eBook - ePub

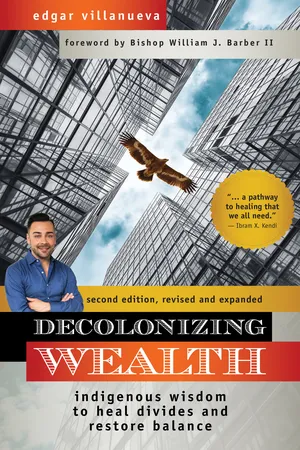

Decolonizing Wealth, Second Edition

Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Decolonizing Wealth, Second Edition

Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance

About this book

This second edition expands the provocative analysis of the racist colonial dynamics at play in philanthropy and finance into other sectors and offers practical advice on how anyone can be a healer. The world is out of balance. With increasing frequency, we are presented with the inescapable truth that systemic racism and colonial structures are foundational principles to our economies. The $1 trillion philanthropic industry is one example of a system that mirrors oppressive colonial behavior. It's an industry whose name means "the love for humankind," yet it does more harm than good. In Decolonizing Wealth, Edgar Villanueva looks past philanthropy's glamorous, altruistic façade and into its shadows: white supremacy, savior complexes, and internalized oppression. Across history and to the present day, the accumulation of wealth is steeped in trauma. How can we shift philanthropy toward social reconciliation and healing if the cornerstones are exploitation, extraction, and control? Drawing from Native traditions, Villanueva empowers individuals and institutions to begin to repair the damage through his Seven Steps to Healing. In this second edition, Villanueva adds inspiring examples of people using their resources to decolonize entertainment, museums, libraries, land ownership, and much more. Everyone can be a healer and a leader in restoring balance—and we need everyone to do their part. As Villanueva writes, "All our suffering is mutual. All our healing is mutual. All our thriving is mutual." Are you ready?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Decolonizing Wealth, Second Edition by Edgar Villanueva in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Berrett-Koehler PublishersYear

2024eBook ISBN

9781523091430

PART ONE

Where It Hurts

It is true that the first part of this book consists of mostly dark, painful stories, stories of what people endure to gain access to money, stories of the twisted things people do once they have access to money and the power it confers. My own journey through the world of philanthropy forms the backbone, leading to observations about wealth, the colonizer virus, and trauma. Some may say it’s tiresome to dwell on the hurt—after all, there’s a relentless (if artificial) drive to “Stay positive!” in America, to focus only on solutions. Yet an essential step in the process of decolonization is hearing out the painful stories of the colonized and the exploited, respectfully and with an open heart.

The chapters in part 1 are named for elements in a slave plantation. As token people of color working within the field of philanthropy, one of our regular watercooler conversations over the years, held in hushed voices, revolves around the analogy of a plantation. Those seeking funding are the people with the least power—the field hands, begging for scraps, given no dignity and treated with no respect. One step up, people of color working in philanthropy, are the house slaves, because we get to be close to the power and the privilege. We benefit from our position in all kinds of ways. Different enslaved people behave differently once they get inside the master’s house. Some help those who are still out in the fields. But others take on the characteristics of the master and lord it over those less fortunate. They do whatever it takes to keep their own lucky position intact and unthreatened. Then there are the overseers, usually a white man, but occasionally an enslaved person promoted to the position. Granted, they are in a tough position, under pressure from the master to squeeze as much profit from the slaves as possible, but they are infamous for indifference, delusions of grandeur, and, at worst, cruelty. The overseer in a foundation might be its CEO or executive director.

The plantation metaphor implicitly raises the question of the “master’s tools,” a reference to the poet and civil rights activist Audre Lorde’s declaration, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”1 In other words, given the level of trauma caused by the colonizer virus and wealth consolidation, can funders actually support transformational change? The master’s tools, as I view them, are not money; the tools are anything corrupted to serve the aims of exploitation and domination. If money is an inherently neutral force, as I described in the introduction, then it can also be used for good, as medicine, as I will explore in part 2.

There is a folktale about a serpent that once upon a time was plaguing a village. The serpent had devoured many of the villagers, including children, and everyone lived in fear of its next attack. A flute player who was still among the living decided something must be done. He packed a bundle of food and a knife, and he went to the edge of the village and began playing his flute. As he expected, the music drew the serpent to him, and in one bite the serpent swallowed the flute player. It was dark inside the serpent’s stomach, but the flute player pulled out his knife and cut away a little of the serpent’s stomach and ate it. Bit by bit, he cut away the serpent’s flesh from the inside. This went on for some time, until finally the flute player reached the serpent’s heart. When he cut it out, the serpent died, and the flute player crawled out of the serpent and returned to the village, bringing along the serpent’s heart to show everyone, so they would know they no longer had reason to be afraid.

I see this as a story about grappling with collective trauma. We have to enter into the darkness of it. It can’t be dealt with from the outside. We have to go inside, despite our resistance, and allow ourselves to feel swallowed up and surrounded by it. It might seem like the pain will never end and there is no way out of it, but bit by bit we come to the heart of the matter. The flute player had prepared himself for a prolonged reckoning. Some kinds of grappling, for especially deep wounds, are lifelong projects. If we do not reckon with it, however, if we carry around unresolved grief, we will spend our lives plagued by the serpent. When we finally get to the heart of the matter, we can emerge lighter and ready to build something new.

CHAPTER ONE

Stolen and Sold

How notions of separation and race resulted in colonization and trauma

Who’s your people? That’s the first question Lumbee Indians ask when we meet someone new, as if we’re working out a massive imaginary family tree for humanity in our heads and need to place you on the appropriate limb, branch, or twig. We even sell a T-shirt that has that printed on it: “Who’s your people?”

I throw people off with my Latino-sounding last name, which came from my nonbiological father, who was in fact Filipino. He was in my mom’s life, and therefore in my life, for a brief moment between the ages of zero and two. When I’m with other Lumbees, I have to mention the last names of my grandfather and grandmother, Jacobs and Bryant, so they know where to place me in the Lumbee family tree. A Lumbee will keep an ear out for our most common surnames, like Brooks, Chavis, Lowry, Locklear. As soon as you say you’re related to these families, the stories unfold: I knew your great-grandfather. I knew your auntie. There’s always a connection.

If you’ve never met a Native American in person before, you might be saddled with some common misconceptions about me. I have never lived in a teepee. I’ve never even lived on a reservation. I can’t survive in the wilderness on my own. I can’t kill or skin a deer. Shoot, I can’t even build a fire. No, I didn’t get a free education (still paying off those loans!), and yes, I pay taxes.

It wasn’t until my late twenties that I really began the process of deeply connecting with my Native heritage. There were three main reasons for this: One, I’m an urban Indian. At least half to three-quarters of us are. Note, “urban” doesn’t necessarily mean we live in cities; it’s a term that refers to all Indians who do not live on reservations. And yes, I use the terms “Native American” and “(American) Indian” interchangeably. Unless you’re an Indian too, you’re probably better off sticking with “Native American,” just to keep things simple.

Two: I’ve spent the majority of my adult life working in philanthropy, basically the whitest, most elite sector ever.

Three: I’m Lumbee.

The people known today as Lumbee are the survivors of several tribes who lived along the coast of what is now North Carolina. Those ancestors were the first point of contact for the Europeans, in the late 1500s. So we have had nearly 500 years of interaction with the settlers. Contrast this with some of the West Coast tribes, for many of whom the experience of colonization has been going on for just 200-some years, less than half the time. My people have been penetrated by and exposed to whiteness for a long, long time—longer than any other North American Native community. We assimilated to survive. The fact that any shred of anything remotely appearing to be Native exists among us is really a miracle. “Resilience” has become a trendy word in conversations about business, insurance, and climate. Let me tell you, my people really have a corner on resilience.

Originally Sioux-, Algonquin-, and Iroquois-speaking people, today Lumbees have no language to call our own, although we have a distinctive dialect on top of the southern North Carolina accent. We have so fully embraced Christianity that when you go to apply for or renew your tribal membership card, you are asked which church you attend. While we maintain our notion of tribal sovereignty, we are pretty thoroughly colonized.

There are people who deny that Lumbees are Native at all, as if a group of opportunists just came together to make this tribe up because they wanted to get some government money. Honestly, that’s ridiculous. All you have to do is go to Robeson County, North Carolina, where there are 60,000 people concentrated who definitely are not quite white or Black. Some of them look as stereotypically Indian as Sitting Bull, as my maternal grandfather did. Lumbee physical characteristics are on a spectrum from presenting white to presenting Black, because the area historically has been a third, a third, a third—Lumbee, Black, and white—and there has been some intermingling over the last half millennium. In fact, the most probable fate of the famous Lost Colony of Roanoke—the group of English settlers led by Sir Walter Raleigh who arrived in 1584—is that they didn’t disappear at all. They just got hungry and needed help, and the Native coastal Indians, my ancestors, took them in and integrated them. There have been linguistic studies on the British influences within the Lumbee dialect that further support that theory.1

Other Native tribes give Lumbees a hard time because of anti-Black racism. Indians elsewhere in the country have said things to me like, “Oh, you guys are not really Indian. You play hip-hop at your powwows” (which is not true!). Or they’ve said we’re not Indian because we’re not fully recognized by the federal government. There’s such a scarcity mentality—part of the legacy of the colonizers’ competitive mindset—that there are Indians who fear there will be fewer federal resources paid out to them if more unrecognized Indians receive federal recognition.

It was only in 1956 that the U.S. Congress recognized Lumbees as Indians by passing the Lumbee Act, but the full benefits of federal recognition were not ensured in the act, and to this day we are still fighting for the federal legislation that would do so. In 2020, legislation that would grant Lumbees full federal recognition passed the House of Representatives but failed to receive approval from the Senate.2 There are eight tribes in North Carolina, and only one, the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Nation, is federally recognized. Any of us could be unrecognized tomorrow. Federal recognition is given and taken away by the stroke of a pen. There have been tribes who were granted federal recognition by one administration, until the next president who came in took it away—this happened to the Duwamish Tribe in Seattle.3 We’re all subject to someone who is not an Indian himself (it’s usually a him) calling those shots.

When I was a child growing up in Raleigh, North Carolina, in the 1980s, official forms had boxes for “White,” “Black,” and “Other.” Until the migration of Latinos into the state in the 1990s, and later the Asians who came when Research Triangle Park really took off, Natives were usually the only people in the Other box. I always had to check the Other box. For the most part, that was the extent of my Native identity, because no one was stirring up Native pride or celebrating Lumbee heritage in my school. My family was more focused on survival.

Being Native American inherently involves an identity crisis. We’re the only race or ethnicity that is only acknowledged if the government says we are. Here we are, we exist, but we still have to prove it. Anyone else can say they are what they are. No one has to prove that they’re Black or prove that they’re Latino. There are deep implications to this. The rates of alcoholism, substance abuse, and suicide are linked to this fundamental questioning of our identity. We exist in the Other box. To try to feel safe inside that box, and then be told you’ve got to prove your right to be in that box, that the box itself is under threat, is deeply demoralizing.

My identity as a Native American is complicated. It’s been a long journey to decolonize myself and connect more deeply with my Indigenous heritage. Still, it’s the bedrock foundation of my identity. If I were a tree, my Native identity would be my core, the very first ring.

Unpacking Colonization

Colonization seems totally normal because the history books are full of it—and because to this day many colonizing powers talk about colonization not with shame but with pride in their accomplishments. It’s so strange. Conquering is one thing: you travel to another place and take its resources, kill the people who get in your way, and then go home with your spoils. But in colonization, you stick around, occupy the land, and force the existing Indigenous people to become you. It’s like a zombie invasion; colonizers insist on taking over the bodies, minds, and souls of the colonized.

Who came up with this, and why?

Without going too deep into the details of humanity’s evolution (there are other great books for that),4 I just say that the concept of colonization followed the trend that seems to have begun when humans first became farmers and began managing, controlling, and “owning” other forms of life—plant and animal (giving us this horrifying word, “livestock”). Conceptually, this required that humans think of themselves as separate from the rest of the natural world.

This was the beginning of a divergence from the Indigenous worldview, which fundamentally seeks not to own or control but to coexist with and steward the land and nonhuman forms of life. As the philosopher Derek Rasmussen put it, “What makes a people Indigenous? Indigenous people believe they belong to the land, and non-Indigenous people believe the land belongs to them.”5 It’s not that Indigenous people were or are without strife or violence, but their fundamental worldview emphasizes connection, reciprocity, a circular dynamic.

It’s important to remember that a worldview is a human creation. It’s not our destiny. It’s not inevitable. Even though it came close to disappearing entirely as the separation worldview took hold and became dominant over several centuries, the Indigenous worldview persisted.

The separation worldview, on an individual level but also at every level of complexity, goes like this:

The boundaries of my body separate me from the rest of the universe. I’m on my own against the world. This terrifies me, and so I try to control everything outside myself, also known as the Other. I fear the Other; I must compete with the Other in order to meet my needs. I always need to act in my self-interest, and I blame the Other for everything that goes wrong.

Separation correlates with fear, scarcity, and blame, all of which arise when we think we’re not together in this thing called life. In the separation worldview, humans are divided from and set above nature, mind is separated from and elevated above body, and some humans are considered distinct from and valued above others—us versus them—as opposed to seeing ourselves as part of a greater whole.

This fundamentally divisive mindset led to an endless number of categories by which to further divide up the world and then rank them, assigning to one side the lower rank, the lesser power. So the rational took its place and lorded over the emotional, male over female, expert over amateur, and so on. In every sector, the very structure and approach of organizations also reflected a divisive, pigeonholing, and ranking mindset.

The separation-based economy exploits natural resources and most of the planet’s inhabitants for the profit of a few. It considers the earth an object, separate from us, with its resources existing solely for human use, rather than understanding the earth as a living biosphere of which we are just one part. Money, of course, has been used and is still constantly used to separate people—most fundamentally, into Haves and Have-Nots.

Separation-based political systems create arbitrary nation-states with imagin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword by Bishop William J. Barber II

- Introduction: What if Money Could Heal Us

- Part One: Where It Hurts

- Part Two: Being a Healer

- Part Three: How to Heal

- Conclusion: Coming Full Circle

- Notes

- Glossary of New Terms

- Discussion Guide and Resources

- Acknowledgments

- Index

- About the Author