![]()

1 You Are What You Risk

WHAT MAKES A sixty-three-year-old woman decide to try to become the first person to ride over Niagara Falls? That’s what Annie Edson Taylor did in 1901, traversing the iconic waterfall in a souped-up pickle barrel as part of a dubious get-rich-quick scheme. A schoolteacher from Auburn, New York, Taylor had enjoyed teaching stints from California to Tennessee, Indiana, Texas, and Alabama; from Mexico City to Washington, DC, to Chicago. Still, she’d had to supplement her living expenses for most of her life from inheritances: her father passed away suddenly when she was twelve, then her husband died in Civil War combat, leaving her widowed.

After late-in-life dance training, she opened a dance school in Bay City, Michigan. When that failed, she tried teaching music in Sault Ste. Marie on the US side of the Canadian border. When the idea of going over the Falls struck her, Taylor’s inheritance was dwindling, and she had been having trouble getting steady work. Tired of leaning on her sister-in-law for support, Taylor was searching for a way to make money honestly and fast.

The Pan-American Exposition was planned for Buffalo, not far from where she had moved for another job teaching dance, when she came up with a plan. “Reading the New York paper about people going to the Pan-American exposition, and from there to Niagara Falls, the idea came to me like a flash of light,” she later wrote. “Go over Niagara Falls in a barrel. No one has ever accomplished this feat.”

By the time Taylor decided to carry out the stunt, which took place on her sixty-fourth birthday, her funds were running so low she felt she had nothing to lose. She believed that she would benefit greatly if she succeeded, which led her to discount the risk. She reduced risks by making every preparation you could imagine.

A Times-Press reporter asked her what put such a suicidal idea into her head. She replied: “It is not a suicidal idea with me. I entertain the utmost confidence that I shall succeed in going over the Falls without any harm resulting to me. The barrel is good and strong and the inside will be cushioned so that the rolling movement will do me no harm. Besides, I shall have straps to hold fast to. There will be a weight in one end of the barrel so that air can be admitted through a valve in the upper end where my head will be located.”

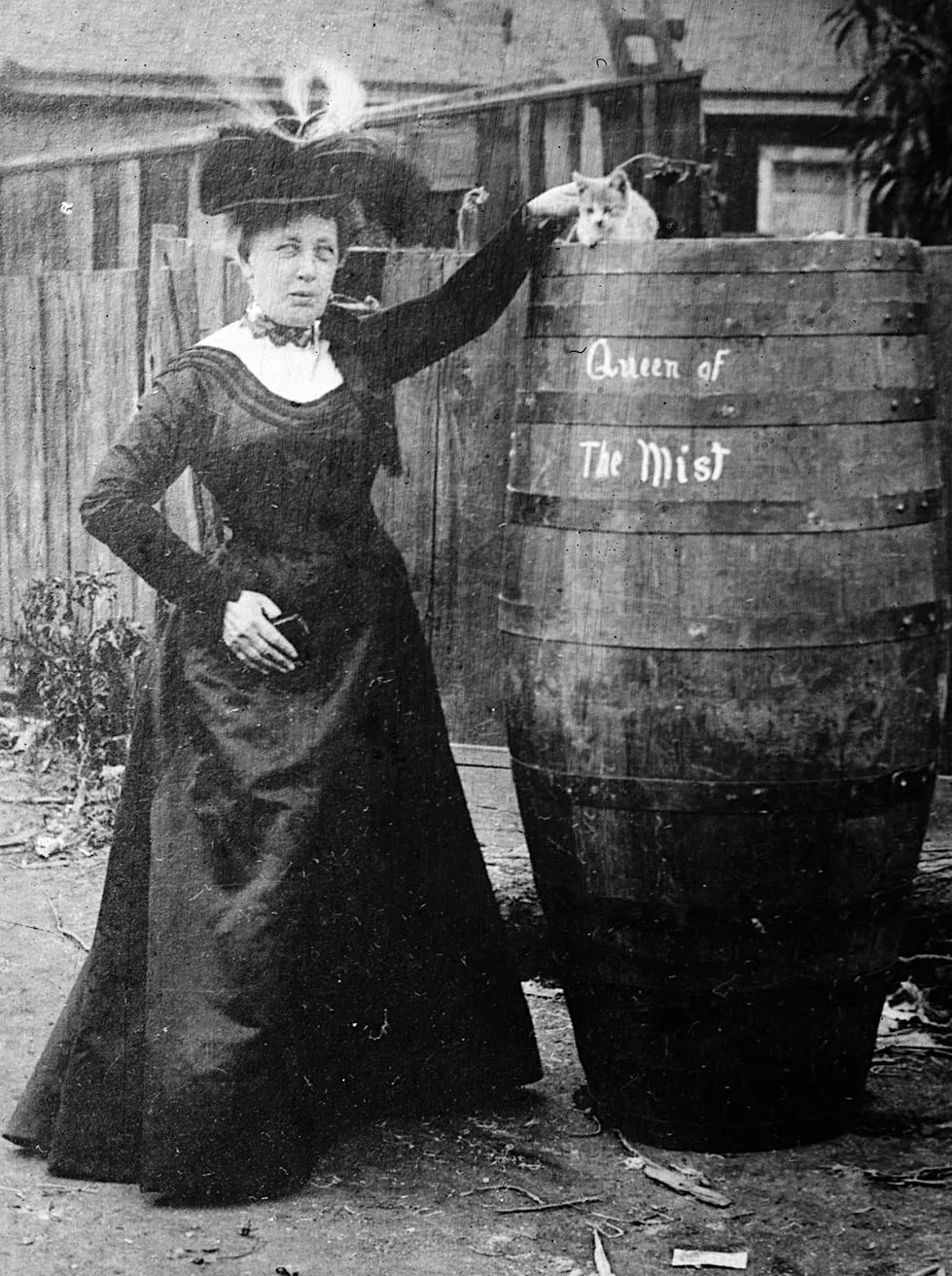

Taylor customized a 4.5-foot-tall, 3-foot-wide pickle barrel made of Kentucky white oak, installing a leather harness and cushions for protection and air holes with cork stoppers and a rubber tube, and attaching a 200-pound anvil to the 160-pound barrel to be sure it went down bottom-first. She tested it by sending her cat over Horseshoe Falls in the barrel. The cat survived.

Annie Edson Taylor, the first person to go over Niagara Falls in a barrel and survive, standing next to the barrel and her cat who went over the Falls in a test run of the barrel. Photo credit: Bain News Service, 1901. George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress).

She monitored the weather carefully, cutting short her first attempt because of strong winds the day before she finally succeeded. On her sixty-fourth birthday, October 24, 1901, shortly before 4:00 p.m., Taylor climbed into the barrel. Her crew towed it to the middle of the river at Grass Island, about a mile north of Horseshoe Falls. Her cat may or may not have been with her. Her crew pumped air into the barrel with a bicycle pump and released it at 4:05 p.m.

The carnival promoter Frank M. “Tussy” Russell, whom Taylor had hired to drum up publicity, watched particularly nervously since both Canadian and American officials reportedly had threatened to charge him with manslaughter if the trip failed. (She had responded by threatening to drown herself if they tried to prevent her from attempting the feat.)

Taylor, in her pickle barrel, made her way down the river through churning whitewater rapids until she finally pitched over the edge of the falls at 4:23 p.m. and reemerged a minute or so later from the mist at the foot of the precipice. Sixteen minutes later, the crew pulled it out from between two eddies and dragged it ashore, with several thousand people watching along the rapids and below the Falls.

Taylor was mostly unscathed during the 158-foot fall, save for a three-inch gash behind her right ear, likely suffered as her team sawed the top off of the barrel before helping her out. She claimed to have lost consciousness during the drop and complained of whiplash. “I would rather face a cannon knowing that I would be blown to pieces, than go over the falls again,” she told a reporter.

Despite all her planning, in the end, Taylor got sideswiped by a risk she hadn’t foreseen: betrayal by her manager. She didn’t even get to keep the barrel, which Tussy reportedly stole before traveling around the country with a younger woman whom he claimed was the one who had gone over the Falls in it. Tussy and Taylor had knocked twenty years off of her real age when she talked to reporters, so the imposter probably looked more like what people imagined based on who she had claimed she was.

Apart from a few speaking engagements, the stunt didn’t end with the fame and fortune she’d hoped in styling herself as “Queen of the Mist.” Despite her life of excitement, her stage presence was said to be, to put it kindly, lacking. To support herself, Taylor resorted to hawking mementos of her achievement—miniature barrels, photos of herself, and booklets describing her feat—on the streets of Niagara and posing for pictures in exchange for tips. She lived another twenty years and died in poverty in Lockport, New York.

Annie Edson Taylor’s life and legacy were all about risk. Her story, which bears many of the hallmarks of a classic risk-taker’s, offers some clues as to what experiences and attitudes shaped the choices she made about the chances she took. Two sudden deaths of loved ones had demonstrated how fleeting life was. A financial safety net for much of her own life had given her the freedom to take chances, which she chose freely, claiming to have crossed the continent coast to coast eight full times. Despite her earlier comfort, by the time of the stunt, she hardly had two pennies to rub together. The perception that the stunt was a ticket to financial success would have reduced how risky she thought it was because the more benefit we see to something the less risky we perceive it to be. Her detailed preparations gave her a sense of control, and thus a higher risk tolerance.

But her choice was as much a product of the times and the society as it was of her personal influences and experiences. Amid great economic and social tumult and ambition, her decision was part of the zeitgeist. The Gilded Age had been drawing to a close as a time of plenty gave way to scarcity, making it hard for Taylor to bring in an income. The stock market had crashed a few months earlier in the May Panic of 1901. In a time of instability—perhaps not so different from today—people who felt they had nothing to lose may have felt they had license to take bigger risks. The suffrage movement was beginning to regain momentum. President McKinley was assassinated weeks before her stunt, and the adventurous Theodore Roosevelt, the youngest president ever at forty-two, had just been sworn in.

Over the century after Taylor’s death, five people died trying to make the same leap over the Falls; another eleven survived it. Was their risk worth it? They are the only ones who can answer. But those of us who are still on the planet can benefit from asking similar questions of ourselves when we think about the risks we have taken and the ones yet to come, because they say everything about who we are and the world in which we live.

YOUR RISK FINGERPRINT

Just as Taylor’s risk decisions defined her life and legacy, each of the risks every one of us takes tells the world who we are. Risk explains everything from the mundane choices you make throughout the day—at home, work, and as a citizen—to the widely impactful actions of CEOs, mayors, presidents, and world leaders.

What you decide to have (or skip) for breakfast. Whether to go to the gym or sit on the couch and eat pizza. How much time to leave to get to the airport to catch a flight. Whether you speed or jaywalk or remember to look both ways when crossing; whether you wear a seatbelt in the car or pay attention to the bus driver or train conductor’s pleas for standing passengers to hold on.

Whether you’re going to procrastinate or meet that deadline. Whether to speak up in that important meeting where your boss is proposing a questionable course of action. Whether to keep your head down at your current job or stretch for a better position. Whether to push your clients for more business or to dump the ones that aren’t worth your time so that you can focus on landing bigger accounts. Whether to launch that new product even though you’re not sure you’ve worked out the bugs, or wait and take the chance that your competitor will get to market first.

Whether to tell your best friend that their significant other is bad news, taking the chance that you will upset them no matter if you are right or wrong, or to stay silent, and risk watching them make a big mistake. Whether to put your life savings into that penny stock your cousin has a hot tip about.

What makes people take risks? Why do some of us make the preparations we need to succeed, but others miscalculate, often with fatal results? Why do some of us think of danger where others see opportunity? The answer matters for decisions people and nations make every day, from the mundane to the existential, involving relationships, health, finance, safety, career, and community. The forces behind our risk decisions are especially relevant for businesses and investors, whose choices create and destroy wealth and livelihoods, careers, and reputations.

The reasons we choose to face or ignore the dangers and opportunities in front of us may surprise as much as they enlighten. So many things shape how we perceive and rank risks: demographics, upbringing, career choices, religion, geography, culture, past experiences, generations, media, decision processes, organizational design… the list goes on. But unexpected factors—your height, what you look like, what you ate today, what language you speak, and what music you listen to—play a bigger role than you might think. Even the people who consider themselves to be highly rational, are buffeted by emotions, cognitive biases, and the rush of hormones through our veins. We ignore them at our peril.

These often unconscious influences shape how sensitive we are to risks: that is, how likely we are to judge something as risky or not, how worried it makes us, and even whether we notice it at all. They mold our risk tolerance and attitudes: how much risk we think is worth bearing, and whether we distinguish between “good” risks—that is, opportunities like taking a new job or trying something for the first time—and “bad” or “dangerous” risks—like, say, making questionable bets with other people’s money or committing crimes. Finally, they affect whether or not we stay in our comfort zones and how we behave in the face of a risk. Heading off a risk can be risky in and of itself. So can staying in an extreme comfort zone by doing everything you can to avoid risks.

RISK FINGERPRINT: The combination of personality traits, experiences, and social context that is a core component of each person’s identity.

Each one of us has a risk personality that is as distinct as a fingerprint. Our risk fingerprints start with our underlying personality traits, which you might think of as the ridges, arches, loops, and whorls that give the fingerprint structure and make it distinctive. Our experiences alter the fingerprint much as a cut might leave a scar.

Just as a real fingerprint offers forensic analysts clues to identity, the risk fingerprint offers a window into who each of us is: how we feel about authority and power, about our sense of human agency, how we relate to each other in groups, and broader cultural differences that can make societies particularly risk sensitive or risk blind. It sheds light on what people hope and fear—and why—and how much power they feel they and their leaders have over the world around them.

RISK ECOSYSTEM: The cultural, social, policy, and economic environment that affects the risk decisions of individuals and organizations.

The ecosystem in which we live and work—the cultural, social, policy, and economic environment that heightens risk or provides a safety net—smooths out or accentuates our personality. Finally, our risk habits alter the print further, just as how well we care for our hands determines the softness or roughness of our skin.

Our lives depend on what we believe about risk and the choices we make because of what we believe. “Risk has everything to do with survival,” the British psychologist Geoff Trickey, who specializes in risk and personality and with whom we’ll spend more time shortly, told me. “The balance between risk and opportunity is the line between life and death.”

How we perceive and weigh the threats and opportunities in front of us, which ones we embrace and which ones we reject, shapes our futures as individuals, workers, communities, and nations. Risk personality traits are important to each one of us and our intimate relationships. Their dynamic becomes exponentially more complex and exaggerated when we come together in groups.

No matter where you work or what you do, you cannot separate your success or failure from your ability to respond to anticipated changes, what risks you are willing to take, how well you have created a safety net in case of unanticipated events, and how those attitudes complement or clash with the people around you. Risk defines nearly every aspect of our personalities, our work, our leisure time, and how our societies function. The better you understand and evolve your relationship with risk, the more likely you are to succeed in any of these realms.

THE BIGGEST RISK IS STANDING STILL

An adventurous young family I know is a great example of how awareness of your own risk fingerprint can help you to make important changes that help you to face uncertainty and thrive. While they were still in their twenties, Megan and Marty Bhatia built several real estate development businesses bringing sustainable practices to rough neighborhoods, including supplies, construction, and brokerage. They had fourteen employees and owned a nice home in Chicago’s trendy West Loop neighborhood.

But then the 2008 financial crisis and real estate crash hit. They had borrowed heavily and found themselves owing nearly twice what their assets were worth. Marty’s mentor in the industry blew his head off with a shotgun. On the street one night, they stopped to help a man who looked distressed and was wearing multiple hospital bracelets. He was suicidal after losing $100,000 and his restaurant when the market crashed, but he did not owe anything close to the Bhatia’s more than $1 million in debt. The interaction was powerful: “It was then that I realized that we were in much better position mentally and emotionally because Marty and I had each other and we had our family,” Megan said. “He was obviously someone who had recently been very professional, lost it all, and didn’t have a support system.”

They pushed through with the help of their families, renegotiating debts down, keeping things together with Megan selling real estate for another firm and Marty starting a technology services company, and focusing on what they were grateful for. They avoided foreclosure and bankruptcy. As the economy recovered, so did their business. It felt as if they’d lived seven lives, even before they were thirty. Still, as time went by, they began to feel trapped. Their home cost more than they wanted to pay, and they worried about a new recession. Once their twins were born in 2015, they began to worry that traditional approaches to raising kids wouldn’t cut it in the future economy. That feeling kept growing.

Finally, late in 2018, they decided to sell their home and everything in it and set out to spend a year traveling the world with the twins. They could think of no better way to teach the twins to have confidence in themselves in new situations. “In the past, the idea of losing our home would have caused massive stress,” Megan said over coffee at a Lincoln Park café as they were getting ready to set off around the world. “Now, the idea of owning a home stresses us out,” Marty countered.

Over the next year and a half, they lived in Brazil, Chile, England, Belgium, Spa...