eBook - ePub

Creating Shared Value to get Social License to Operate in the Extractive Industry

A Framework for Managing and Achieving the Social License to Operate

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Creating Shared Value to get Social License to Operate in the Extractive Industry

A Framework for Managing and Achieving the Social License to Operate

About this book

No matter how hard employees work, an organization is in real trouble if strategic decisions are not made effectively. Doing the right things (effectiveness) is more important than doing things right (efficiency). Creating Shared Value to get Social License to Operate in the Extractive Industry showcases concepts and tools to make strategic decisions that determine the future direction and competitive position of extractive company enterprises to create shared value to earn SLO.

Exploring a challenging and exciting keystone topic, Creating Shared Value to get Social License to Operate in the Extractive Industry presents techniques and models that will enable you to actually formulate, implement, and evaluate strategies to shared value to earn SLO.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Creating Shared Value to get Social License to Operate in the Extractive Industry by Cesar Saenz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

SHARED VALUE CREATION TO EARN SOCIAL LICENSE TO OPERATE

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

(1)Explain the need of the shared value creation to earn social license to operate (SLO)

(2)Define shared value creation

(3)Define SLO

(4)Describe the strategic management of shared value creation to get SLO

1.1 Why Do the Extractive Projects Need to Earn Social License to Operate?

The extractive industry has been repeatedly confronted with the dissatisfaction of local, national, and international civil societies with the social and ecological consequences of their operations, especially since the emergence of social and environmental movements in the 1960s and 1970s (Bandler, 1987; Colvin, Witt, & Lacey, 2015; Hall, Taplin, & Goldstein, 2010; Hutchins & Lester, 2006). At this time, growing local opposition to resource extraction projects forced corporations to change their approach toward community stakeholders in order to guarantee smooth operations and access to local resources (Bice & Moffat, 2014; Hilson, 2012; Owen & Kemp, 2012; Parsons, Lacey, & Moffat, 2014; Prno, 2013; Sing, 2015).

Communities are becoming more active in challenging the nature and fairness of the costs and benefits associated with extractive industry developments (International Council on Mining and Metals) (ICMM, 2012).

SLO represents the dynamic of the relationship among the company and communities, government, and society (Lacey, Parsons, & Moffat, 2012). These social actors are people who are near the extractive operations, as well as people who are far away from mining sites, but felt that the overall operations impact them (Graafland, 2002). That is why Brown and Extractive companies must take into consideration the change in community's expectation if companies want to succeed and get the social license.

Nowadays, the legal permission in not enough to start an extractive operation, because residents want to be heard, informed, and considered previously (Bridge, 2004). People who feel that they are impacted by the extractive operations are demanding greater share of benefits from the extraction projects, more participation in the decision-making process, being informed of social and environmental impacts, and be part of the development (Prno and Slocombe 2012).

Instances of extractive developments being delayed, interrupted, and even shut down due to public opposition have been extensively documented (Browne, Stehlik, & Buckley, 2011; Davis & Franks, 2011; Prno and Slocombe, 2012; Thomson & Boutilier, 2011). Likewise, there is now a recognized need for extractive developers to create shared value to get social license to operate (SLO) in order to avoid potentially costly conflict and exposure to business risks (Prno, 2013). There is now a recognized need for developers to create shared value to gain an additional SLO to avoid potentially costly conflict and exposure to business risks (Bridge, 2004).

1.2 Creating Shared Value

Shared value creation is a term coined by Porter and Kramer (2011) who note that companies can create value not only for them but also for society. There are three ways to create value: reconceiving product and market, redefining the productivity in the value chain, and enabling local cluster development.

Reconceiving product and markets: In the case of the extractive industry, the product is the extractive project (mining, oil and energy, forest, and so on) which represents for different stakeholders an opportunity for development and, on the other side, damage, impacts, and unfair development for locals. For this reason, an extractive project must create an attractive proposal not only for investors but also for communities to get SLO. This proposal must not only consider mitigation strategies to reduce environmental impacts but also create economic development in the short and long terms. In this book, different strategies to cope with social issues and to create value for communities to get SLO are presented.

Redefining the productivity in the value chain: It is important to consider all the stages of the value chain of the extractive company to create some measures to mitigate social and environmental impacts; for example, in the transportation of the raw material or products, the company can replace petroleum to gas natural to reduce greenhouses gas emission, or in the distribution stage, the company can transport bigger lots of product instead of small quantity to reduce fleets and traffic.

Enabling local cluster development: The extractive company must consider the creation of direct and indirect employment. The direct employment should be local employment; however, in general, people near to the operation site do not have the skills and abilities to fill positions in the extractive project. That is why companies have to think in the short and long term to train people and build capacities for the construction and the operation stages. The indirect employment could be created by suppliers who supply raw material to the extractive industry; however, it also represents a low rate of employment. The real challenge for the extractive industry is to innovate new ways of economic development and consider the creation of no mining-related activities such as tourism, agriculture, and other diversifying economic activities.

All of theses previous activities allow the company to create shared value which is the best way to show residents around the extractive project and beyond project's sphere of influence that the company is interested in the community development. Shared value creation must be a priority activity for a project in order to get SLO.

1.3 Social License to Operate

The concept of SLO was coined in the late 1990s by a Canadian mining executive, Jim Cooney, and received increasing attention from industry practitioners shortly thereafter. Also, the term emerged in response to a perceived threat to the industry's legitimacy as a result of environmental disasters in the late 1990s (Thomson & Boutilier, 2011).

A social license exists when an extractive project is seen as having the broad, ongoing approval and acceptance of society to conduct its activities (Joyce & Thomson, 2000; Thomson & Boutilier, 2011). According to Corvellec (2007, p. 138), “organizations cannot run their operations unless the communities in which they operate accept their presence.”

Moffat, Lacey, Zhang, and Leipold (2016) note that “these shifts in societal values and their impacts on industry are not unique to the mining sector. Since the term was first coined in 1997 (Thomson & Boutilier, 2011), SLO has increasingly been adopted and applied in a range of other industry contexts to describe the changing nature of company–community interactions and the level of acceptance afforded to resource development operations. This includes the adoption of SLO in various energy industries (Boutilier & Black, 2013; Hall, Lacey, Carr-Cornish, & Dowd, 2015), in farming and agriculture (Shepheard & Martin, 2008; Williams & Martin, 2011), and in forestry (Edwards & Lacey, 2014; Gale, 2012; Wang, 2005) as well as the associated pulp- and paper-manufacturing sector (Gunningham, Kagan, & Thornton, 2004). Within the forest sector, there is evidence that the forest industry in North America started using SLO as early as 1999 to describe their projects and the nature of stakeholder relationships in and around their industry (Cashore, Auld, & Newsom, 2004). However, it was also apparent that very early on in the uptake of the term, it was being used far more extensively by industry stakeholders and there were relatively few instances of it being used or reported in the academic literature.”

1.3.1 SLO Definition

SLO is an ongoing reaching of a community development agreement for ensuring that local communities benefit from investment projects, and the company could continue operation.

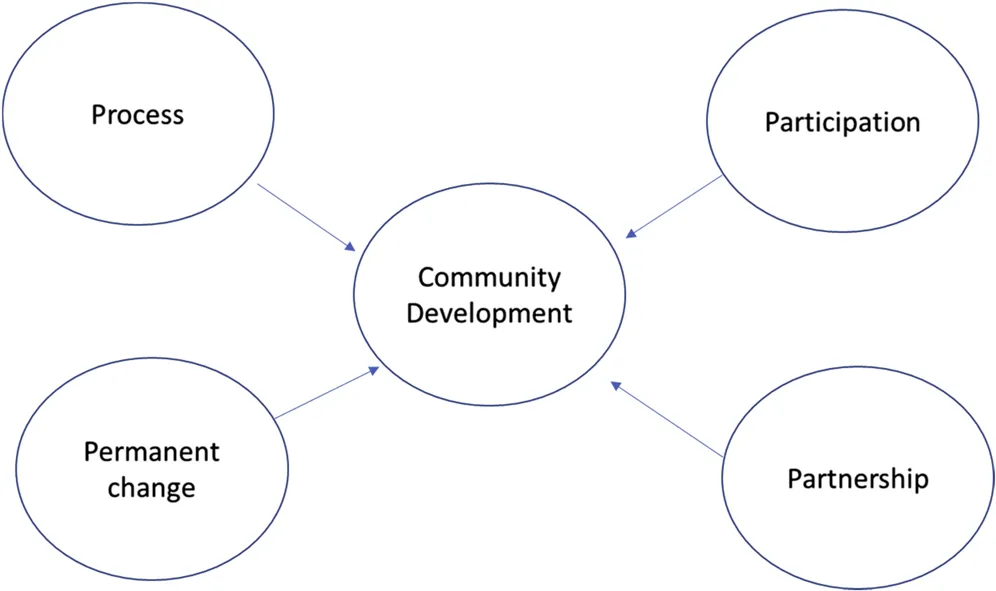

To get the approval of a project, the company has to use the 4Ps of SLO which refers to the set of actions, or tactics, that a company uses to achieve community development. The 4Ps are participation, process, partnership, and permanent change. See Fig. 1.1.

Fig. 1.1. Community Development Qualities: 4Ps.

1.3.1.1 Community Development

Community development is the process of increasing the strength and effectiveness of communities, for the betterment people's quality of life and their participation in the decision-making that will achieve greater long-term control over their lives. It goes beyond mitigating social impacts and focuses on strengthening community viability. It essentially works towards creating local benefits for people that beyond the lifetime of the mining operation. (ICMM, 2020a)

The purpose of SLO is to encourage multi-stakeholder development-focused partnerships. It makes explicit companies' commitment to actively support or help develop such partnerships at global, national and community levels.

Helping to ensure that the companies' investments enhance social and economic development locally and nationally is an important part of accomplishing this purpose.

1.3.1.2 Participation

Ensuring that communities are enabled to participate fully in the decisions made about the allocation of benefits that flow from projects will offer the best chance for community development program sustainability. This will be achieved by concerted stakeholder engagement activities that demystify the extractive project process, empowering community members to understand the motivations as well as project plans of the companies so that they can make informed choices. (ICMM, 2020b)

The right of indigenous peoples and other affected parties “to participate in dec...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- About the Author

- Preface

- 1. Shared Value Creation to Earn Social License to Operate

- 2. A Meta Model of Social Conflict Analysis

- 3. The Internal and External Assessment

- 4. The Creation of Shared Value Based on Good Company–Community Relationships

- 5. Building Legitimacy and Trust to Create Shared Value

- 6. The Extractive Game Triangle Model: Do We Need to Change the Mining Game for Development?

- 7. Implementation of Shared Value Creation to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals

- Index