- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Continuous Change and Communication in Knowledge Management

About this book

Until now, change leadership has lacked a theoretical basis for use by leaders as a starting point when implementing change processes.

This tactical text addresses this. Think of the tightrope walker; they must constantly change the position of their arms and legs to remain 'stable' on the tightrope. Stability depends on change, and change depends on the existence of a stable core. If everything is in a state of flux, the result will be chaos. If everything is stable, the result will be rigid. Rigid systems will collapse if there is the slightest change. Meanwhile, chaotic systems use all their energy to maintain stability.

This book is split into two parts. In the first part, we consider our theoretical basis. In the second part, we describe the leadership tools we have developed for use in change processes. We have designed a leader's toolbox for planned change processes. This toolbox consists of 18 leadership tools. These can be used by any leader to ensure the effective communication and implementation of planned change processes.

Perfect for undergraduate and postgraduate students who wish to expand their knowledge of change leadership focusing on both the theory and the tools needed to implement changes.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

THEORETICAL BASIS

1

COMMUNICATION AND STRATEGIC CHANGE LEADERSHIP

LEARNING OUTCOMES

- Students will gain knowledge and understanding of, and be able to describe, the concept of the ‘ambidextrous organization’.

- Students will gain knowledge and understanding of, and be able to describe, Beer’s Viable System Model.

- Students will gain knowledge of and be able to describe why stability is a necessary precondition for change.

- Students will gain knowledge of and be able to describe the theoretical basis for strategic change leadership.

INTRODUCTION

Analogously, the tightrope walker has to constantly change the position of his/her arms and legs to remain ‘stable’ on the tightrope. The point of this analogy is to show that stability depends on change and also that change depends on the existence of a stable core. If everything is in a state of flux, the result will be chaos. If everything is stable, the result will be rigidity. Rigid systems will collapse if there is the slightest change. Meanwhile, chaotic systems use all their energy to maintain stability. This is the insight that we have built on further to develop our theory of strategic change leadership.

In order to design a stable core that can be used in any change process, both planned and emerging changes, we will integrate Stafford Beer’s Theory of Viable Systems (1979, 1981, 1995), with James G. Miller’s Living Systems Theory (1978), and Russel Ackoff’s thinking about interactive planning and the circular organisation (Ackoff, 1981).

Leaders often experience something that we can call funfair management. This refers to a situation when leaders think they are steering the organisation when they make many decisions (like a child ‘steering’ a car on a funfair roundabout). However, nothing seems to happen further down the ranks of the organisation. The leader sees that there are reefs further out at sea, and wants to steer away from them, but nothing happens in the individual departments, because they have not understood the signals, do not know how to respond to them or because they oppose the changes that are needed.

The worst thing that can happen is that the leader receives confirmatory responses from the various departments, such that he/she believes that his/her decisions have been implemented. However, in reality, no action has been taken. We might also envisage some middle managers working directly against the decision to implement changes. As a result, the ship may flounder on one or many reefs, and everyone becomes a victim of the shipwreck.

The helmsman should have complete control over both the rudder of the boat, the ship’s engine and the crew who are to perform the tasks that will bring the boat safely from one port to another.

Strategic change leadership is defined here as the science of management, control and communication in organisations or the science of effective organisation.1

The leader of an organisation should always have knowledge of the two main systems in the organisation, that is, the information system and the production system. This applies both to classical industrial enterprises and to knowledge and service-producing organisations. We know what is the production system in an organisation by asking the question: What is the system designed to do? or What is the purpose of the system? (Beer, 1979, 1981, 1995).

The answer to these questions will tell us what are the actual tasks of the system and what it is meant to do. If the organisation mainly does other things than what it is intended to do, we have a problem. Either we need to reorganise the system, or we must reformulate the original purpose of the organisation.

In the ship analogy above, the helmsman should have an overview of the following information systems and should at all times be able to retrieve information from:

- The telegraphist and radio. The main task is to receive and send information to and from the ship.

- Communications officer. The main task is to keep an eye on various instruments, such as the radar, and to keep the helmsman up to date on changes in procedures.

- Log books. The main purpose of these is to serve as the memory for the system, so that the helmsman can at all times retrieve information in relation to events on previous trips, courses, ocean currents, etc.

- decisions and must be consulted when the helmsman’s competence is insufficient. The captain also has contact with other systems on land as his main task.

The above information systems may be found in all kinds of organisations. First, someone has the primary responsibility for information exchange with the surroundings. Second, another person has the daily responsibility for internal and external communication. Third, someone must ensure that the organisation’s information is stored in such a way that it is easy to access. Finally, there is always a supreme decision-making unit or person in an organisation, no matter how the system is organised and structured.

Imagine that we are on a large ship, and the ship encounters a storm. We alter course in order to mitigate the effects of the wind on the ship. If the helmsman does not have the instruments necessary to establish the current position compared to the original position, it does not help much that the destination was ever so carefully plotted. The example reflects much of what is happening in organisations today, where the global winds of change are blowing at storm strength. The ‘destination’ (goal) may be clear and well-defined, but the enormous turbulence that surrounds the organisation means that its leaders may not know their ‘ship’s position in relation to its intended course. In addition, today’s organisations are encountering not only increased turbulence, but they must also deal with more complex surroundings. Both these factors – increased turbulence and increased complexity – require organisations to have organisational instruments that can either return the system to its original course or set a new one.

Strategic change leadership is based on four main principles (Beer, 1995; Miller, 1978).

First, the systems of an organisation must have the ability to capture and detect important changes in the environment.

Second, they must be able to relate this information to the standards and values that govern the systems.

Third, they must be able to detect significant deviations from the normal state.

Fourth, communication and control systems must be able to implement corrective measures in behaviour when deviations are detected.

In this chapter, we will explore the following question: How can we design an ambidextrous organisation that can be applied in strategic change leadership?

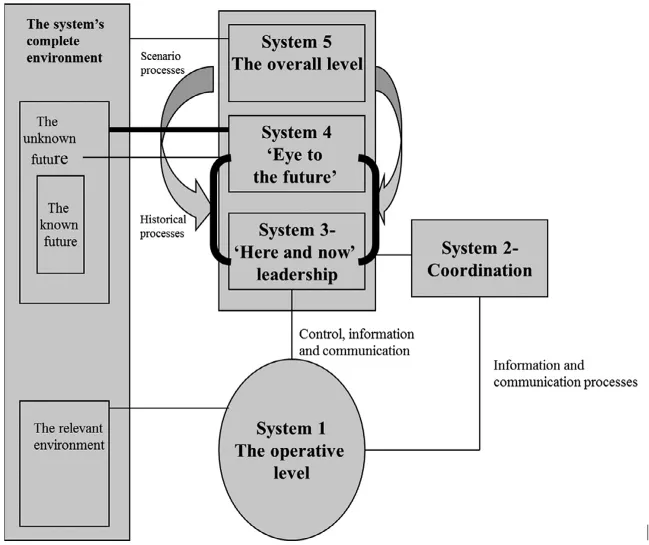

An overall model of the various subsystems in relation to strategic change leadership is shown in Fig. 1. In the introduction, by way of analogy, we used the metaphor of the steering, control and communication on a ship in an attempt to explain the five elements of the model, that is, the various subsystems.

Fig. 1 The Various Subsystems in Relation to Strategic Change Leadership.

This chapter is organised in the following way: First, we explain what is meant by an ambidextrous organisation. Second, we examine each of the elements in the figure.

WHAT IS AN AMBIDEXTROUS ORGANISATION?

Traditionally, organisational structures have only to a limited extent focussed on the co-existence of operational management (exploiting ‘the now’) and innovation (exploring ‘the new’) (Maier, 2015). Although projects have certainly been initiated with this idea in mind, this work has been little institutionalised and has generally been too constrained by existing structures. This was noted by Tushman and O’Reilley as early as 1996. The concept of an ambidextrous organisation was first applied by Duncan (1976). However, it is March (1991) who has been credited with developing the concepts of ‘exploring’ and ‘exploiting’, which correspond with what is meant by ambidextrous organisation. The unique characteristic of an ambidextrous organisation is its ability to adapt to changes in external conditions while at the same time generating its own future by means of, among other things, improved performance, growth and innovation. Ackoff (1981) developed a method whereby organisations could simultaneously adapt to current conditions and create their own futures.

Ambidextrous organisation may be understood in at least three ways. The first perspective is linked to the development of two structures, one focussed on exploiting and the other on exploring the new (Adler, Goldoftas, & Levine, 1999; Nadler & Tushman, 1997; Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996). The second perspective is known as contextual. This perspective applies behavioural and social mechanisms in an effort to integrate, at an organisational level, the exploration of the new and the exploitation of existing resources (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004; McCarthy & Gordon, 2011). A third perspective is an increasing focus on the role of management at both team and organisational levels in ensuring organisational ambidexterity (Cao, Simsek, & Zhang, 2010; Jansen et al., 2006; Rosing, Frese, & Bausch, 2011). This third perspective was also highlighted in 2004 by O’Reilly & Tushman as one of the major challenges for management.

After studying how 85 companies structured their innovation efforts, O’Reilly and Tushman (2004) found that an ambidextrous structure resulted in the best performance within existing operations and was the most successful in promoting innovation. An ambidextrous structure means an organisation is able to manage the leadership and control of daily operations, on the one hand, but also that opportunities to explore new ideas are encouraged and given autonomy, on the other hand.

Of the 85 businesses examined in the research project, some opted for a functional design, with project teams integrated into existing organisational structures. Others employed cross-functional teams, with team members operating within the established organisational structure but outside the existing management hierarchy. Yet others formed unsupported teams that operated outside existing organisational and management hierarchies. And others opted for an ambidextrous structure, with project teams that were autonomous yet still operated within the framework of the company as a whole. All of these teams had their own processes, structures and cultures.

The findings of O’Reilly and Tushman (2004) were overwhelming. Regarding the launching of radical innovations, they found that none of the cross-functional or unsupported teams and only a quarter of the teams with functional designs were able to produce radical innovations. However, among the ambidextrous organisations, 90% were successful in producing radical innovations. Empirical research has shown that this type of organisational design is best for producing both incremental and radical innovations (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004; Thota & Munir, 2011).

An ambidextrous organisational structure has also been found to have other benefits in addition to producing successful innovation. Organisations with an am...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Part I. Theoretical Basis

- Part II. Leadership tools as communication

- Chapter on concepts

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Continuous Change and Communication in Knowledge Management by Jon-Arild Johannessen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Communication. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.