- 252 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Techlash and Tech Crisis Communication

About this book

Over the years, tech companies were accustomed to cheerleading coverage of product launches, but in recent years the long tech-press honeymoon ended. It was replaced by a new era of mounting criticism focusing on tech's negative impact on society. This emerging tech backlash is a story of pendulum swings between tech-utopianism and tech-dystopianism. When and why did media coverage shift to corporate misdeeds, and how did tech companies respond?

The Techlash and Tech Crisis Communication provides an in-depth analysis of the evolution of tech journalism and reveals the "inside story" of the Techlash. Furthermore, it shows how Big Tech companies defend themselves from scrutiny by attempting to reduce their responsibility. From employee activism to political pushback, the ramifications are growing.

Until now, the interplay between tech journalism and tech PR has been underexplored. Through analysis of both tech media and corporate crisis response, The Techlash and Tech Crisis Communication examines the roots and characteristics of the Techlash. Insightful observations by tech journalists and tech PR professionals are added to the research data, illuminating the profound changes in the power dynamics between the media and the tech giants they cover. Nirit Weiss-Blatt explores theoretical and practical implications for both tech enthusiasts and critics.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

The Techlash Era

Chapter 2

Big Tech – Big Scandals

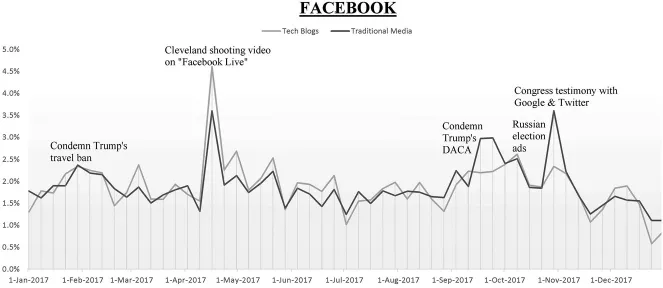

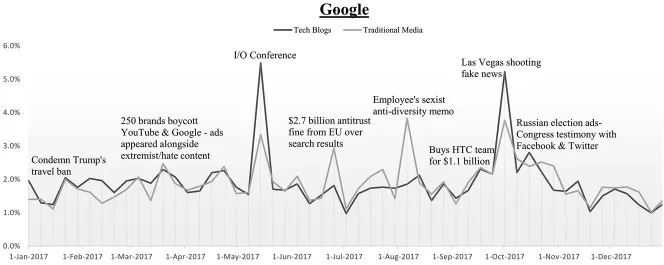

- (1) The Russian election interference (involving mainly Facebook, Google, and Twitter).

- (2) Cases of misinformation/disinformation, extremist content and hate speech, or fake news (e.g., after the Las Vegas shooting).

- (3) Privacy and data security issues, following major cyber-attacks. Examples of data breaches (e.g., Facebook/Uber/Yahoo) represented Big Tech’s data privacy and data protection challenges.

- (4) Allegations of an anti-diversity, sexual harassment, and discrimination culture (e.g., Susan Fowler’s allegations against Uber in February 2017, prior to the #MeToo movement).

The Emerging Techlash Background

Tech’s Biggest Scandals in 2017

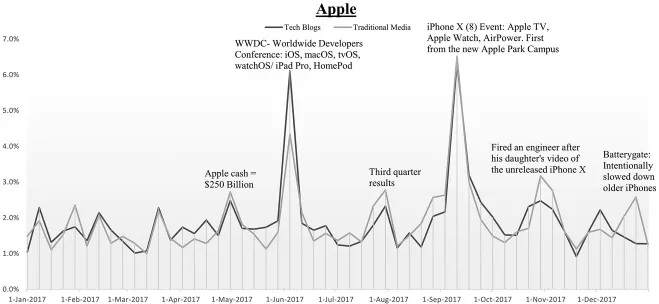

Apple

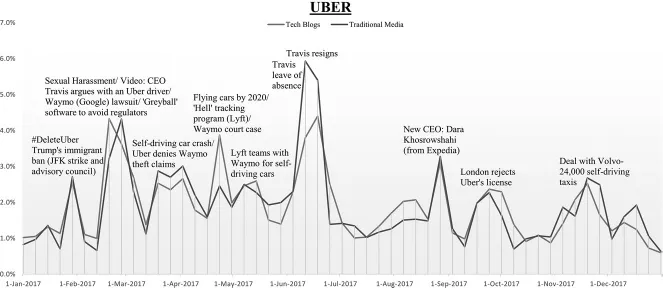

Uber

Title | Short Description |

#DeleteUber – Taxi drivers’ strike | January: People were angered when Uber offered rides to JFK airport during a strike by the union representing NYC taxi drivers, in solidarity with people protesting Trump’s immigration ban. Reportedly, Uber lost around 500,000 customers |

Kalanick stepped down from Trump’s business advisory council | February: Travis Kalanick left Trump’s business advisory council after Uber faced criticism for working with the new administration |

Sexual harassment and discrimination | February: A former Uber engineer, Susan Fowler, alleges a culture of sexual harassment and discrimination. Her post initiated a wave of similar allegations, which later expanded to the #MeToo movement |

Kalanick’s fight with an Uber driver | February: A viral video of Kalanick fighting with an Uber driver. It symbolized that Uber was not listening to the drivers’ concerns |

Waymo lawsuit | February: Waymo (owned by Alphabet) filed a lawsuit alleging Uber used stolen trade secrets regarding autonomous tech12 |

“Greyball” software – fake version to avoid regulators | March: Uber was caught deceiving local law enforcement with a fake version of itself, a software called Greyball, to avoid regulators in regions where it was operating illegally |

“Hell” software – tracking which drivers also work for Lyft | April: Allegations of spying on the rival by using “Hell,” a secret software program Uber reportedly used to track which drivers were working for both Uber and Lyft (to help steer them away) |

Secretly identifying and tagging iPhones | April: Allegations that Uber had been secretly identifying and tagging iPhones even after its app had been deleted and the devices erased. It allegedly stopped only after Tim Cook asked Kalanick to discontinue fingerprinting (or else the app would be removed from the app store for violating Apple’s privacy guidelines) |

More than 20 employees fired, later Travis “resigned” | June 6: More than 20 employees were fired, following the investigation into the workplace culture. June 14: CEO Travis Kalanick took an “indefinite leave of absence.” Eventually (June 21), after investors demanded his departure, Travis “resigned.” |

Twenty years of regular FTC audits | August: The company was hit with 20 years of regular FTC audits, over privacy and data security, after it allegedly failed to protect the information of its users |

Banned from London | September: Uber was banned from London. The transport authority decided not to renew Uber’s license based on concerns about user safety and lack of corporate responsibility |

Covered up a data breach affecting 57... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- The Pre-Techlash Era

- The Techlash Era

- The Post-Techlash Era

- Notes

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app