care for the children we are too busy to care for ourselves, and don’t bother anybody. With Donald Trump in the White House, the status of immigrants is being profoundly contested. Though neither Trump nor his supporters have explained who will clean their toilets or their children if all the undocumented immigrants are deported.

A third character will soon be added to this drama: the “climate refugee.” There will be a lot of potential candidates, for climate change will create migration on a scale never known. But how will we distinguish the cause of their hardship in a world where poverty and war were endemic even before climate change came along?

The exodus has already begun. Nearly all of those risking everything to get into Europe today are from drought-stricken areas. Those areas from which they fled are, in turn, full of even more desperate people who fled even more severe droughts. Get ready for protests and demonstrations, slogans on banners, angry denunciations, and streets full of riot police and tear gas—all about who gets to be declared a “climate refugee.” Coming soon to a screen near you. Hint: subsistence farmers from drought-afflicted areas in Central America and North Africa are not likely to make the cut; oil billionaires from the Persian Gulf, an area which is predicted to be too hot for human life by the end of the century, are a better bet.2

I went from El Salvador to Detroit and landed in yet another water crisis. But Detroit was an outlier among the world’s water crises, because its water crisis was entirely the creation of policy. There was no drought or tsunami or even tidal event. To the contrary, Detroit lies at the edge of the Great Lakes system, which contains 21 percent of the world’s surface freshwater, suggesting this might be a good place to seek shelter from climate catastrophe. Yet many of Detroit’s poorest residents were without water due solely to government policy.

At the peak of American industrial power in 1960, Detroit had a population of 1.7 million. When I arrived less than half that number remained. The jobs had migrated to southern states where unions were not a problem, or to other countries. Many whites had migrated to the burbs. The process had been going on for so long that much of the debris from the collapse had been carted away. You drive through entire neighborhoods of empty blocks with absolutely nothing on them, the flat and barren landscape more reminiscent of an Iowa cornfield in winter than a city. You could farm that land if you wanted to, and some committed urban farming collectives were doing so. You just couldn’t plant anything in the dirt, which is contaminated with lead. You have to truck in clean dirt.

Detroit declared bankruptcy in 2013, the largest American city in history to do so. An “emergency financial manager” was appointed by the Republican governor of Michigan and tasked with somehow squeezing enough blood from the stone that is Detroit to pay off the city’s creditors. He decided one way to go about this was to collect outstanding water bills, by shutting off the water to those who owed more than $150.

Figuring out who in Detroit owes more than $150 on their water bill is not as simple as it might sound. The Detroit water system was built for a population heading toward two million but serves less than one million. The fixed costs of the giant system are now divided among less than one million users, making for water bills nearly double the national average in one of the poorest cities in the country. And then there are all the leaks and breakages from the wreckage of the old system. One person was presented a water bill of $10,000.

City-owned golf courses, however, owed more than $400,000 but were under no threat. Same for the professional hockey and football arenas ($137,000). Collecting just these three bills would have raised as much money as shutting off the water to 3,500 people.

You can live in the dark, and you can live cold. You can live hungry, but you cannot live without water. You cannot even go a full day without water.

If there is no water in your house, the state can take your children away. Thousands of people were put at just that risk, to raise the same money that could have been raised collecting three bills from sports facilities.

The United Nations sent a special representative to Detroit to inform the city leaders that access to water is a basic human right, and that the city’s water policy violated international human rights law. The dumbfounded authorities replied that this was the United States, and no one in the world tells Americans what to do, and weren’t UN representatives supposed to be in some other country where there were real human rights issues?

The problem goes beyond water. All the utilities are a mess. Over the years during which over a million people left, properties were abandoned, occupied, stripped for parts, and occupied again. In many areas only the poorest of the poor, the ones who simply had nowhere to go, remained. They lived where they could. Just figuring out who owns a house can be vexing. There are many people paying rent to someone who claims to be their...