![]()

1

THE LEGACY OF CENTURIES

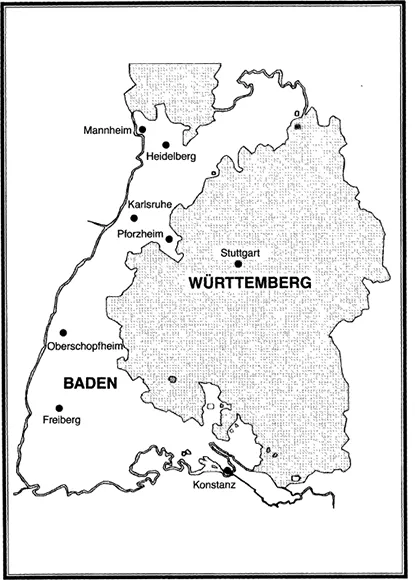

BEFORE THE UNIFICATION of Germany in 1871 Baden was an independent grand duchy in southwest Germany. Its name derives from the many sulfur-bearing hot springs that exist in the area and from the fertile plowlands thereabout. Baden province is shaped somewhat like a human leg wearing a fifteenth-century Burgundian shoe. It is bounded on the west and south by the Rhine river and on the north by the Main. Eastward it extends irregularly into the Black Forest, to Hesse and Wuerttemberg. Baden is 138 miles from north to south, about sixty miles from east to west at its southern extremity, and from fifteen to thirty miles wide farther north.

The mountains of the Black Forest cover most of Baden, but the richest area is a strip of land five to fifteen miles wide along the east bank of the Rhine facing France. This “Garden of Germany” has long seemed particularly favored by nature. It has the most fertile soil in Germany and a climate that, though capricious, is so mild that finches stay over the winter there. Nearby streams running out of the hills provide abundant water for people and animals and make it possible to grow a variety of grains, vegetables, and fruits—even grapes. The hills themselves provide ample wood for fuel and sandstone for building. A large marsh supplies great quantities of reeds and “sea grass,” materials useful for making baskets, stuffing mattresses, and other household purposes. Looking down from the hills into this valley in springtime one can see lush green meadows and countless blossoming fruit trees. Most of the population of Baden has lived and continues to live within this area.

Midway up this valley lies Gau Ortenau, in which Lahr county is situated. Originally established by the Franks, Gau Ortenau formerly looked a few miles northwestward across the Rhine to Strasbourg as its commercial, cultural, and religious center. Lahr county contained forty-three communities, one of which is Oberschopfheim, a farm village situated in a “kettle” between hillsides seven miles east of the Rhine at the base of the foothills of the Black Forest. In 1929 the property boundaries of Oberschopfheim stretched from the Schutter river in the valley to the mountains three miles eastward. It comprised 2,562 acres, with the village in the center.

Little is known of the pre-Roman history of Lahr county. The Romans reached the area in the first century A.D. They brought with them grapevines and fruit trees of good quality that have been a source of livelihood to the present day. About 100 A.D. the emperor Trajan built a major highway from Basel northward to Mainz. For centuries thereafter it was the main artery of north-south transportation along the upper Rhine. Unfortunately, it was also an easy, obvious route for invaders of this rich, low, level valley. For the next eighteen centuries this locale was one of the most fought-over and pillaged sectors of Europe.

Throughout the Middle Ages churchmen and nobles attempted to increase their control over peasants, the latter to resist and reverse this process. From the late sixteenth century to the early nineteenth century fortune favored the peasants. All over southwest Germany compulsory labor and feudal dues were gradually transformed into simple rent payments. Nonetheless, the history of Oberschopfheim was hardly a cheery chronicle of the “good old days.” Quite the contrary: most of the time it was a saga of unremitting toil, punctuated by poverty, misery, and grief. Specifically, life was normally short because it was a constant struggle with three of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: starvation, pestilence, and war.

The worst of these was war. Records of this and neighboring villages show that in 903 A.D. kinsmen of the Magyars ravaged the whole area and sacked the monastery of Schuttern two and a half miles from Oberschopfheim; that many starved during the bad harvests of 1338-1339; that mortality was ghastly during the Black Death of 1348-1351; that Oberschopfheim and other villages were destroyed during wars between local nobles in 1443; that more such wars, 1482-1486 and again in 1502, occasioned widespread pillage and suffering; that the destruction was repeated during the Peasants Revolt of 1525 and yet again by troops of William of Orange and local noblemen in 1569. From the thirteenth century to the eighteenth century scores of villages in southwestern Germany vanished under the relentless hammer of these recurring wars, most of which also brought pestilence in their train.

Perhaps the most interesting of these innumerable conflicts was the Peasants War of 1525. Though Marxist writers have managed to depict the revolt of that year as a forerunner to the Communist uprisings of the twentieth century, in fact it was precisely the opposite—a “reactionary” struggle against the growing power and pretensions of lay and clerical overlords. In the specific case of Lahr county, peasants from Lahr and Friesenheim made it clear in April and May 1525 that they had no quarrel with Holy Roman Emperor Charles V or with the city of Strasbourg but that they were determined to compel the abbot of Schuttern monastery to restore meadow rights taken from them in 1510. Accordingly, they demolished the walls around the monastery, plundered it thoroughly for four days, dug up the boundary stones in the fields, and forced the abbot to flee to Ettenheim and then to Freiburg. Alas for them! Their victory was short. In June 1525 they were defeated, forced to return their plunder, fined the huge sum of 6,000 gulden, and saw their leaders severely punished.1

The worst strife and the most material damage was done during the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). The whole area was ravaged by successive waves of Neapolitans, Burgundians, Swedes, Croats, Austrians, French, and a dozen others. They tortured the men, raped the women, commandeered the farm animals, ate and drank what they could find, stole everything that could be carried off—even to the bells in the churches—and burned what little remained. When one detachment of troops left Friesenheim, three miles away from Oberschopfheim, only the Lutheran church and a few houses were still standing.2

Despite the horror of these depredations, the ensuing drastic population decline was due less to hapless civilians being murdered by soldiers than to the plagues and starvation that almost invariably accompanied military operations in times past. Those peasants in and around Oberschopfheim who managed to survive both battles and pestilence struggled to subsist on potatoes, which had been introduced during the war and which marauding soldiers were usually too lazy to dig up. Potatoes were supplemented by rats, mice, snakes—even by leaves, grass, twigs, and roots. By 1630 the population had dwindled to about 600 in Oberschopfheim, by 1648 to perhaps 150.

Other collateral effects of the war were comparably grim. By 1648 little of either stored grain or seed grain was left. Almost all the farm animals were dead or gone, leaving peasants without plow beasts, meat, or fertilizer. Many fields lay uncultivated. The people, shorn of all their movable possessions, were scattered, and squabbles abounded among villages, families, and individuals as the dispossessed sought to recover what they had lost. If lands were regained, only small portions of them were farmed because the depopulation of towns had reduced the demand for food and had caused a fall in grain prices. Recovery was slowed further by governments that raised taxes for what was perceived to be the vital necessity of strengthening defenses.3 Popular superstition and fanaticism added the final dimension of suffering. In the nearby town of Offenburg some sixty persons were burned as witches from 1568 to 1630.

Such a succession of Dantesque experiences surely would have killed most twentieth-century urban people. Peasants, however, had learned from many centuries of grim experience that much of one’s fate was always in the hands of nature, the upper classes, or outside enemies and that little could be done about this. Consequently, everywhere in Europe they developed an incongruous mixture of resignation and indomitable pertinacity that often served them better than any purely rational response to their fate.4 One example here will suffice. In each of two villages in the neighborhood one old horse had managed to survive the murderous campaigns. The two hapless beasts were hitched together and the peasants began to plow once more.5

The respite was short. In Louis XIV’s war against the Dutch a bare generation later the Sun King’s Imperial opponents quartered their armies a mile away from the remnants of Oberschopfheim in 1675 and again in 1678. Sometimes they extorted “contributions” in money, horses, hay, wine, grain, or bread under the threat of burning the village if its inhabitants did not comply with their demands. Sometimes they did not trouble themselves thus but simply stole whatever they wanted from anyone who could be found—or caught. Not to be outdone in villainy, French troops tore up the walls and floors of Schuttern monastery in their search for presumed treasure. The Imperial troops of Montecuccoli riposted by sacking the village of Sasbach in 1675. Years afterward their successors degenerated into mere bands of robbers who pillaged the countryside indiscriminately.6 Little wonder that a new pastor, sent to Oberschopfheim in October 1676, began his baptismal book thus: “Dear reader: Do not be astounded that most names at the beginning of these records are not here; for the largest part of the parish wanted to get away from the money-hungry and looting soldiers and saw themselves forced to seek shelter far from their homes. At the same time the church books which my predecessor kept have been lost . . . In war there is nothing good, therefore we all implore peace.”7 But peace did not come to Oberschopfheim. Time after time during the next sixty years French troops destroyed local castles, sacked eighty of the ninety houses in Oberschopfheim, plundered much of the city of Lahr and its environs, and subjected the whole county to forced contributions.8

The aftereffects of war were sometimes nearly as bad as the conflicts themselves. In 1725 the abbot of Schuttern monastery brought suit in a civil court to compel the peasants of Friesenheim, Oberweier, Heiligenzell, and Oberschopfheim to pay him back taxes that had gone uncollected during the many wars provoked by Louis XIV. The villagers protested that they should not be required to pay because the French armies had either taken their crops or had prevented them from planting in the first place. Their appeal to equity was fruitless. The abbot won his case, though the peasants had to pay somewhat less in money, free labor, and farm produce than they did in normal times.9

Four years later residues from the same conflicts almost provoked an intramural “war” between Friesenheim and Schuttern. The people of Schuttern, pressed hard to pay off debts incurred during the French wars, decided to drain a meadow they had long shared with Friesenheim as pasture land. They planned to farm their half to get cash crops with which to pay their debts. Since there had long been much rivalry among the farm villages of Lahr county, it was no surprise that Friesenheim was unwilling to cooperate. So the peasants of Schuttern, backed by their abbot, simply went ahead alone. They dug a ditch to drain the meadow and fenced off their half. The Friesenheimers bided their time until the abbot was called away. Then, armed with agricultural tools, three hundred of them descended on the area, filled in the ditch, tore down the fence, drove their animals in to graze in the newly planted field, and defied Schuttern to do anything about it. Luckily, no blood was shed, and the whole dispute eventually evaporated in a long and inconclusive lawsuit.10

During the French revolutionary and Napoleonic era, the French were back in Lahr county once more. From 1796 to 1807 they intermittently extorted the usual money, food, and supplies and drove the villagers deeply into debt to buy straw from neighboring hamlets to supply the invaders’ animals. To add the proverbial insult to injury, these new pillagers were dogmatically antireligious and so confiscated lands belonging to the Oberschopfheim parish and to two monasteries. As usual, too, invading armies brought not merely violence and rapine but disease as well, in this case a typhus epidemic (1793-1794).11

Ordinarily, there is almost no way unarmed people can defend themselves against professional soldiers. In this instance, however, there lived in the neighboring village of Kuerzell, a scant three miles distant, a remarkable man named George Pfaff, a Gasthaus (tavern) keeper who managed to keep the French at bay for almost half a year (1796-1797). The feat was attributable about equally to amazing courage and to phenomenal luck.

As a reward for his exploits Pfaff was variously praised at Mass by the pastor of Kuerzell, was given an Austrian Lancer’s uniform by the abbot of Schuttern, and was awarded a gold medal by the Austrian general Merveldt.12 Pfaff’s deeds and his willingness to wear the Austrian uniform and medal presented to him indicated clearly enough that he recognized the emperor of Austria as his sovereign. Also, he obviously respected the abbot who bought him the uniform and the priest who praised him for his heroism. Yet soon after, when he was a tavernkeeper again, he served everyone impartially. Plainly, his paramount interests were local and personal, not national or ideological. It would be the same with Oberschopfheimers in both world wars, 125 to 150 years later. It was also the same with most of the inhabitants of Baden at the turn of the nineteenth century. Those men mustered into the army dutifully followed their prince wherever he led during the wars. Several thousand of them were captured by the French and pressed into service in Spain in 1808 and in Austria in 1809. By 1811, twelve thousand Baden men were being trained to support the catastrophic Napoleonic invasion of Russia that would follow in 1812. After Bonaparte’s defeat, a Czarist host rolled westward and replaced the French as an army of occupation along the Rhine. At once there began a new round of atrocities and new demands for contributions. During these occupations many Oberschopfheimers, who had somehow managed to survive the previous twenty-three years of the war, now fled to the mountains as their ancestors had done, leaving their unplanted fields to wolves and foxes.13

Those who stayed behind fared but little better. Everywhere food was scarce because all the potatoes had been taken by the armies of occupation. As an emergency measure soup kitchens were set up in Lahr city. Government agents went from house to house collecting bones for the indigent, and bread was sold below cost to the poor. In Lahr county about 22,000 gulden was spent for poor relief in 1816 and 1817. The whole dismal situation was summed up aptly on one side of a medallion struck in Nuremberg in 1817. It bore the inscription, “O give me bread! I am hungry.”14

Gradually, some nine hundred stolid, bruised, and exploited peasants straggled back to Oberschopfheim. They had suffered far more during the wars unleashed by Bonaparte than their remote descendants would endure in Hitler’s war (1939-1945). Tenacious as ever, they began once more to rebuild their community and their lives. This time they were assailed for decades by a coalition of all the elements. Immediately, the weather was so wet that crops rotted in the fields and starvation became rampant. This was followed intermittently over the next half century by floods from both untamed mountain streams and the Rhine river, which between them inundated large stretches of Lahr county. In 1831 there was a strong earthquake. Then between 1840 and 1847 more abnormally wet weather ruined most of the crops. To make matters worse, it flooded the low-lying wetlands and produced a population explosion among snakes. The whole dolorous litany was capped by a series of exceptionally cold winters that forced villagers to purchase expensive firewood. As in 1816-1817, soup kitchens were set up to provide at least a noonday meal for those inhabitants facing starvation.15 Inevitably, thievery flourished.

The catalyst in the crisis was failure of the potato crop. Potatoes produce more calories per acre than any grain crop, even rice. Thus in many parts of southwest Germany, where farms were tiny already and where peasants often married early and had large families, the population had grown rapidly even though there was as yet (1840) no major outlet in industry or crafts for the surplus people. This condition could endure only as long as potatoes remained plentiful and cheap. When crops failed, the result was less catastrophic than in the Irish potato famine a few years later, but it was...