eBook - ePub

Children of Poverty

Research, Health, and Policy Issues

- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Children of Poverty

Research, Health, and Policy Issues

About this book

A collection of the Proceedings of a Society for Research in Child Development Round Table, held in 1993 by the Society for Research in Child Development (SRCD).The intent of the round tables was "to help chart the course for child development research, health care, and public policy for the next ten years". The contributors believe the papers presented and the round table discussions, along with their broader distribution in this volume, do indeed offer useful insights and powerful guidance to researchers, policy makers, and practitioners and interventionists with a vast range of professional training.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Children of Poverty by Barry S. Zuckerman, Hiram E. Fitzgerald, Barry M. Lester, Barry S. Zuckerman,Hiram E. Fitzgerald,Barry M. Lester in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Research Agenda

CHAPTER 1

Toward an Understanding of the Effects of Poverty upon Children

Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, Pamela Klebanov, Fong-ruey Liaw, and Greg Duncan

Living in poverty exacts a toll on children and families. Research on the dimensions of the untoward effects of poverty is accumulating at a rapid pace, as witnessed by several edited volumes, notably Children in poverty (Huston, 1991), Escape from poverty: What makes a difference for children? (Chase-Lansdale & Brooks-Gunn, in press), and Effect of Neighborhoods upon Children and Families (Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, & Aber, in press), as well as special journal issues of Child Development (Huston, Garcia-Coll, & McLoyd 1993, in press), Journal of Clinical Child Psychology (Culbertson, in press), American Behavioral Scientist (1991), and Children and Youth Services Review (Danziger & Danziger, in press).

Current work tells us that we need to be concerned about poor children and their families. However, it does not inform us as to either the pathways by which poverty exerts its effects on children or on the relative importance of various dimensions of poverty in influencing children.

In this manuscript, we first look at how poverty is measured and how various measurement schemes alter interpretations of poverty effects. Absolute and relative indices of poverty are discussed; then, several recent attempts to use basic needs budgeting as a means to construct the income necessary to insure minimum levels of well-being are reviewed.

Next, we consider how various dimensions of poverty and income influence children’s well-being. Our premise is that the multiple dimensions of poverty are rarely considered, rendering it difficult to provide much understanding of how poverty effects children. Both family and neighborhood poverty are considered in this chapter. Examples are given based on data from two sets of large longitudinal studies—the Infant Health and Development Program (IHDP)1 and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID).2

Then, possible pathways through which poverty might exert effects on children are presented. The first set of pathways focuses on models derived from more macro-oriented disciplines—sociology, demography, epidemiology, and economics. Parental resources, including time, income, and emotional, cognitive, and social capital, are often the constructs underlying this work. The second set of pathways is derived from more micro-oriented approaches, those typically encountered in developmental psychology, psychiatry, and pediatrics. Risk and protective models are often used in developmental approaches. Several examples of additive risk, cumulative risk and double jeopardy models are presented, to see how family processes and risk factors play out in the context of poverty. A brief section considers a more complete model, attempting to marry the different disciplinary approaches (Brooks-Gunn, Phelps, & Elder, 1991; Duncan, 1991). This model is presented in more detail elsewhere (Brooks-Gunn, in press a).

What Is Poverty?

Official Poverty Threshold

The official poverty level is established by the federal government. It is based on the estimated cost of an “economy food budget” or shopping cart of food, multiplied by three. The multiplier was based on the premise that food accounted for about one-third of a family’s after-tax income (Orshansky, 1965; Fisher, 1992). The poverty level is adjusted for family size, the age of the head of the household, and the number of children under age 18. Annual adjustments to the poverty index are made for the cost of living based on the Consumer Price Index. In 1991, U.S. poverty thresholds for families of three, four, and five persons were $10,860, $13,924, and $16,460, respectively. These thresholds are based on incomes before taxes.

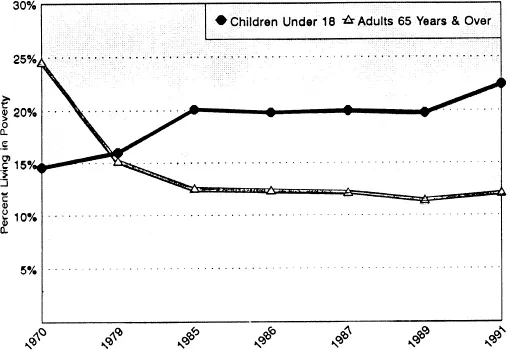

One of the advantages of an absolute poverty level such as the U.S. thresholds is that comparisons may be made on an annual basis. Estimates of the number of persons living below the poverty threshold have been made yearly since 1959 by the U.S. Bureau of the Census (Hernandez, 1993). The comparative usefulness of the poverty threshold is illustrated in Figure 1, which presents the percentage of elderly persons and children in poverty for the past 20 years. As can be seen rates of poverty for the elderly have declined over the time period. In contrast, poverty rates for children have increased during this time period (although rates dropped between 1959 and 1969, not shown in Figure 1). Rates were in the mid-teens during the 1970s, and then rose to about 20% in the 1980s. The percentage of children who were poor continues to be 20% or even higher in the 1990s (currently 23%).

Source: U. S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, Series P-60, No. 168.

FIGURE 1. Percentage of Elderly and Children in Poverty over the Past 20 Years

Much has been written about the causes of the increases in poverty rates for children; causes include (a) structural changes in the economy, including reduction of unskilled and semi-skilled jobs, stagnation of the economy (unemployment rates and wage rates), movement of jobs from inner cities, (b) changes in federal programs, including the failure of government benefits for poor people (e.g. AFDC) to keep up with inflation (eroding the impact of income transfers on families and on the movement of families above the poverty line), and increases in inequalities between the affluent and the poor (in part due to tax changes), and (c) structural changes in the family (increases in childbearing outside of marriage, increases in single parent households due to divorce, increases in maternal employment without the assurance of adequate child care). See Brooks-Gunn and Maritato (in press); Danziger and Stern (1990); Danziger and Weinberg (1986); Duncan (1991); Ellwood (1988); Garfinkel and McLanahan (1986); Hernandez (1993); Palmer, Smeeding, and Torrey (1988); Wilson (1987).

Poverty as a Relative rather than an Absolute Concept

As just stated, the United States uses an absolute standard of poverty, based on what is believed to be necessary for a family’s basic needs (or was believed to be necessary in 1959). While this measure is adjusted for the cost of living, it is based on a standard, which allows for comparisons over time as to how many individuals are poor or not poor.

Relative measures of poverty are not based on a standard. Instead, they are relative to the entire population’s income, and as such change over time. The argument for relative measures has to do with the fact that minimum standards, as viewed by the society, are not static. As incomes rise, standards may also rise. Rainwater (1974, 1992) has presented data pursuant to this line of reasoning very persuasively. For example, public opinion polls from the 1930s through the 1960s have asked questions about how much income families need to “get along” and what income level is low or inadequate. Generally, these polls indicate that about 50% of the median for family income is defined by the population as necessary for basic needs.

Some countries, such as Canada, define poverty relative to the median income of the population. Using such a definition, in the United States, the “absolute” poverty line was .46 of the median income in 1965, and it was .41 of the median income in 1983 (Duncan, 1991; Huston, 1991). Clearly, the number of families categorized as poor would be higher if we used a relative standard such as Canada does.

In a recent volume by Hernandez of the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1993), relative poverty rates were calculated based on having less than 50% of the median family income for each year, following the work of Rainwater (1974). Relative poverty rates are about 37% higher than the official poverty rates for children.

Poverty Rates and Federal Programs

Another indicator of poverty involves the needs standards set for eligibility for various federal programs. Typically, families are eligible for programs if their family incomes are 150% or 185% of the poverty threshold for their family size (eligibility criteria vary by program). If children who live in families within 150% of the poverty threshold are included as poor (often the group between 100% and 150% is labeled “near poor”), the percentage of children age six and younger who would be classified as poor would be over 40%, not just over 20% (National Center for Children in Poverty, 1991).

Basic Need Budgets

The food basket approach to defining poverty thresholds, while easy to understand, is limited. Reasons include the following—food today accounts for about one-fifth of a family’s expenditures (housing costs having increased substantially since 1959), the official poverty level only includes cash income (excluding in-kind transfers such as food stamps and medical care), and the current level does not take into account regional variation in living costs (with housing and transportation being two costs that vary greatly).

The food basket approach estimates what a family requires to meet its basic needs (by using a multiplier). Recently, several economists have built basic needs budgets in a slightly different way than Orshansky did (Ruggles, 1990; Watts, 1993). Watts terms the food basket approach the gross-up approach and the basic needs budget approach the category standard approach. Expenditure norms are derived for a small number of categories, usually food, housing, transportation for employed adults, health care, child and dependent care, clothing and clothing maintenance, personal care and miscellaneous. The budgets are, as Watts says, lean. They do not include what developmental psychologists would call learning or stimulating experiences (no books or other reading material, no recreation, no educational expenses). They do not take into account the cost of obtaining quality child care or moving to neighborhoods with high quality schools. They do not include what we might call “start up” costs (furnishing an apartment). Even so, in the Ruggles (1990) calculation, the number of single parent families living below the poverty line in 1989 would be 39% using the official poverty threshold and 47% using their basic needs budget (rates for children would be 48% vs. 56%).

It is clear that there is no consensus as to whether the poverty level should be determined by a method other than the food basket by three method, whether it should be adjusted for regional variations in cost of living, whether it should be based on expenditures, rather than income, or whether it should include in-kind transfers. However, this brief discussion does illustrate the difficulty that today’s family at the poverty line or slightly above it has in making ends meet.

Life below the Poverty Threshold

We have still not confronted what it means to live below the poverty threshold. First, it is clear that individuals below the poverty line cannot meet basic expenses. Our colleague, Ann Doucette-Gates, has provided an estimate of basic income needs for a family of four in New York City. She includes housing (rent), food, basic needs, and taxes. Estimates of income are made for a family on AFDC, a family where one individual works a 40-hour week at minimum wage ($4.25 an hour), and a family where one individual works a 40-hour week at $10 an hour. The family with an employed adult is below the poverty line, as is the family on AFDC. These two families bring in over $350 less than what their basic expenditures are (not including health care and child care costs). The family where the wage earner brings home $10 an hour just about breaks even.

The poverty threshold makes no distinction between receipt of income from AFDC, from employment, or from both. Debates centering on the possible existence of a welfare culture and on the inadvisability of requiring poor mothers to enter the work force would benefit from such information (Smith, in press; Zill et al., in press; Wilson, Ellwood, & Brooks-Gunn, in press). It also makes no distinction between families who are close to the poverty threshold and those who are way below it.3

Estimates of effects of poverty upon children are often made looking at income, rather than focusing on “a” poverty line. However, unless non-linear models are employed to see if income effects are more pronounced at the bottom of the income distribution or if a disjuncture in income ef...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Contributors

- Part One: Research Agenda

- Part Two: Health Care Agenda

- Part Three: Public Policy Agenda

- Author Index

- Subject Index