- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

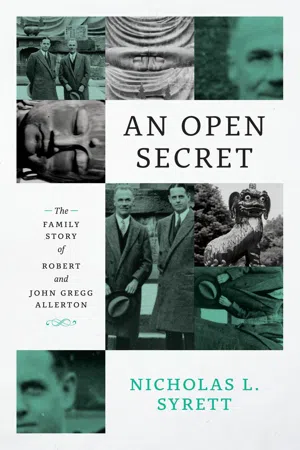

In 1922 Robert Allerton—described by the Chicago Tribune as the "richest bachelor in Chicago"—met a twenty-two-year-old University of Illinois architecture student named John Gregg, who was twenty-six years his junior. Virtually inseparable from then on, they began publicly referring to one another as father and son within a couple years of meeting. In 1960, after nearly four decades together, and with Robert Allerton nearing ninety, they embarked on a daringly nonconformist move: Allerton legally adopted the sixty-year-old Gregg as his son, the first such adoption of an adult in Illinois history.

An Open Secret tells the striking story of these two iconoclasts, locating them among their queer contemporaries and exploring why becoming father and son made a surprising kind of sense for a twentieth-century couple who had every monetary advantage but one glaring problem: they wanted to be together publicly in a society that did not tolerate their love. Deftly exploring the nature of their design, domestic, and philanthropic projects, Nicholas L. Syrett illuminates how viewing the Allertons as both a same-sex couple and an adopted family is crucial to understanding their relationship's profound queerness. By digging deep into the lives of two men who operated largely as ciphers in their own time, he opens up provocative new lanes to consider the diversity of kinship ties in modern US history.

An Open Secret tells the striking story of these two iconoclasts, locating them among their queer contemporaries and exploring why becoming father and son made a surprising kind of sense for a twentieth-century couple who had every monetary advantage but one glaring problem: they wanted to be together publicly in a society that did not tolerate their love. Deftly exploring the nature of their design, domestic, and philanthropic projects, Nicholas L. Syrett illuminates how viewing the Allertons as both a same-sex couple and an adopted family is crucial to understanding their relationship's profound queerness. By digging deep into the lives of two men who operated largely as ciphers in their own time, he opens up provocative new lanes to consider the diversity of kinship ties in modern US history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Open Secret by Nicholas L. Syrett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2021Print ISBN

9780226761558, 9780226638744eBook ISBN

9780226751665Chapter One

Allerton Roots

Illinois is today home to a number of landmarks that bear the name Allerton. The Allerton Hotel (now the Warwick Allerton) sits in Chicago’s Near North Side neighborhood alongside many other hotels on the city’s Magnificent Mile. The imposing entrance wing of the Art Institute of Chicago is the Allerton Building, and numerous collections and pieces within the Art Institute honor Allerton as their donor. Much farther south, the tiny town of Allerton, Illinois (population 291), sits amidst the cornfields in Vermilion County, southeast of Champaign and the University of Illinois, which itself hosts Allerton conferences at Allerton Park and awards annual Allerton scholarships.

Most, but not all, are named for Robert Allerton and his immediate relations. The Chicago hotel, which is part of a chain that also had a New York location, was originally begun in the 1920s by a distant cousin and named for their common ancestor, Mary Allerton, the last surviving passenger on the Mayflower. Those that are named directly for Robert or his father, Samuel, all attest to the influence of one family and ultimately demonstrate just how Robert Allerton came to be the subject of this book in the first place. Without the wealth of his forebears, there would, quite simply, be no Robert Allerton and John Gregg to write about. The choices that Allerton made to fulfill his same-sex desires were fully enabled and structured by his wealth. A Robert born to an Illinois farming family not only would be unknown to us today, but would have had his affinity for men constrained in any number of ways not experienced by the Robert who was born to the prosperous Samuel and Pamilla Allerton of Chicago’s Michigan Avenue. He likely would have married a woman and become a farmer himself or, if he was particularly enterprising, moved to Chicago, where he might have satisfied his same-sex desires in clandestine encounters with other similarly inclined men in the growing queer scene at the turn of the century. He would not have been in a position to take up with a long-term partner he referred to as his son, travel the world in search of queer pleasures, and make a long-lasting impact in the worlds of art and design. While the latter two claims verge on the obvious, it is worth emphasizing that the very possibility for fulfilling Allerton’s queer desires was predicated on his family’s money. Socioeconomic class structured the form in which Robert Allerton and subsequently John Gregg were able to live out a queer life.

When Robert Henry Allerton was born in 1873, his father, Samuel Waters Allerton, was already one of Chicago’s “Cattle Kings” and had begun to amass a good portion of the fortune that would sustain not only Samuel’s family but also Robert and John. But Samuel Allerton did not grow up with money. He had been born in obscurity in 1828 in upstate New York. The Allerton family story in America is one of triumph and of hardship, culminating in Samuel’s astounding success in an industrializing Chicago of the mid-nineteenth century. A brief trip backward situates Robert Allerton (and subsequently John Gregg) as part of a quintessentially American family story that begins as the Mayflower crosses the Atlantic ocean in the early seventeenth century and ends on a tiny Hawaiian island in the middle of the Pacific nearly four hundred years later.

That story commences with the sixteenth-century Puritan revolt against the Church of England. Isaac Allerton was born in England in the 1580s. Allerton was in his mid-twenties when he left England for Holland with his fellow Puritans as a result of the religious persecution they experienced because of their questioning and criticism of the Church of England. He settled in Leiden, where he married Mary Norris in November 1611; she gave birth to a son, Bartholomew, and two daughters, Remember and Mary. Fleeing persecution once again, this time in their adopted home in Holland, the Allertons and their servant, John Hooke, joined their fellow Pilgrims aboard the Mayflower in 1620 and set sail for what would become Plymouth Colony, which they hoped would be a permanent home for Puritans in the New World. Isaac appears in records as “Mr. Isaac Allerton,” indicating he was a man of wealth and status. Mary Allerton would give birth to a stillborn child while in Plymouth Harbor and would herself die during that first winter in Plymouth Colony. Isaac Allerton was remarried in 1626 to a woman twenty years his junior, Fear Brewster, daughter of preacher and Puritan leader William Brewster. They would have two children: Isaac Jr., born around 1627, from whom Samuel and Robert descend, and Sarah, born in 1633, who died in infancy.1

Isaac Allerton Sr. quickly rose to prominence in Plymouth Colony and then just as quickly fell into disrepute. He served as William Bradford’s assistant governor during the colony’s early years and in 1627 became one of the undertakers of the colony’s debt; in that capacity he made several trips back and forth to England to negotiate with the colony’s creditors. At the same time, he used the colony’s credit as collateral in starting a number of business ventures of his own, ventures that failed, leaving the colony further saddled with his debt. In addition to being friendly with Roger Williams—forced from Plymouth for his heresy—Allerton brought the social reformer Thomas Morton with him on a trip back to Plymouth in 1629 and allowed him to stay at his home. Morton had been condemned by the Puritans at Plymouth for his liberal Christianity and for what they believed to be his far too intimate relations with Native Americans at his Virginia colony, Merrymount. Allerton’s seeming approbation of Morton did not bode well for his own continued acceptance among the colonists at Plymouth, and Allerton was forced to leave. He settled first at Marblehead, Massachusetts, and later, after being forced to leave Massachusetts, in the colonies at New Amsterdam and finally in New Haven, where he died, insolvent, in 1659. His daughter, Mary, was the last survivor of the Mayflower, dying in 1699 at the age of eighty-three. The first generation of the Allertons in America had begun with promise but had ended in obscurity. That said, the very fact of the Allerton family’s arriving so early in the American colonial project insured that at least some of their descendants would have access to opportunities for amassing wealth that were rarely available to those who arrived in America as indentured servants or slaves or who immigrated later after much of the land once occupied by Native Americans had been claimed by other white settlers.2

For an additional four generations, the Allertons lived in Connecticut, New York, and Rhode Island, with occasional forays into Virginia. Their fortunes rose and fell, and while an occasional Allerton distinguished him- or herself (Robert’s great-grandfather Reuben Allerton served as a doctor in the Revolutionary War), for the most part the Allertons, like most Americans, toiled away out of the public eye. Robert Allerton’s grandfather, Samuel Waters Allerton Sr., was born December 5, 1785, in Amenia, New York. On March 26, 1808, he married Hannah Hurd. Like his father, Reuben, he trained to be a physician but decided to pursue a trade instead and became a tailor, opening a country store. He also invested in a woolens factory in the late 1820s, but when protective tariffs were reduced in the 1830s, he and many others like him were reduced to ruins. Samuel Waters Allerton Jr. came into the world on May 26, 1828, the ninth child of Samuel and Hannah. When a child of seven, he witnessed the ruin of his father: the sheriff had come to sell the Allerton property, which was claimed to settle Samuel Sr.’s debts. As two highly prized horses were being bid upon, Samuel Jr. saw his mother in tears. According to Walter Scott Allerton, chronicler of the Allerton genealogy, Samuel threw his arms about his mother’s neck, promising that he would be a man and care for her. This experience would prove foundational for the younger Samuel. In speaking about his father and mother later in life, Samuel recalled: “He was one of the most honest, straight men in the world. Much too honest to make a good trade for himself; very hard working and industrious man. My mother was one of the best mothers in the world; as true as steel, very genial and pleasant—would have enjoyed life very much if she had not been so poor. Had she been the man, and Father the woman, they would have made better headway in the world.” In these recollections of his parents, recorded after he had made his fortune, Samuel was clear about what it took to be successful, attributes he believed his mother possessed more than his father.3

The lesson learned from his father’s ruin was fundamental for Samuel: “When I arrived at the age of 11 years I saw if I ever had any money or position in life I would have to get it myself, and as we had been poor, and always went with the best people in the country, we felt it more, and I made up my mind to gain money, and I commenced at 11 to save and work; had no taste for school—[my] mind all seemed to be on how to get money.” The financial disaster forced his father to rent a farm to make ends meet; the younger Samuel began to work on that farm at the age of twelve. Eventually they had saved enough to buy a farm of their own in Wayne County, New York. Samuel and his elder brother Henry then set aside enough money to buy their own farm, Samuel’s first endeavor in agricultural ownership. He also began, intermittently, to trade in livestock. In time he realized that he knew as much about the trade as the dealers with whom he interacted and decided to sell his portion of the farm he owned with his brother and invest the money in making his entrance into the livestock trade. His brother counseled him: “If you continue as you are [in farming], in a few years you will own the best farm in this country; but if you wish to try the live stock trade, all right, we will settle on this basis. This is all the advice I have to give you; you will run across smart and tricky men, but they always die poor—make a name and character for yourself, and you are sure to win.”4

Throughout his late teens and early twenties, Samuel drifted between the sale of livestock and farming with his brothers. By the 1850s he had moved west, continuing to trade in livestock. While in Illinois, he met Pamilla Thompson, daughter of a farmer and landowner in Fulton County, about two hundred miles southwest of Chicago. As he was making plans to pursue Pamilla, the economic Panic of 1857 gripped the country. As Samuel put it, “We had 400 head of cattle on our hands and cattle dropped $1.00 per hundred and we lost all we made the first year, and I was taken with a very bad fever and was laid up for 6 months.” In the wake of his financial failure and his illness, he returned home to upstate New York, where he partnered again with his brother in a dry goods store. Tiring of that after a year, he “got well and courage came back,” and he again headed west, this time with his share of the store and some borrowed money, in search of Pamilla Thompson.5

Before marrying Pamilla, he began to trade hogs in Chicago; he wanted to have enough money to feel that he could support a wife, for as he said later, “I did not like to marry until I felt I could take good care of her.” Samuel Waters Allerton Jr. married Pamilla Wigdon Thompson in July 1860, when he was thirty-two and she was twenty. While he did not have much money, he had “what was better than money—the courage and knowledge of how to trade,” which helped him to “get over the diffidence with the girl I loved better than life.”6

From that point on, Samuel’s story is one of a steady rise upward. In the midst of the Civil War, in 1863, as the federal government was encouraging the formation of national banks, Samuel and five associates founded the First National Bank of Chicago. This was both an astute financial move—Samuel and his children would remain principal shareholders for some time—but was also because Samuel had difficulty in securing funds to purchase large numbers of hogs. He was well known for having cornered the Chicago hog market in May 1860—purchasing all the available hogs in Chicago following a sharp decline in prices—but was only able to secure loans to do so after local bankers received three telegrams from New York banks vouching for his good name. The establishment of the First National Bank of Chicago and others like it would thus make large sums of capital available to Chicago businessmen like Allerton intent on developing their fortunes.7

Samuel’s next great project was the founding of the Union Stock Yards, which he, along with other businessmen, helped to establish in 1865. For many years, livestock in Chicago had either been kept in small yards near taverns and saloons or increasingly, after 1848, in smaller commercial stockyards developed expressly for that purpose. A number of factors increased the need for a large stockyard that was more conveniently located near the railroad. The first of these was the expansion of the railroad westward, which made Chicago a hub for converging trains and their cargo as well as turning Chicago into a commercial center in its own right. A second factor was the closing of the Mississippi River for north–south commerce during the Civil War, which only increased the traffic through Chicago, particularly of grains and livestock coming from the Midwest and heading east. Both of these factors also brought larger numbers of meatpackers and their livestock to Chicago. This was all good news for a man like Samuel Allerton, whose livelihood was in livestock. But in order to accommodate the influx of hogs, sheep, and cattle, Chicagoans had to build a large facility located near the railroads. Joining with other packers and railroad companies, Allerton founded the Union Stock Yard and Transit Company. The railroads had purchased 320 acres south of the city, and the corporation proposed to spend nearly one million dollars to “fence and plank [the yards], construct suitable hotels and other buildings, and connect the yards with all the railroads entering the city, by constructing railroad tracks, which shall be free to the stock business of such roads.” The guiding principle was to establish a giant central location in which buyers, sellers, livestock, and railroads would all converge for the convenience and financial betterment of all concerned (save the livestock, of course). Construction began in June 1865.8

Throughout this period, Samuel and Pamilla Allerton had been growing steadily richer, as had their fellow Chicago Gilded Age industrialists. In 1863, three years after they were married, Pamilla gave birth to a daughter, Kate Reinette Allerton. A decade after that, she gave birth to Robert in their home on Michigan Avenue. By this point the Allertons were part of an established social set that included Marshall Field, of the eponymous department store; Potter Palmer, who worked with Field on the department store and also founded the Palmer House hotel; and Adolphus Clay Bartlett and William Gold Hibbard, founders of Hibbard, Spencer, Bartlett & Company, at the time one of the country’s foremost hardware companies (now True Value). These men and their wives made up some of the elite social set in Gilded Age Chicago, the equivalent of New York’s Vanderbilts, Astors, Rockefellers, and Carnegies. While the truly old money would likely have looked down their noses at these nouveaux riches arrivistes and the New Yorkers no doubt did not consider the midwesterners to be their equals, families like the Fields, the Palmers, and the Bartletts were at the apex of Chicago society. Samuel Allerton’s ties to agriculture and the hog market, as well as his less-than-polished table manners, set him slightly apart from some of their neighbors, but not so much that Robert and Kate were unable to enjoy all the privileges of growing up with others in their elite social set.9

Robert spent his childhood playing with the children of these elites: Ethel and Marshall Field Jr., Honoré and Potter Palmer Jr., Frederic Clay Bartlett, and Franklin Hibbard. As one of Robert’s employees would later recall, “In the backyard of his family house on South Michigan Avenue in Chicago he had a replica of his parents’ house as a play house. There on a little stove he cooked pancakes for his little friends made from batter an indulgent cook whipped up for him.” It was, by all accounts, an exceptionally privileged childhood for both Kate and Robert. As Samuel’s fortune rose, he moved the family to Prairie Avenue, alongside the rest of the city’s elite on Millionaires’ Row. The Fields lived on the same block in number 1905; the Pullmans, of the Pullman Palace Car Company, were at 1729; meatpacking magnate Philip Armour and his family were at 2115. When the census taker came to the door of the Allerton home at 1936 Prairie Avenue in 1880, the household also included Pamilla’s younger sister Agnes, as well as a coachman, a gardener, a butler, a cook, a seamstress, and a laundress. In 1884 Samuel purchased a summer home among other wealthy families on the shores of Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. They called the lodge “The Folly,” supposedly because when Samuel had returned from his trip to Wisconsin after purchasing the twenty-six-acre property, his second wife, Agnes, had exclaimed, “A fishing lodge? Heavens[,] Samuel, that is sheer folly!” The Allertons soon transformed the more rustic lodge into a magnificent redwood structure, moving the original lodge on the property and then constructing the new dwelling around the original core. Samuel had managed to give Robert and Kate a childhood not only free of the economic insecurity of his own youth, but a life of privilege and luxury.10

Four events occurred in the early 1880s that would have a profound effect upon Robert’s childhood and indeed the rest of his life. In 1880 Robert and Kate, who were then six and seventeen, contracted scarlet fever. Most common among young people between exactly those ages, scarlet fever is epidemiologically related to strep throat and is similarly spread by coughing and sneezing. While now easily treatable, in the late nineteenth century, scarlet fever had no known cure; its symptoms were sore throat, fever, headaches, rash, and swollen lymph nodes, and it could lead to arthritis, rheumatic fever, and inflammation of the kidney. In many cases, the disease felled entire families. In the case of both Robert and Kate, it led to deafness, likely caused by sinus infections or abscesses of the ear. Sparing no expense, their parents sent them to Vienna, Austria, to be treated by the renowned Dr. Adam Politzer, specialist in otology, where both were operated upon in hopes of restoring their hearing. In Kate’s case, the surgery was partially successful. Robert did not fare as well, and he was left with permanent hearing loss. He was not completely deaf, and over the course of his life, he partially made up for his hearing loss with an ear trumpet and later with a hea...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Allerton Roots

- 2 Robert Allerton’s Queer Aesthetic

- 3 Travel and Itinerant Homosexuality

- 4 Becoming Father and Son

- 5 Lord of a Hawaiian Island

- 6 Queer Domesticity in Illinois and Hawai‘i

- 7 Legally Father and Son

- Conclusion: John Wyatt Gregg Allerton

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index