eBook - ePub

The Digital Pill

What Everyone Should Know about the Future of Our Healthcare System

- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Digital Pill

What Everyone Should Know about the Future of Our Healthcare System

About this book

Information technology is changing healthcare in numerous wide-ranging aspects, including significantly improving the overall quality of patient care and therefore helping to reduce limitations in people's daily lives.

The Digital Pill reflects on how digital technologies can combat chronic diseases including diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular, respiratory and neurodegenerative diseases as well as mental disorders. Chronic diseases touch every family, generate infinite suffering and cause the lion's share of every countries' healthcare spending across the world.

The authors carefully study a broad selection of contemporary companies and healthcare organizations that are shaping digital healthcare. They report pioneering cases from large and small technology, insurance, and pharmaceutical companies as well as healthcare providers of all sorts across the globe and bring forward patterns and corner stones of an affordable and patient centric digital healthcare. The Digital Pill is essential reading for anyone working in, engaged with or interested in understanding the future of healthcare.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Digital Pill by Elgar Fleisch,Christoph Franz,Andreas Herrmann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & IT Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Will the Healthcare System Become a Victim of its Own Success?

Chapters

1. Medical Progress is a Success Story that Comes with Consequences.

2. Non-communicable Diseases are Straining Our Healthcare System.

3. Digitalization Will Be a Key Success Factor for the Healthcare System of the Future.

Chapter 1

Medical Progress is a Success Story that Comes with Consequences

The main theses of this chapter:

• The medical progress of the past 100 years is the investment of the century. In the space of only 100 years, our life expectancy has doubled.

• Antibiotics and vaccines played a decisive role in the battle against infectious diseases.

• As life expectancy has increased, however, this hasn’t always meant improved quality of life in old age. The years we gain are often accompanied by chronic illnesses. Today we are better equipped to survive diseases such as heart attacks or cancer but as a result, we more and more frequently have to live with these illnesses.

• Without the mutual support provided by those with health insurance or the support of taxpayers (in the case of state-funded systems), medical progress does not reach everyone.

• More than half of all Americans who file for personal bankruptcy do so as a result of medical debt.

Let’s start with some good news: In only 100 years, our life expectancy has doubled. And not just in wealthy, developed nations. As the twentieth century began, a human being could expect to live about 40–46 years. In the meantime, average global life expectancy has risen to 72 years. In India today, people actually live three times as long as their ancestors did 100 years ago; life expectancy in that nation has increased from 24 years at the beginning of the twentieth century to all of 69 years [1, 2]. These numbers stand for billions of human lives – people who now enjoy more wealth, education, and longevity than any other generation that ever lived on our planet. If we consider that human beings have been around for more than 150,000 years, this amount of progress in only one century is nothing less than spectacular.

What made this amazing success story possible? Of course it doesn’t just come down to medical advancements. Growing prosperity, improved nutrition, and better hygiene – clean drinking water, regular waste, and wastewater disposal – as well as the peace that spread across Europe and other parts of the globe following the two world wars have all played a part. However, the primary reason for the increase in life expectancy is the progress made in combating infectious diseases. Until a few centuries ago, such illnesses were the most common cause of human mortality. Becoming infected was often a death sentence, one that robbed many of life during infancy. At the beginning of the twentieth century, one in 10 children in the United States still died before their first birthday. Back then the most common causes of death in young children were pneumonia, influenza, tuberculosis, and gastroenteritis [3].

But then the tide turned. More than any others, two medical innovations have proven to be particularly effective weapons in the fight against infectious diseases and therefore responsible for the increase in human life expectancy: antibiotics and vaccines. The story of the discovery of penicillin, the first antibiotic, has become a modern legend that most of us learn at school. Bacteriologist Alexander Fleming returned to his laboratory in London after a long summer vacation with his family. He had a reputation as an excellent researcher but an untidy one. Before leaving town, Fleming had started some bacteria cultures in Petri dishes. When he went to examine them upon his return, he saw that one of the cultures was contaminated and mold was growing in the Petri dish. When he looked more closely, Fleming noticed that the bacteria culture was not growing in the area surrounding the mold. So he started studying it, and discovered it belonged to the genus of Penicillium. This was why he named the new substance he went on to develop “penicillin.” It was to become the most effective substance available for fighting bacterial infections at the time.

Fleming’s discovery marked the start of the age of antibiotics. “When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn’t plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I suppose that was exactly what I did,” as Fleming would later say [4, p. 366]. Antibiotics like penicillin have saved hundreds of millions of human lives. Exact estimates are difficult to make – but the antibiotics produced by the pharmaceutical companies Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Roche alone have been prescribed billions of times since their approval. In addition, it is hard to imagine that medical advances like organ transplants would ever have been possible without antibiotics.

Alongside antibiotics, the development of vaccines played a major role in raising human life expectancy. The amazing success of vaccines becomes particularly clear when we look at the first viral disease – a disease caused by a virus − for which one was developed: smallpox. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart suffered from it, as did Abraham Lincoln and Josef Stalin. These three men survived, although some bore considerable scars for life. Smallpox is one of the most dangerous and deadly diseases ever to affect the human race – every third person who contracts it will die as a result. Even in the twentieth century, more than 300 million people died of smallpox before it was finally declared eradicated in 1980 [5].

And what made this possible? The development and distribution of the smallpox vaccine.

When a healthy person is vaccinated, they are given a weakened form of the virus to stimulate the production of antibodies in the immune system. If the vaccinated person later comes into contact with the actual pathogen, their immune system is prepared and can fight and destroy the virus.

Edward Jenner, a country doctor from England, is considered one of the fathers of the widespread immunization that we know today. Many of his patients were milkmaids, who often became ill from cowpox, a milder form of the poxvirus. And Jenner noticed that none of the milkmaids caught the dangerous and often deadly form of the human virus. Based on this observation, he developed a method in which he inoculated healthy individuals, including his own son, with the secretion from cowpox blisters. The subjects then experienced a mild form of the infection. Later Jenner infected the same individuals with the dangerous smallpox virus – and miraculously, they remained unaffected. This marked the birth of mass immunization, which even today is still called “vaccination” – revealing the origin of the practice. Because “vacca” is nothing other than the Latin word for “cow” [6].

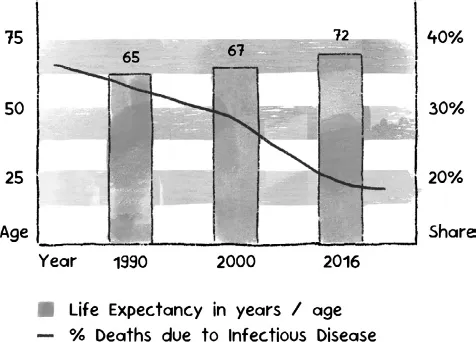

These victories don’t mean we can rest on our laurels. Keeping infectious diseases in check is an ongoing battle, as the recent painful experience of the coronavirus pandemic shows. We need to keep developing new generations of virostatic agents and vaccines; novel viruses and bacteria have to be countered with good pandemic preparedness. Skepticism about vaccines among some segments of the population and the resulting insufficient vaccination rates, has caused a resurgence of almost forgotten diseases like measles. So intervention and education are important here as well. But one thing is certain: vaccines and antibiotics have turned the tide in our fight against communicable diseases, resulting in a fundamental change in our understanding of human health. In 1990, one in three people still died of infectious diseases; today it’s only one in five. These advances also meant an increase in life expectancy, most recently from 65 years in 1950 to 72 years today (Fig. 1.1). This development bears witness to the success of medical progress but is also the source of new challenges.

Fig. 1.1. We Live Longer and Die Less Frequently of Infectious Diseases: Life Expectancy and Percentage of Deaths Caused by Infectious Diseases. Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington (2019). Share of death from infectious disease of total deaths, Worldwide, All Genders; Life Expectancy in Years.

More Years – To Suffer Ill Health?

For the most part, more years of life also mean better quality of life. In the past, it was normal for every family to have at least one child who died young. It was rare to live to see your great-grandchildren. Between 1950 and 2000 life expectancy in Germany, for example, rose from 64.6 years for men and 68.5 years for women to 78.4 and 83.4 years, respectively [7]. But these longer lives also presented society and individuals with new problems.

Medical advancements have not only led to a decrease in infectious diseases, but also enabled us to successfully treat many non-infectious diseases that would almost certainly have proved fatal a hundred years ago, like cardiovascular disease and cancer. However, there is a fundamental difference here to our fight against viruses and bacteria – because unlike infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) often cannot be cured, but only halted or slowed. A study by the University of Southern California shows that we are not “heathier” per se and therefore live longer. Instead, thanks to medical progress, today we are better equipped to survive diseases such as heart attacks or cancer – but as a result, we more and more frequently have to live with these illnesses [8].

Before the medical innovations of the twentieth century, a disease usually ended in either recovery or death. Today many of the years of life we have gained are frequently also years, in which an individual will endure one or multiple diseases. This can mean substantial suffering for the patient and their family, and poses new challenges for healthcare systems.

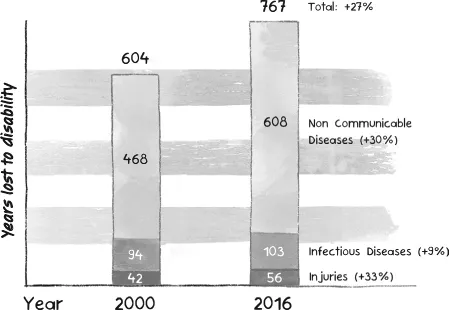

Health economists came up with an indicator for this in the late 1990s, which they called “years lost to disability,” or YLD. This means years that the person missed out on because they were severely impaired by their illness. Sometimes the indicator is expressed as “years lived with disability,” which paints a somewhat gentler picture. The World Health Organization (WHO) calculates this figure by multiplying the percentage of people affected by the average duration of a disease and a weighting factor [9]. The weighting factor indicates the health impairment caused by a disease, so it is lower for diabetes, for instance, than for cancer (Fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2. We Live with Disease for Many Years: Years Affected by Disease in Millions. Source: World Health Organization (2017). Includes maternal, perinatal, and nutritional cases.

If we examine the trend, we see a steep increase – by somewhat more than one-quarter since the turn of the millennium – in the number of years in which people are affected by illnesses. In other words, more and more people worldwide are living with a serious disease. Many suffer for years, sometimes unable to work and severely restricted in their daily lives. In 2016, this came to a total of 767 million years of illness worldwide. This trend has been driven by non-infectious chronic illnesses, commonly known as NCDs. The increase in mental illnesses has been particularly strong in recent years. We will discuss NCDs in more detail later in this book.

Length and quality of life don’t always go hand in hand. Just because we more frequently “survive” diseases today doesn’t mean that human suffering has decreased.

This initial examination shows that medical progress has been a success story – people are living longer and longer lives. However, we also live much longer with illnesses, and this often causes a lot of human suffering, for patients and their families alike.

Medical Progress also Means New Challenges

In addition to vaccines and antibiotics, the last 100 years have seen medical advances such as new diagnostic and treatment methods that make it easier to fight disease. Blood tests and imaging methods such as computer tomography, ultrasound, and X-ray help physicians diagnose diseases. Cancer can be treated with radiation, surgery, and chemotherapy, and dialysis machines filter the blood in the event of kidney failure. The list of advancements is long and significant.

But what are the consequences of this progress? We live longer and longer, we live in greater prosperity, and we can more frequently declare victory in the battle against disease. More and more grandparents not only live to see their grandchildren born, but also how they thrive and grow, finish school, get married, and start their own families. In the past, this was the exception rather than the rule. But these gains also bring new challenges.

Economic Consequences

This progress literally comes at a price: it has made medical care more and more expensive in recent years. Treatment-related costs have been rising substantially for years. Take kidney failure, for example: Being diagnosed with kidney failure was once tantamount to a death sentence, but today, with the help of dialysis and kidney transplants, patients can live for many years. In Germany, to name but one example, dialysis treatments cost more than 25,000 euros per patient and year [10]. So where in the past no costs were incurred, today hundreds of thousands of euros are needed. This raises an important question: Who pays the bill?

Historically, it was of course the patients and their families who footed the bill. That was until the beginning of the twentieth century, when health insurance companies began selling policies that let the insured spread the risk, or state-financed healthcare systems distributed the costs among taxpayers. In practice, in most countries today, we find a mix of these three forms of financing.

Because even now, medical costs are not always borne entirely or even mostly by the public or private systems. For many people, illness means economic insecurity. In countries without mandatory universal health insurance, in particular – such as the United States, most African countries, and some Asian nations – falling ill often leads to the loss of hard-earned prosperity gains. While in nations such as Germany or Switzerland people seldom have to dip deep into their personal reserves to treat a serious disease, an estimated 11 million people in Africa fall into the poverty trap every year, because they are forced to rely on credit to cover the costs of medical treatment, which they then are unable to repay [11]. In India, patients pay 62% of all medical expenses out of their own pocket. Which means that many live in fear, not only of the diseas...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Part I Will the Healthcare System Become a Victim of its Own Success?

- Part II Digital Technologies are Changing Patients and Healthcare Systems

- Part III The Five Pillars of the Healthcare System of Tomorrow

- Glossary and Abbreviations

- Bibliography

- Index